Follow the money: Should the US cut aid to Pakistan?

Loading...

| New Delhi; and Islamabad, Pakistan

Americans and Pakistanis are putting pressure on their governments to downgrade bilateral relations following the US raid that killed Osama bin Laden.

At Pakistan's request, the US is pulling out some of its soldiers from the country. With only 200 soldiers on the ground, the cuts are mostly a symbolic effort aimed at easing Pakistani frustration. Today, US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton stepped in to calm tensions by announcing the US wants "long-term" security ties with Pakistan.

Meanwhile, responding to popular American anger, Congress is threatening substantial cuts to US aid and Pakistani populists are saying good riddance. Beyond the angry rhetoric on aid, experts see a mismatch between US hopes and where the dollars have gone.

How much US money is in Pakistan?

The US has provided $20.7 billion to Pakistan since 2002. A little more than two-thirds of that went to military use, the remainder to civilian.

The biggest ticket item, at $8.9 billion, is something called "Coalition Support Funds." These are reimbursements for Pakistan's military assistance in the war on terror.

The second-largest chunk, $4.8 billion, falls under "Economic Support Funds." Most of this has gone to shore up the government's budget, either as revenue or to pay off debt to the US.

Much less is spent on seemingly major US priorities: The Frontier Corps, the Pakistani force doing most of the fighting, has received $100 million. Antiterrorism and nuclear nonproliferation efforts: $90 million.

"One of the things we should be doing is training the police, but we're not doing it.... Pakistanis are not letting us. They want the Army to do everything," says C. Christine Fair, assistant professor at Georgetown University in Washington.

What has Pakistan's Army done with the money?

The short answer is: No one quite seems to know. The US reimburses Pakistan for costs associated with the numerous military operations launched following US goading.

But the Defense Department has failed to obtain enough information to judge whether $2 billion in claims were valid, according to the Government Accountability Office. Their 2008 report found evidence of double billing or repayment for unrelated or nonexistent efforts, including $200 million for radar upgrades – even though militants have no air force that would require such radar.

Former President Pervez Musharraf later confirmed suspicions that aid had been diverted to defend against India. "Whoever wishes to be angry, let them be angry," he said in 2009. "The Americans should know … that we won't compromise our security, and will use the equipment everywhere."

The United States has gotten tougher on reimbursements, rejecting 44 percent in 2009, compared with 1.6 percent in 2005, according to The Wall Street Journal.

"Reimbursement claims are reviewed carefully and decisions are based on a combination of agreed formulas," says a US official in Islamabad, via e-mail. "However, we do not control what the government of Pakistan does with reimbursement funds that go into the state bank."

Hasn't the US boosted civilian aid?

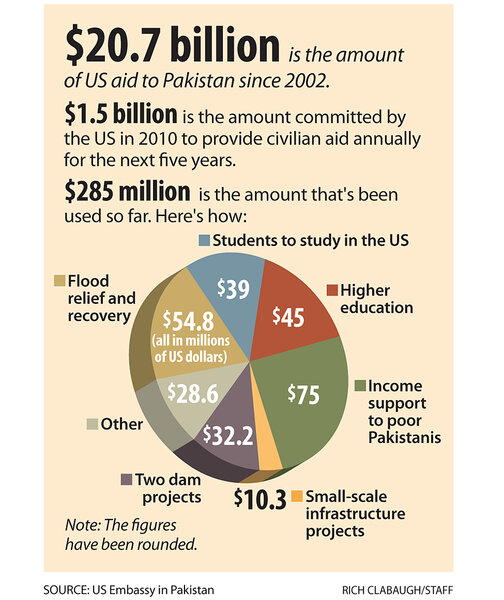

In 2010, the US committed to providing $1.5 billion annually for five years in civilian aid. But only $285 million of this Kerry-Lugar-Berman Act money has been spent so far, according to the US embassy.

Sen. Richard Lugar (R) of Indiana, a cosponsor, chalked it up to difficulties determining which projects to fund and how to account for them.

The sluggishness is partly due to reforms at USAID, says Ms. Fair. After years of complaints that development dollars wound up enriching US companies, the agency moved to channel funds through the Pakistani government and small nongovernmental organizations. "When we moved away from institutional contractors to small NGOs, we are basically moving into an unknown," says Fair.

The US embassy provided a breakdown of how Kerry-Lugar-Berman Act money has been spent. It includes $32.16 million for two dam projects, $54.8 million on flood relief and recovery, $39 million for students to study in the US, $45 million for higher education, $75 million for income support to poor Pakistanis, and $10.34 million for small infrastructure projects.

Such figures are not readily available on the website and take some time for USAID to produce, frustrating those tracking the projects. The lack of transparency worries Pakistanis who often distrust NGOs, says Fair. Previous efforts by the Monitor to observe USAID projects in Pakistan have been met with ambivalence. The agency says it wants to show how the US is helping Pakistan, but it worries about drawing militant attention.

During hearings earlier this month, Sen. John Kerry (D) of Massachusetts said: "We have raised this issue forcefully ... there needs to be a much more effective communications strategy."

What US goals has the money accomplished?

Military aid to Pakistan is aimed at cooperation in the war on terror.

Since 2001, Pakistan has launched offensives against Islamic-militant havens. Pakistani intelligence has helped the US nab some top Al Qaeda leaders. Islamabad has also risked popular discontent by allowing the US to base drones and more CIA operatives on its soil.

Yet the help dries up when it comes to targeting groups most active in fighting the US in Afghanistan. Insurgencies are hard to defeat when they have sanctuary across a border. Meanwhile, Pew Research Center finds that just 11 percent of Pakistanis have a favorable view of the US, up one point from 2002.

"In the past decade, we've seen $14 billion [in] military aid come in, but has militancy changed? If anything, it has become more acute," says Aasim Sajjad Akhtar, a political economy professor at Quaid-i-Azam University in Islamabad.

What if the US cut aid?

US lawmakers have said the most likely targets for cuts would be civilian, not military, aid.

Cutting civilian aid would have only a 0.14 percent impact on Pakistan's GDP growth, calculates Shahid Javed Burki, a former World Bank vice president.

But the real concern for Pakistan's solvency would be loss of support from international lenders such as the World Bank and International Monetary Fund (IMF).

"If the US pulls out of the relationship, the IMF and World Bank look to the US before deciding, and private investors will take a huge hit," says Moeed Yusuf, South Asia adviser at the United States Institute of Peace in Washington. "Pakistan won't fail if aid disappears. But for a country in trouble, do you really want to isolate it?"

In 2008, the economy took a nose dive and the IMF kept it afloat with loans. Pakistan's former representative to the IMF board, Ehtisham Ahmad, said recently that the IMF was going to deny the bailout request until a last-minute intervention by the White House. (The IMF in Pakistan declined to comment.) "As long as the multilateral aid continues, it won't impact Pakistan's economy," says Sartaj Aziz, a former finance minister.

A US official in Islamabad argues that yanking civilian aid would undermine the US message of a long-term commitment to Pakistan. It would also affect the civilian government's ability to provide services, further undermining it.

Rescinding military aid would involve a larger chunk of money, deepening the economic impact to the country. It would also lead to a cancellation of Pakistani military help along the Afghan border.

"Pakistan would say we are pulling out our troops. Handle this border yourself, but don't violate the border," says Imtiaz Gul, a strategic analyst in Islamabad. "I would only hope that better sense would prevail."