Conservation saved India’s tigers. Residents say, ‘Protect us, too!’

Loading...

| Uttarakhand, India

While walking to school with a classmate one day in November 2023, a teenager named Ankit stepped off the asphalt road and into the adjacent forest, seeking a bit of privacy to relieve himself. As he turned to head back to the pavement, he was slammed from behind.

“At first I thought it was my friend messing around,” recalls Ankit, who, like many in India, does not have a surname. But a second later, he hit the ground face down and felt a set of teeth sink into his right shoulder. “I knew instantly it was a tiger.”

As Ankit tells it, he was dragged deeper into the forest, behind a clump of bushes. The tiger adjusted its grip, setting its jaws around Ankit’s head. “I was sure I was going to die,” he says. “I was desperate.”

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onThe number of endangered tigers in northern India has more than doubled in the past 20 years – a triumph for conservation. But as fatal attacks on humans also increase, local residents want to prioritize safety.

Ankit lives in the north Indian state of Uttarakhand, where lowland jungles rise into forested hills that sit below soaring Himalayan peaks. It is about the size of West Virginia. In an average week, two to three people there are attacked by big cats, according to data from the Uttarakhand Forest Department.

Some 6 miles from Ankit’s home, Jim Corbett National Park has the highest density of tigers anywhere in the world. An estimated 260 tigers live within it, while another 300 or so live elsewhere in Uttarakhand, for a total of 560 cats statewide, according to the most recent tiger census.

For those who care about protecting tigers, these numbers are a triumph. In 2006, when India’s National Tiger Conservation Authority was created, Uttarakhand’s tiger population was estimated at just 178. Nationwide, the number of tigers has also grown over the past two decades, from 1,411 cats in 2006 to 3,862 today, making India home to approximately 75% of the world’s wild tigers.

But the current intensity of conflict between people and predators has caused communities to question whether Uttarakhand’s success at protecting endangered animals has come at too high a human price.

Ankit says that, while struggling for his very life, he somehow managed to reach up and grab the tiger by the tongue. Then he pulled. Hard.

The tiger, apparently surprised, released him and retreated into the jungle.

Hearing his screams, his friend ran for help to a nearby Forest Department check post, where a few forest guards were stationed. The guards refused to go in to help the teen, and wouldn’t allow anyone else to try to rescue him.

“They said, ‘No one can be saved from the jaws of a tiger – he’s gone.’ And they didn’t want to risk more lives with the tiger still nearby,” recounts Ankit’s father, Suraj, who arrived at the scene some 30 minutes after the attack. By that time, a small crowd had gathered along the road.

Suraj shouted for his son three times, and, to everyone’s shock, Ankit staggered out of the jungle. His shirt was shredded, and he was covered in blood. Among other severe injuries, his scalp had been slashed open by the tiger.

Ankit’s father immediately stripped off his shirt and wrapped it around his son’s head. Ankit remembers making it to the road, but doesn’t recall feeling any pain. He was rushed to a hospital on the back of a motorcycle, sandwiched between his father, who was driving, and another man who sat behind him, holding him in place.

The number of attacks by tigers and leopards is increasing

As the number of tigers in Uttarakhand has increased, so has the number of tiger attacks. In 2023, when Ankit was mauled, the state reported 26 attacks, including 17 fatalities. In 2006, when the National Tiger Conservation Authority was formed, there were just two, including one death.

And tigers are not the state’s only, or even most prevalent, feline threat.

One afternoon in July 2024, in a small hamlet in the Himalayan foothills near the village of Akhori, a 9-year-old girl named Poonam was playing with a neighbor.

“I called over there at 5 o’clock, wondering why she hadn’t returned yet,” Poonam’s mother, Usha Devi, says. “I was told that she’d left an hour earlier.”

A search party was organized, and that evening Poonam’s remains were discovered in the forest, a few hundred yards from her home. She’d been killed by a leopard.

Over the next few months, two more children in the village were killed by the same leopard. Schools were closed for weeks. Cages baited with goats were placed in the forest, camera traps were installed, and teams of hunters – known as shikaris – were dispatched. It wasn’t until November that the leopard was ultimately tracked down and shot. “It was watching kids playing when they killed it,” Usha Devi says.

In 2024, there were 137 people attacked by leopards in Uttarakhand, according to Forest Department figures. Fifteen died. During a spike in attacks that fall, five children were reported killed over a span of four weeks. Schools in villages across the state were shut due to what they called the “leopard menace.” Curfews were imposed.

While the Forest Department estimates there are 3,100 leopards within Uttarakhand’s borders, that figure is generally regarded by wildlife experts as unreliable, as no official census has ever been conducted. Many believe there are more, and that the population is growing.

