How North Korea is capitalizing on Russia’s war woes

Loading...

| Beijing and Moscow

North Korea has exploited the Ukraine war to gain geopolitical leverage with Russia – forging a bold new alliance with President Vladimir Putin that poses security risks for Northeast Asia and the world.

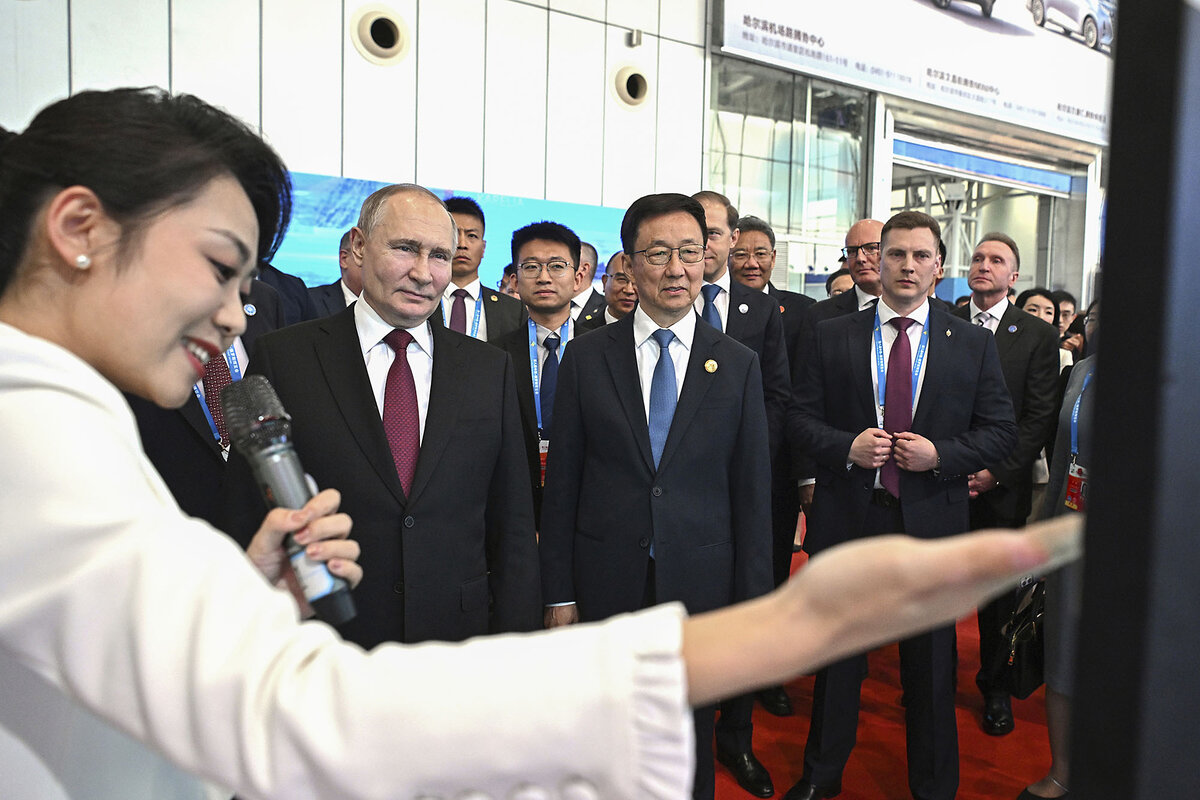

Russia-North Korea relations have advanced rapidly following North Korean leader Kim Jong Un’s trip to Russia last September, and since then Pyongyang has sent an estimated 11,000 containers of munitions to Russia, according to the U.S. State Department. During Mr. Putin’s visit last week to Pyongyang – his first in 24 years – the two leaders agreed to a “comprehensive strategic partnership,” Russia’s highest level of bilateral ties.

The centerpiece of the sweeping treaty is its mutual defense clause. It holds that if an armed invasion of North Korea puts the country in a “state of war,” Russia will be required to provide military assistance “with all means in its possession” to North Korea “without delay” – and vice versa. While the details of the treaty remain secret, that clause could effectively give North Korea shelter under Russia’s nuclear shield.

Why We Wrote This

Vladimir Putin’s brief Asia tour marks his latest bid to rally old allies of the Soviet Union, with major ramifications for international security.

“This treaty has significant potential to endanger regional as well as global security,” says Rachel Minyoung Lee, a senior fellow for the Korea Program at the Stimson Center in Washington. “The treaty paves the way for Russia to become involved militarily in the Korean Peninsula and Northeast Asia if needed by locking in North Korea,” she says. “This provides North Korea with an extra nuclear cover against its perceived external threats, namely the United States, South Korea, and even China.”

