Congress brings down top auditor of Afghan corruption. Wrong target?

Loading...

| New Delhi

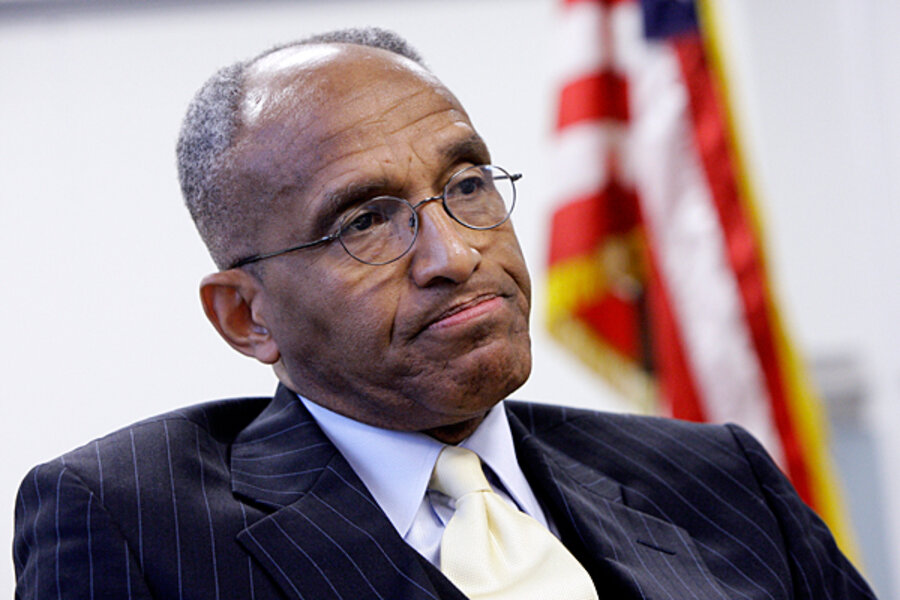

The US government’s top auditor of reconstruction funds in Afghanistan resigned this week, after facing tough Congressional criticism that his agency was not moving aggressively enough to combat fraud and waste.

During Arnold Fields’s 18-month tenure, the Special Investigator General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (SIGAR) completed 34 audits tied to $4.4 billion in reconstruction spending that led to four convictions and the recovery of $7 million of US taxpayer funds.

While a recent peer review uncovered weaknesses within SIGAR, development experts with experience in Afghanistan say that the auditors are not at the root of the problems facing the country’s reconstruction. Instead, many cite the failure of US agencies and other officials to listen to the auditors – including in the halls of Congress.

“The auditing of US government-funded projects is really important, but it’s not the central piece [to help end corruption and waste in Afghanistan]. It’s following up on those findings,” says Ashley Jackson, head of policy for Oxfam International in Afghanistan. “If you look at the audits you see the same problems pointed out time after time.”

SIGAR's findings in Afghanistan

Some of the toughest – and most repeated – SIGAR criticisms of aid projects:

* Poor record-keeping. In 2009, SIGAR found that the US military did not know how many projects it was funding that year because of incomplete databases.

* Shoddy and unsustainable projects. In a forthcoming audit, SIGAR found that half of the military reconstruction projects surveyed already show maintenance problems after handover. A Monitor investigation found similar problems with other US projects, mostly as a result of poor or incomplete construction, as well as unsubstantiated expectations that Aghans could continue supporting a project.

* Cost overruns due to contracting problems. Last year, SIGAR reported that a $125 million contract to build a power plant in Kabul ballooned to $300 million and was a year late. This month, the US government awarded the same firm, Black & Veatch, a $266 million no-bid contract for another Afghan power project.

Criticism of SIGAR from the US Congress

But a bipartisan group of senators on the Subcommittee on Contracting Oversight criticized SIGAR for nearly two years, first for sluggishness in hiring auditors, then for a lack of aggressiveness in the field.

Complaints intensified following peer reviews of SIGAR completed in August that presented a mixed picture of the fledgling agency. The reviews found SIGAR’s strategic plan had no performance targets and that the agency did not conduct formal risk-based assessments to help prioritize which projects to investigate. The report also noted that “stakeholders” were unhappy they weren’t consulted in that prioritization process.

SIGAR began working on implementing the peer review suggestions. But Fields also hired an “independent monitor” to oversee SIGAR’s performance, choosing a former Defense Department Inspector General who resigned in 2005 under allegations of misconduct that included misleading Congress.

Congress wasn’t amused. Sen. Claire McCaskill (D) of Missouri, chairman of the Subcommittee on Contracting Oversight, and committee member Sen. Tom Coburn (R) of Oklahoma wrote President Obama requesting Fields be fired.

Fields's departure

Reacting to Fields’s departure, Senator McCaskill released a statement saying, “Mr. Fields simply was not the right person for this very difficult job. I hope his departure will allow the agency to turn over a new leaf and finally begin to do the important contracting oversight work we so desperately need.”

Ms. Jackson with Ofxam says SIGAR has already done some valuable work, particularly in prying information out of the US Agency for International Development (USAID) and military reconstruction groups known as Provincial Reconstruction Teams (PRTs).

Andrew Wilder, an aid expert at the US Institute for Peace in Washington, says SIGAR has faced a tough task given the poor data available.

“Because of the imperative to spend money quickly, record keeping was very weak, so I’m somewhat sympathetic to those who are trying to conduct audits.” Says Dr. Wilder. “I think it’s gotten better in the last year or two partly because groups like SIGAR have tried to promote [better record-keeping.]”

For Jackson, SIGAR’s work does fall short in comparison to what was accomplished by its companion investigation unit in Iraq, known as SIGIR. The latter’s reports provided a clearer big picture view on reconstruction progress and pitfalls, she says.

And given the repetitive nature of SIGAR’s reports, the ideal leader for the agency would be a more forceful advocate for getting the recommendations implemented, she adds. “[But] this is also the role of Congress. They repeatedly called up Fields to testify … but what is their role in seeing that concrete changes are made?”

At this point, problems such as short tenures for aid workers, a focus on quick results, and poor coordination among the various players in the field are well known. So, too, is the corruption in the Afghan government, a discouraging reality that saps attention from reform efforts on the US side.

Congress's role?

Congress, says Jackson, has responded unhelpfully when its frustration with President Hamid Karzai boils over by issuing “knee-jerk” threats to suspend development dollars.

Wilder agrees that Congress has a role in the mistakes, but from the perspective of throwing too much money into the reconstruction of a country that cannot handle what he calls a “tsunami of cash.”

“I wouldn’t hold the auditors responsible for the corruption in Afghanistan. In addition to those who are actually pocketing the money, I would hold responsible those trying to spend far too much money in a war zone where there is little capacity to implement programs or provide adequate oversight over how funds are spent,” says Wilder.