The rise of India's pulp fiction

Loading...

| New Delhi

Indian novelists have joined the canon of modern literature, earning critical acclaim and topping bestseller lists in New York and London. Writers like Salman Rushdie and Vikram Seth are known for colorful epics that weave Indian history and culture into personal dramas. Each book is a labor of love, a door-stopping tome.

"Stilettos in the Newsroom," on the other hand, has far fewer pretensions.

A slender, slangy story of a female reporter on the make, it is aimed squarely at young, impressionistic Indians who can afford its 95-rupee (about $2) cost. It has sold 20,000 copies since February, according to its author, Rashmi Kumar, a journalist and first-time novelist.

It's one of hundreds of similar English-language novels set in the offices, schools, and homes of India's booming cities. Known as quick-read novels, they tap into the aspirations of young Indians between the ages of 16 and 24, a bulging demographic in a country of more than 1 billion people.

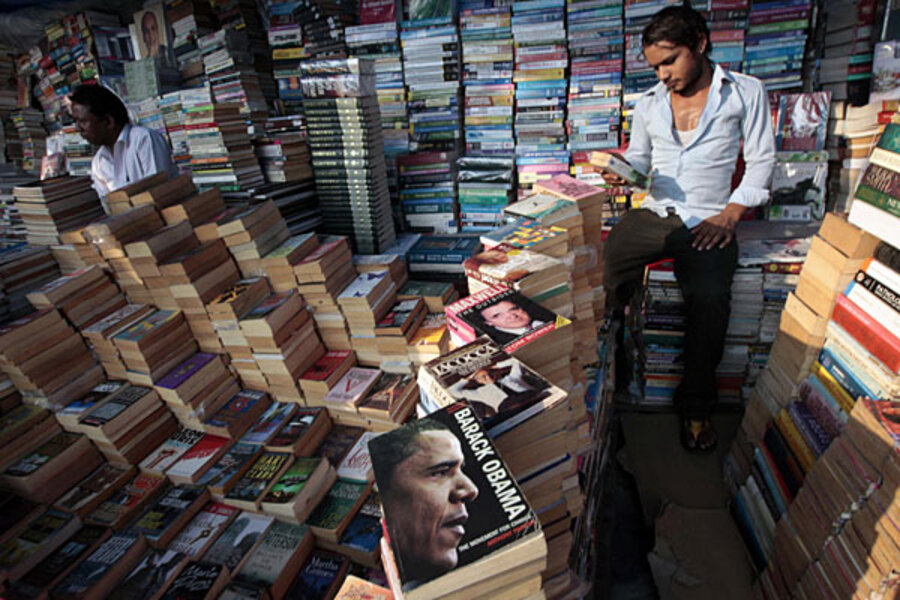

While critics sniff at the sloppy grammar and colloquial prose, booksellers welcome the genre as a relief from epic novels that earn respect but don't move volumes. "It's the only thing that gets us the money," says Anuj Bahri, who runs Bahrisons, a venerable bookstore in Delhi, and also works as a literary agent.

The rise of the quick-read genre

India's dominant booksellers are small shops that don't use computers, making it difficult to compile sales figures. But publishers agree that the quick-read genre is rising exponentially as more Indians learn to read and have more disposable income.

This rise in literacy means that India now has the world's largest circulation of daily newspapers, ahead of China. Books are also popular: A recent survey by the National Book Trust estimated that India has 83 million regular readers between the ages of 13 and 35. Seventy-five percent of those readers read books at least once a week. Their favorite leisure activity, however, was watching TV.

Many trace India's quick-read phenomenon to the success of Chetan Bhagat, an investment banker turned bestselling writer. Since 2004, his four novels have sold millions of copies and three have been made into Bollywood movies, vaulting him onto Time's current list of the world's 100 most influential people.

Kapish Mehra, managing director of Rupa & Co., India's largest publisher of English-language titles, says Mr. Bhagat is wildly popular among young people who rarely read novels because he captures their voice and their viewpoint. Crucially, he uses English as it's spoken in India, spliced with Hindi, brand names, and tech lingo.

"This is the language that young Indians speak. Lots of people relate to it. As publishers, our job is to put out content that people can relate to," says Mr. Mehra, who is himself in his late 20s.

New wave of aspiring writers

As publishers scramble to emulate Bhagat's success, a new wave of aspiring writers has arisen to meet the demand for modern novels. Some publishers act as vanity presses for authors willing to subsidize their debuts, however poorly written. Others are focused on finding the next million-copy sellers from a deluge of scruffy manuscripts.

The result is a boom in new fiction with catchy titles that leaves many critics aghast. "With a few honorable exceptions, the 100-rupee novels aren't just mediocre, but awful," wrote a reviewer in The Mint, a business daily.

Mr. Bahri agrees that the new fiction on his shelves is garbage but says that some real talent may eventually emerge.

"At least we've got a new generation of writers. Indians must go beyond looking for a magnum opus," he says, taking a swipe at India's literary giants.

Ms. Kumar took a six-month sabbatical to write "Stilettos in the Newsroom," a 138-page semiautobiographical account of an ambitious, fun-loving cub reporter. Each chapter concludes with a lesson. "Journalism rule number 5: Office romance can be fun ... only if done with the right people!" In pure comic form, it ends in a wedding.

Kumar is working on a follow-up novel. She says that her style is tailored to her audience and makes no apologies for her prose. "I'm not particularly hoity-toity. I chose not to be like this. I chose to cater to the masses," she says over tea in a Delhi cafe.

Most quick-read novels take place in cities like Mumbai or on elite college campuses, far from the downtrodden villagers that fill the imaginations of other Indian writers. But the books sell well in India's vast hinterland where young readers are avid for contemporary stories, says Jayanthakumar Bose, chief executive officer of Delhi-based Srishti Publishing, which specializes in the genre. "The small cities and the rural market is where the next fight for supremacy [among publishers] will occur," he writes in an e-mail.

Many of Sristi's 47 titles, such as "Pink or Black" and "Of Course I Love You … Till I Find Someone Better," are by first-time writers. "Our philosophy has always been to provide new, budding Indian authors with a platform for telling their story," says Mr. Bose.

International publishers are also tapping India's youth market. British publisher Penguin sells a range of paperbacks at 150 rupees that promise "fun, feisty, fast reads for the reader on the go." Both HarperCollins and Penguin publish "chick lit," Indian titles for female readers.

While English-language novels rarely sell more than 20,000 copies, print runs of Hindi-language novels can reach 200,000, says Bahri.

Still, Kumar, who grew up in Pune and speaks Marathi, says she never considered any other language to tell her story. "As a youngster, we've been taught in English, we express ourselves in English. It is natural and easy," she says.