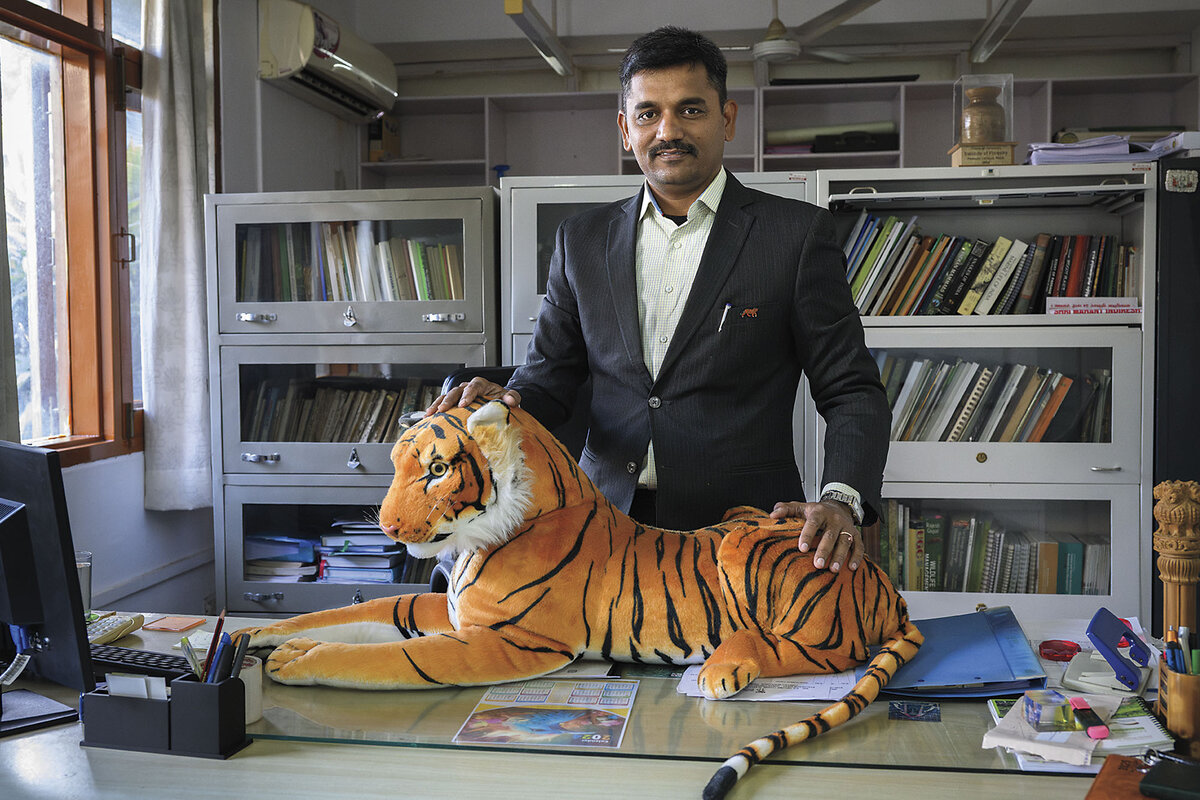

“Conservation efforts have been very successful. There’s an increase in numbers and lots of leopard sightings,” says Puneet Tomar, the officer in charge of Uttarakhand’s Tehri Forest Division, which includes the village of Akhori. Leopard encounters, too, appear to be rising. Over the past 25 years, the average number of annual attacks, measured over five-year spans, has jumped from 75 to 125 per year.

After a leopard or tiger kills or injures someone, the Forest Department typically pays 400,000 rupees (about $4,600) in compensation to families. In Ankit’s case, this wasn’t enough to cover the cost of his medical treatment. His family says it has gone deep into debt and can’t afford the further surgeries that doctors have recommended for Ankit. Others reported similar difficulties with paying for the care of wounded family members.

The dilemma of conserving tigers where people live

Uttarakhand currently faces a dilemma: how to continue protecting big cats while reducing human-wildlife conflict. For some, even one fatality is too many. Manish Kumar runs the Socialist People’s Front, a nongovernmental organization that advocates for “peasants and forest dwellers,” he explains.

“I am not against tiger conservation,” he tells me at his office in Ramnagar, just outside Corbett National Park. “But I am against the practice of conserving tigers at the cost of human life.”

He believes the government should assess the territorial needs of tigers and leopards, and then determine the number of cats Uttarakhand’s ecosystems can actually support. If there are more cats than resources and territory, he suggests “balance hunting” to reduce their populations to sustainable levels.

