Americans build elite Afghan commando force

Loading...

| Rish Khvor, Afghanistan

Pvt. Said Reza says he's ready to be a soldier in his country's fight against extremists, and as he stands in uniform in the middle of a training camp here with his semiautomatic rifle, kneepads, and American-style dark glasses, he looks the part.

Private Reza has already graduated from basic soldier training. He volunteered to become a member of an elite unit of the Army that is being groomed to become a model force of Afghan warriors.

"The only thing I know is that these [extremists] are a bunch of people who sell their country for a very small amount of money," says Reza of the extremists he expects to fight. When asked if he's ready to take them on, his answer is simple: "Bali ho" – of course.

Trained to be "the best of the best," who fight in riskier, more complex political and military environments – say, taking on a popular tribal leader aligned with the Taliban – the Commandos are distinct from the regular Army but are expected to help define the image and capabilities of Afghan security forces as a whole. The goal is an elite, quick-reaction force that can act independently. It's a crucial addition for an uneven US-NATO mission that many military and civilian leaders agree has evolved in a way that has let the Taliban resurface.

But here at this former Soviet training base in the town of Rish Khvor, near Kabul, the company of US Army Special Forces Command in Afghanistan, 3rd Special Forces Group that is training this band of men is in no danger of putting itself out of a job. With training that gives them a leg up from the common Afghan soldier, these Afghans have helped US forces to nab 40 of the most wanted extremist leaders since last year.

But commandos still require oversight, especially when it comes to advanced planning for missions, says the American commander here, who cannot be identified by virtue of his job in Special Forces. They also need help on the missions themselves, as the commandos have no aircraft to speak of and must rely on their US partners in a myriad of ways.

Yet the advent of the 3,500-strong force, now just a year old, is a natural fit in a country that has seen decades of war and where an inherent warrior ethos helps the drive toward a professional military. In Iraq, US forces training Iraqi security forces gripe that many soldiers don't have the necessary will or discipline. But trainers here say they see plenty of will – they just need to be shown the way.

A permanent home?

The base here in eastern Afghanistan is nestled amid low mountains in a relatively safe, remote area that stands in contrast to the violence of southern Afghanistan.

The base is likely to become the permanent home of the commandos. American officers here hope they can build up the program as much as possible, but unlike coalition forces training the regular Army, the Special Forces expect a long-term relationship with this base as they seek to build and then nurture the program. "We are sure these guys won't leave us," says Col. Abdul Jaber, the commander of the battalion currently undergoing training.

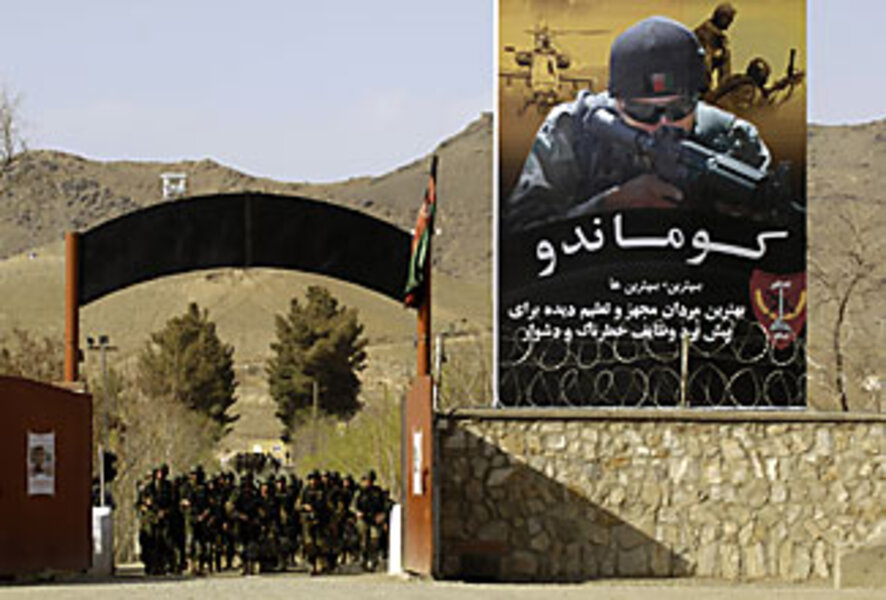

Indeed, the base generates a sense of permanence with its neat rows of tin-roofed buildings, clean streets, and the bustle of construction on its far side. Surrounded by a tall chain-link fence, there is an American side and an Afghan side, each with its own living and working areas. On the commandos' side is a black billboard featuring a steely-eyed soldier and reminds commandos that they are "the best among bests"; a well-equipped, well-trained, and brave force "to do dangerous and difficult tasks."

