Indians rally against a boom in corruption

Loading...

| New Delhi

Indians who turned out by the tens of thousands recently to protest corruption are following a pattern seen in other fast-rising economies: Growth spurts are followed by spikes in corruption – until reformers push back.

And resistance has arrived here with surprising force.

Standing with crowds in the muddy Ramlilah fields, the center of anticorruption rallies, government servant Devinder Singh sees stickier fingers around him these days. He blames a keeping-up-with-the-Joneses mentality. "We need many, many things now – mobile phones, good vehicles, a good house," says Mr. Singh. "Corruption actually grows with the demands of the [bribe takers]."

Nearly every protester points to the string of scandals made possible by new wealth, including a rigged auction of a cellphone spectrum that defrauded the country of $40 billion.

"There's not an economy in the world where you have had rapid economic growth and transformation of an economy without a rise – at least for a while – in corruption and inequality," says Vivek Dehejia, an economics professor at Carleton University in Ottawa. "You can say the growth caused the corruption, and in some sense the corruption leads to its own correction. And if you don't do that, you can get stuck and wind up in a middle-income trap," he adds.

Britain's imperial heyday saw the purchasing of Parliament seats in so-called rotten boroughs. Robber barons rose up alongside the US economy, touching off the Progressive Era. Today, other so-called BRIC countries – Brazil, Russia, India, and China – have seen a similar story.

Russian oligarchs ran off with state property during the 1990s transition from communism. In China, last month's bullet-train crash sparked corruption concerns among the middle class.

In China...

"It makes them angry that [officials] build a high-speed rail line and it is flawed, [or they] buy a condo and find that it's poorly built," says Andrew Wedeman, a China expert at University of Nebraska-Lincoln. "They think when incomes go up, quality of life should go up."

China emerged from the Cultural Revolution with a defunct judiciary. In a decade, courts were hearing cases of complex financial corruption, says Dr. Wedeman, author of the forthcoming book "Double Paradox: Rapid Growth and Intensifying Corruption in China."

"They are putting it together on the fly. Essentially, corruption kind of swamped the anticorruption [measures]," he says.

China's ruling party has fought back. Some 10,000 officials are sent to prison each year and some are executed. Wedeman says the efforts have helped contain corruption.

India hit boom times with a broken court system, but the democratic process here has responded slowly. New agencies have been created, but the government has curtailed them, partly to preserve a balance of powers. More than 20 percent of the jobs at the Central Bureau of Investigation, India's corruption watchdog, lie vacant. CBI cases languish in courts, with 23 percent pending for more than a decade.

Demonstrators demand a new agency that would have sweeping authority. Critics worry the movement represents a departure from democracy, with its efforts to override elected lawmakers.

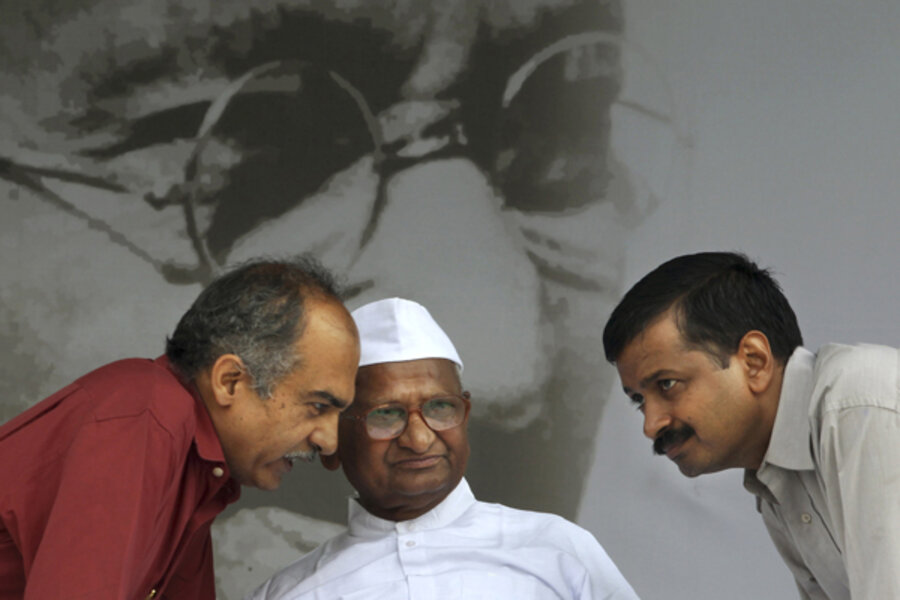

Anna Hazare's role

But, in other ways the movement sounds like the Progressive Era, one of the most famous democratic responses to corruption. The leader of India's street protests, Anna Hazare, also echoes the Progressives' interest in personal purification as a part of the national cleanup.

"It is my good fortune to give my life for my country," Mr. Hazare said at Ramlilah, a week into his protest fast. He called the anticorruption fight India's second freedom struggle. The social activist told how years ago he saved a village by enforcing a liquor ban: "Please do not get into addictive behavior – drinking, smoking."

India's industrial giants – some of the biggest bribe givers – are calling for a corruption crackdown, too. The reason: investors now shunning companies with strong political ties, worried that a sudden scandal could wipe out stock values.

Research by Ambit Capital in Mumbai found that companies reliant on government licenses or other political ties underperformed by 14 percent over the past year. And brokerage firms here are now helping investors understand how reliant companies are on political favors, reports the Mint newspaper.

"Over time, economic growth gives rise to groups in society – media, human rights groups, trade unions, some businesses, and even within the state – who begin to have an interest in controlling corruption," says Jon Moran, a corruption researcher at the University of Leicester in Britain.

Still, says Professor Dehejia, "It's not that we should be OK with massive corruption because we can just shrug our shoulders and say we've all had to go through it.... We should be concerned and there should be policy programs. But [let's not] start wringing our hands."