“Forest officials say, ‘Live together,’” Mr. Kumar says. “This is impossible. When a tiger is hungry, he will eat you.”

There are, however, strategies that researchers and government officials alike believe can greatly reduce the number of attacks while keeping guns out of the equation. The goal of the Guidelines for Human-Leopard Conflict Mitigation, published by the Indian government in 2023, is “harmonious coexistence” between humans and wildlife.

Sanjay Sondhi, a founder of Titli Trust, a nonprofit that works on reducing human-leopard conflict in Uttarakhand, says, “There are no easy answers, but the solution must be coexistence. You can’t eliminate leopards or people.”

A program run by Mr. Sondhi’s organization, called Friends of the Leopard, teaches communities nonviolent strategies that will help them stay safe. In the handful of villages where pilot projects have been launched, attacks have in fact dropped by 75%, Mr. Sondhi says. “We’ve shown that it works. The issue is how to translate intent to action across the state.”

Big-cat attacks are nothing new to the people of Uttarakhand. This is the region where Jim Corbett, for whom the park is named, rose to fame as a shikari in the early decades of the 20th century. In his classic memoirs, he recounts tracking the Champawat Tiger, which reportedly killed 236 people over four years in the eastern part of the state and 200 more in neighboring Nepal. He also writes of the hunt for the Leopard of Rudraprayag, which claimed a reported 125 lives over eight years.

“People here have a tolerance for sharing space with wild animals,” says C. Ramesh, a researcher at the Wildlife Institute of India who worked on the Guidelines for Human-Leopard Conflict Mitigation. “But that tolerance level has gone down.”

Residents of villages where attacks have occurred say this is because the situation, as they’ve known it during their own lifetimes, has changed.

“It was not like this earlier,” says Vipin Chandra Sharma, whose 19-year-old daughter, Nikita Sharma, was killed by a tiger while cutting grass in her family’s field with a number of other women. She was its third victim in the area. “We hear tigers or leopards growling every day. The Forest Department issued a warning two weeks ago saying, ‘Don’t go out between 4 p.m. and 9 a.m. – if you get attacked it’s not our responsibility.’”

Feeling that they have nowhere else to go, locals have had to learn to overcome their fears. I visited homes in several villages where children had been grabbed by leopards mere feet from their houses. Some survived – like Siya, who at age 8 in April 2024 was severely injured after a leopard dragged her into the forest before releasing her. Others did not.

“We have seen the worst,” says Kavita Devi, whose 9-year-old son, Aarav Singh, was killed by a leopard while crossing the family’s courtyard in Koirali village. “So what is there to be scared of?” Still, she makes sure her three remaining children are always inside before sunset.

A perspective from big cat hunters

When a big cat proves to be a danger to people, it will be trapped or tranquilized and relocated – if it can be found. Sometimes, when a leopard – or, much more rarely, a tiger – becomes a repeat offender, the government will issue orders to shoot it.

Over the past decade or so, the most prolific shikari in Uttarakhand has been Joy Hukil. By his own count, Mr. Hukil, a thoughtful and soft-spoken man with a great respect for leopards, has killed 47 of the cats. His difficult and exhausting work is an unpaid public service, and he covers his own expenses, from food to ammunition.

“There is more conflict now than in the past,” he says at his spartanly furnished stone house, built in the town of Pauri by 19th-century American missionaries. “Thirty years back, there was no fear of leopards. People used to be afraid of evil spirits lurking in every corner. Nowadays, everyone has forgotten about the spirits.”

Mr. Hukil believes one reason leopards attack is that their base of natural prey in the forests has dwindled.

“It’s a pity. Leopards, they’re designed to eat meat. They have no other option, so they come close to human habitations and sometimes some of them decide to kill people,” he says.

No one knows whether the prey base has shrunk, Mr. Tomar, the forest officer, tells me, because that hasn’t been studied.

“Less prey may be part of the problem,” he says. “But there are no numbers on how much a part of the problem it is. Even if deer are there,” he continues, “leopards will come out of the forest for easy prey.” He thinks that when attacks occur near houses, leopards are hunting cattle and dogs, “and they happen to encounter kids.”

Mr. Sondhi of Titli Trust says that the reasons attacks occur where they do are often a mystery. “There is no difference between areas of high and low conflict. The habitats are similar, and habitat quality is similar. It just seems random,” he says.

“Sometimes there’s just no way to explain leopard behavior,” he adds. “There are many things we don’t know.”

Among those things are, How much is the behavior of big cats changing? And what is their motive when they attack?