The difficulty of the work the commandos do means that they have been given a unique, 18-week operations cycle. The commandos receive extra pay as well as double amounts of food each day, an uncommon perk. Each battalion trains for six weeks, conducts missions for six more, and then essentially "refits and recovers" for an additional six weeks, during which time they may go on leave and see their families.

Snaking into the tire house

On a recent day, after their Afghan trainer gave them the high sign, a group of commandos moves into a practice building fabricated cheaply out of stacks of tires. As the trainer yells commands in Farsi or Pashto, the "stacks" – lines – of men snake into the rooms, weapons pointed, and yell "dum, dum dum dum," as they mock the sound of gunfire.

But something strikes the trainer as amiss. He pointedly shoves a soldier's weapon down to the ground, jolting the soldier to attention and loudly scolding him, perhaps a bit more loudly for a visitor's benefit. His message: Aim the weapon at a potential target – not absentmindedly at the ceiling above.

It's a question of showing them "what right looks like," as another American officer here says.

The training has produced four battalions, or kandaks, of about 650 commandos each, now assigned permanently around the country and two more are on the way. The commandos have begun to plan some pieces of their own counterterrorism missions, including a violent one recently in the northeastern province of Nuristan that netted key insurgents.

"What we really want to do is empower the Afghans," says the American commanding officer of the Special Forces details. Success is measured in small steps, like the commandos' budding ability to plan their own missions. Now they think at least two weeks ahead, instead of just one day ahead, trainers here say.

"For us, it's a huge step," the American officer says. But even as the commandos progress toward more independence, American Special Forces units, who count as a core mission their ability to train foreign militaries, hope to imbue their charges with the expert training that can help shape a stronger conventional Afghan Army.

The US trainers also face some education of their own. Last year, during Ramadan, in which Muslims fast during the day, the Special Forces tried to continue training. But they quickly realized that stamina was an issue. "It's always a learning process," says one officer.

But the training has translated to some tactical victories on the battlefield. One commando battalion helped American Special Forces on a recent operation in Nuristan that reportedly netted several members of the terrorist group Hizb-e-Islami Gulbuddin (HIG), who, along with the Taliban, also operate here.

The April 6 mission led to a coalition airstrike that, along with the ground fight- ing, left as many as 20 dead.

American Special Forces officials said the fight had significantly reduced the ability of the HIG to operate in the area and that the operation resulted in no civilian casualties. Officials at the Afghan Ministry of Defense called the mission a success.

At the same time, Agence France-Presse quoted a local lawmaker, Rahmatullah Rashidi, as saying that the US-Afghan attack had killed several civilians. Independent sources say local leaders have made similar claims before that were unfounded.

Better supplies needed

But US and Afghan officials acknowledge the challenges in building such a force. Illiteracy is a big issue for all the Afghan security forces, and one that is all the more apparent within the commandos, whose high-intensity work requires higher skills.

"We want these guys to have strong reading and writing skills," says Colonel Jaber, whose battalion is training now. But Jaber laments the lack of trucks, weapons, and other equipment for the program.

Supplies for the force also continue to be a problem. Red tape, onerous Department of State regulations, and manufacturing delays have all contributed to equipment shortages that have handicapped the kandaks' effectiveness, American officials say.

Each kandak, for example, is mandated to have 51 Ford Ranger pickup trucks. But each battalion has only 30 or so, American officials here say.

"Resourcing is a big issue," says another American officer. While shortages often plague any foreign force, the success of the commando program – and its potentially broader influence with the Afghan Army – shouldn't be undermined by such problems, American trainers say.

The commando mission must also compete against gear needs for the Afghan police and Army – not to mention units in Iraq. Manufacturers also sometimes can't keep up with demand, officials at Combined Security Transition Command say.

The officials acknowledge that some equipment is backordered, but point to the speed at which they have supported the building of the commandos. Indeed, the US has significantly expanded its financial to the training and equipping effort here. The budget for the training command has grown nearly seven times in the past two years, from around $1 billion in fiscal 2005 to about $7 billion in fiscal 2007.

Unity amid diversity

Ultimately, commanders here say, one area where the commandos can make a difference is in fostering a constructive sense of nationalism.

Ensuring that men from a variety of ethnic backgrounds get along is critical, American trainers say, and commandos rely on a creed under which they are brothers in arms, whether they are Pashto, Tajik, Hazaras, Uzbeks, or Turkmen.

Rigid rules govern what's acceptable and what's not: talk of politics falls in the second category. Even so, ethnic differences can be acceptable fodder for good-natured ribbing.

As 1st Sgt. Mohammed Akbar supervises the squad navigating the training at the shoot house, one of his trainers jokes that Akbar, a Hazara whose Asian background is apparent in his facial features, has a "flat nose."

But that's fine with Sergeant Akbar, a serious soldier-trainer who says the commandos' diversity is their strength. "This is all Afghan," says Akbar, as he stands atop tires in the training building and gestures to the men below him.