Maldives, hailed as democracy poster child, turns to Islamist fundamentalism

Loading...

| New Delhi

The Maldives, long known as a tropical paradise destination for the rich and famous and held up as a democracy good news story, has recently taken a democratic nosedive, says its ousted president who is now looking for international help.

Mohamed Nasheed ushered in what he termed the “dawn of democracy” when he was elected president in the Maldives’ first multiparty elections in 2008. After three years in power, he says he was forced to resign by an angry mob of police officers and soldiers. The coup, he says, was engineered by his autocratic predecessor, Maumoon Abdul Gayoom, who served as president from 1978 until 2008.

Mr. Nasheed has expressed his dismay at India’s recognition of the new president, Waheed Manik, and says he is concerned that the current Maldivian government is a catalyst for conservative Islamist groups to take a deeper hold on society.

He points to the 2008 presidential race: The main Islamist political party did not perform well then, and in subsequent parliamentary and local cabinet elections it did not win a single seat. But after the coup, the new government gave the Islamist Party three seats in the parliament. The parliament is currently composed of 77 members.

“There are radical elements within the military and within the cabinet,” Nasheed says. “This disproportional representation is alarming. These Islamist groups want to have a better hold on society, because they have found an inroad into power through the current government.”

Nasheed says he is now trying to restore democracy by drumming up international support for early elections. The sitting Maldives government announced it would hold elections early, in July 2013, but Nasheed and many analysts are skeptical.

Islamic fundamentalism on the rise

The conservative Saudi Arabian strand of Islam, known as Wahhabism, has been growing in the Maldives for decades.

Nasheed says conservative Islamic groups are already pushing for changes in educational curricula and making moves to stop entertainment, singing, and music. Recently an Islamic Party called on the state television broadcaster to ban the annual televised national singing competition because the group believes the music is against Islamic teachings.

“It is so sad these reforms are happening without the consent of the people and while the people want something else,” he says.

Azra Naseem, a Maldivian woman who studies the radicalization of Muslims, says women are likely to be most affected by the conservative shift.

“The increasing degradation of women, the calls for women to cover up and stay home, to drop out of the labor market, and to engage in anachronistic and often cruel practices, such as female genital mutilation or child marriages. This was not a part of Maldivian life as we knew it only a short decade ago.”

With only one university in the Maldives, and that one recently built, if young people wanted to pursue their education beyond high school they often relied on scholarships from abroad. Many of these scholarships came from private religious schools in places like Saudi Arabia and Pakistan. That was the greatest contributor to the spread of radical Islam in the Maldives, says Dr. Naseem.

“These young Maldivians came back home and began preaching a much more conservative version of Islam. Given the remoteness of the islands, it’s easy for returning preachers and graduates to influence an insulated island population," she says. It was “in defense of this radical and totally un-Maldivian Islam that a large percentage of Maldivians were recruited by Islamists to partake in, or at least support, the overthrow of its first democratically- elected government.”

During his time as president, Nasheed faced a growing backlash from Islamist groups and their supporters who felt his efforts to have diplomatic relations with Israel and his liberal policies were un-Islamic.

“Nasheed’s failure to take action against the rising radical Islamic ideologies in the Maldives was one of his greatest weaknesses, and it ultimately led to his downfall,” says Naseem. “But, instead of taking steps to restrict extremism, the current government is actively encouraging and feeding it.”

Instability in the Maldives

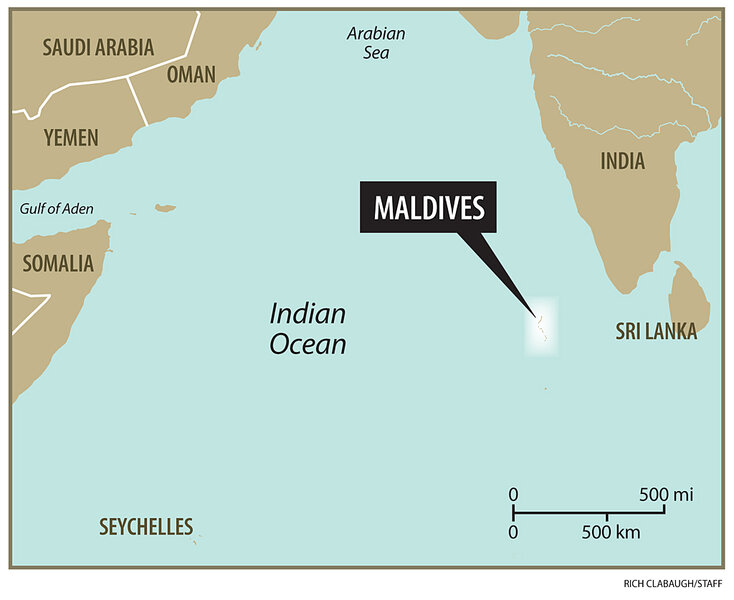

If the Maldives continues in this direction, other countries, such as China, could come and exploit the situation, says retired Maj. Gen. Dipankar Banerjee, the director of the Institute of Peace and Conflict Studies in India. “Given the Maldives strategic location in the Indian Ocean, instability in the region could have a far-reaching impact on geopolitics.”

More than 80 percent of international trade to and from Asia passes through the Maldives. And while India and the Maldives enjoy strong relations, the nation is also of strategic interest to China.

“China’s foremost interest in the Maldives is to protect its increasingly important supplies of energy that need to transit the Indian Ocean,” wrote Anand Kumar, an associate fellow at the Institute for Defense Studies and Analyses, in a paper on Chinese engagement with the Maldives. “China has been trying to engage with the Maldivian military for decades. It knows very well that a base in the Maldives would put the country in control of the oil routes in the region and give it greater dominance over the sea lanes.”

China is already making inroads in the Maldives through infrastructure projects and supporting the tourism industry. It is also becoming one of the most popular business destinations for Maldivian traders.

“When [former President Maumoon Abdul] Gayoom was in power, China enjoyed much warmer relations with the Maldives than with Nasheed’s administration,” says Mr. Kumar. “If there is a change in the balance of power in the Maldives toward China, this would be a disadvantage to the US because their strategic space in the Indian Ocean would shrink.” The US has a military base in Diego Garcia, an island in the Indian Ocean, but it wants to restrict Chinese presence in the Indian Ocean because of its strategic value.

With elections a little more than a year away, the future of the Maldives and the region is still uncertain.

Future Elections

Given the confused nature in which the Maldivian transfer of power took place, India would benefit from an early election held as soon as possible, says Banerjee. “But ultimately that’s up to the Maldivian people.”

Naseem says the international community could play an important role putting pressure on the current Maldivian government to push for elections.

“What we are going through in the Maldives at the moment is an authoritarian reversal at full throttle,” says Naseem. “Democracy is in free fall. The sad thing is, caught up in partisan politics, a large percentage of the Maldivian public remains unaware of the enormity of the loss – it is not merely our first democratically-elected leader that we have lost but democracy itself, and along with it, the right to govern ourselves.”