In his 1944 book, “Man-eaters of Kumaon,” Corbett wrote what has long been a tenet of human-tiger conflict:

“It is only when tigers have been incapacitated through wounds or old age that, in order to live, they are compelled to take to a diet of human flesh.” People, in other words, are easy prey, he believed, but healthy tigers don’t bother to hunt them. For cats that do, it’s a matter of survival.

This no longer seems to be true – at least not with the current spate of attacks, says Dushyant Sharma, senior veterinary officer at Corbett Tiger Reserve. In charge of teams that relocate problem cats, he says, “Out of 20 tigers captured, only 1 or 2 is old or injured.”

All of the Forest Department officials I spoke with, however, reject the idea that some cats are “man-eaters” that deliberately hunt people. Instead, they attribute attacks to “accidental encounters,” when a tiger or leopard is surprised by a person, or cases of “mistaken identity.” “A leopard doesn’t want to kill any child,” says Dhruv Martolia, divisional forest officer in the Bageshwar area, during a phone conversation.

When I talked to Pradeep Dhaulakhandi, another divisional forest officer in Almora, I referred to one leopard held at the Almora Rescue Centre for over a decade as a “man-eater,” since it has been deemed too dangerous to release back into the wild. He immediately scolded me for using that term.

But Dr. Ramesh of the Wildlife Institute of India explains that while “Leopards usually try to avoid contact with people,” they are extremely smart, highly adaptable, and able to live very close to towns and villages.

“Once a leopard is habituated to human presence, its shyness will go away,” he says. “Many attacks are the result of surprise encounters, but leopards can learn that humans have no self-protection, that they are easy prey. And if cubs taste human flesh, they learn they can hunt humans.” This knowledge, Dr. Ramesh adds, can pass from one generation of leopards to another.

When I ask Mr. Hukil, the shikari, for his thoughts, he replies, “Once a leopard kills a human and eats the body, humans are added to their menu.” He dismisses the notion that leopards mistake people for other animals. “Leopards can see far better than us. They are aware who they are attacking.”

But, he points out, “They’re hungry; their numbers are in the thousands, but relatively few leopards are actually killing humans.”

A path toward a harmonious coexistence

A common assumption regarding the roots of human-wildlife conflict is that people are increasingly encroaching on wildlands and reaping the consequences. But in much of Uttarakhand, the opposite is also true.

Many rural villagers are leaving remote areas for better jobs, better schools, and better health care. The crop fields that they once tended have become overgrown with brush.

Situated between homes and the forest, these fields are a crucial buffer zone between humans and wildlife habitats. When they become untended and overgrown, that buffer disappears, and wildlands begin encroaching on residential areas. Attacks become more likely, and when they occur, more people move away out of fear.

“Human-wildlife conflict is now one of the biggest reasons for migration, and migration is a reason why these killings keep happening,” Mr. Hukil says. “It’s a self-perpetuating cycle.”

One of the top tactics for reducing the conflict, recommended in the Guidelines for Human-Leopard Conflict Mitigation and by Friends of the Leopard, is to keep fallow fields clean.

Other strategies include improving lighting in villages and around homes; reducing the number of stray cattle, since many people suspect they lure the predators, which then attack people instead; and improving waste management, as trash draws dogs, cows, and other animals that big cats hunt. “When garbage dumps are located on the periphery of or inside a village/town, high levels of conflict may result,” the guidelines note.

These guidelines, however, which include ambitious proposals that could improve our understanding of leopard behavior patterns, are merely suggestions, not rules.

When I asked how rural residents of Uttarakhand can be persuaded to support big-cat conservation efforts despite their fears of being attacked, Mr. Sondhi, Dr. Ramesh, and others reply that respect for animals is ingrained in the region’s culture – and the Hindu religion.

This perspective can be reinforced by education, informing people about the benefits that healthy populations of apex predators have for the environment as a whole. Still, this is a project that will need patience.

Any path toward a harmonious coexistence must be sensitive to the fear that locals are currently living with, Dr. Ramesh says. He adds, “It can seem out of touch for people in the city to say, ‘You have to have high tolerance,’ when we are not the ones living with it day to day. But we need to mitigate the conflict while protecting the wildlife.”

Many of the people I talked to who had endured the trauma of attacks by big cats can support that sentiment. But they give it a slightly different emphasis.

“Put all the tigers in the world in Corbett, fine. But protect us, too,” says Ankit’s father, Suraj. “If tigers are important, we people are important, too.”

Ankit himself ultimately hopes to work for the Forest Department one day.

“No one tried to save me,” Ankit says. “But I will try to save people.”