Global reactions

In joining forces, Mr. Putin and Mr. Kim share the goals of breaking out of their pariah status, defying U.S.-led sanctions on their regimes, and promoting a multipolar world order, experts say. But the heightened cooperation by two actors widely viewed as unpredictable and disruptive could backfire.

The U.S., Japan, and South Korea issued a joint statement on Sunday strongly condemning the deepening military cooperation between Pyongyang and Moscow, and pledging to counter the threat from North Korea. In reaction to the treaty, South Korea has indicated it could consider providing weapons to Ukraine.

For the U.S. and its Asian allies, the pact heightens the risk that just as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine shattered decades of peace in Europe, a hot war could break out in Asia – especially amid rising tensions on the Korean Peninsula, and in the South China Sea and Taiwan Strait. This, in turn, underscores the urgency of the significant strategy to bolster defense cooperation that is already underway between Washington, Tokyo, and Seoul.

For its part, China has remained publicly aloof from the upgraded ties between Russia and North Korea – Beijing’s two closest partners – seeing both pros and cons in the pact, experts say.

On one hand, “the Chinese enjoy the fact that there will be more distraction of the United States,” says Yun Sun, director of the China Program at the Stimson Center in Washington. Russia and North Korea are “not working together against China, they’re working together against the United States,” she says.

Yet China also worries that the optics of a trilateral alignment with Russia and North Korea will limit its room to maneuver. “This image of a Northeast Asia ‘axis of evil’ that I think both North Korea and Russia have tried to project … that’s something the Chinese have tried very hard to avoid,” says Ms. Sun. “That would eliminate China’s space to work and cooperate with Europe and also with Japan and South Korea.”

Finally, by drawing closer, Moscow and Pyongyang gain a degree of new leverage with Beijing. “China has had almost an entire monopoly of influence over both Russia and North Korea. So naturally, China would prefer not to lose that monopoly,” says Ms. Sun.

Nevertheless, Beijing’s official position is that Russia and North Korea can conduct their relationship as they see fit – and the two junior partners are forging ahead.

“Russia sees North Korea as very important because it has provided … millions of rounds of munitions” for Russian forces in Ukraine, says Ian Storey, senior fellow at the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute in Singapore and an expert in Asian security.

By clinching a new strategic partnership with Mr. Putin, Mr. Kim opens the door to significant military, technology, and economic benefits for Pyongyang. It illustrates how Mr. Kim has profited from Russia’s battlefield shortages in Ukraine to dramatically boost his bargaining position with Moscow – a coup for his isolated dictatorship.

But North Korea wasn’t Mr. Putin’s only stop in Asia.

Putin seeks friends in Asia

Vietnam’s Communist Party-led regime, which benefited from extensive support from the Soviet Union during the Cold War, welcomed Mr. Putin warmly last week. “Russia is still seen as an old friend” by Hanoi, says Dr. Storey, a specialist in Russian defense ties in Southeast Asia. Vietnam remains dependent on Russia for military equipment, he adds, as most of its military hardware is Russian-made.

Yet while Hanoi seeks to cooperate with Moscow on energy, trade, and defense, it is unlikely to offer military support for Russia in Ukraine, Dr. Storey says. That could jeopardize Vietnam’s “bamboo diplomacy,” which seeks to balance its ties with Russia, China, and the U.S. “If Vietnamese-manufactured shells start ending up in Ukraine, the Americans and the Europeans would be very angry,” and they are Vietnam’s largest trading partners, he says.

In contrast, experts say the Russia-North Korea treaty seems intended to give legitimacy to North Korea’s provision of weapons to help Russia fight the war in Ukraine. It also paves the way for Russia to provide technology for North Korea’s space and nuclear energy programs, which could help advance Pyongyang’s weapons programs.

“We do not rule out supplying weapons to other countries, including the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea,” Mr. Putin said last week, according to Russian state-owned media.

“North Korea can produce masses of cheap artillery shells, drones, and battlefield missiles. That’s what Russia needs right now,” says Sergei Markov, a former Kremlin advisor. In turn, “North Korea wants technical assistance in missiles and satellite technology. Russia could provide this, but the problem is [U.N. Security Council] sanctions. We do not know at this point whether Putin has decided to continue obeying the sanctions, or to violate them openly, or do it secretly.”

Russia’s willingness to provide technical support to upgrade North Korean military capabilities will “be a function of Russia’s need of North Korean munitions in turn,” says Ankit Panda, the Stanton senior fellow in the Nuclear Policy Program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace in Washington.

Few tools exist for the U.S. and its allies to block such cooperation between Russia and North Korea, which share a land border and adjacent territorial waters. “They can freely conduct transfers of any kind – economic transfers, military transfers – as they see fit. Sanctions are going to be limited in dissuading cooperation,” he says. “Russia and North Korea are largely … beyond giving any care to reputational concerns internationally.”