Letter from Beijing: Behind China’s warm welcome of two US vets

Loading...

| Beijing

Two American veterans who fought to defend China from Japan during World War II – retired Capt. Harry Moyer and retired Tech. Sgt. Melvin “Mel” McMullen – are flying high on a new mission.

In the 1940s, the young aviators joined the “Flying Tigers,” the popular name for Americans serving with the 14th Air Force in China, commanded by Maj. Gen. Claire Chennault. With the benefit of that long lens, the 103-year-old Captain Moyer and 98-year-old Sergeant McMullen arrived in Beijing this week hoping to remind both Americans and Chinese of a powerful chapter in the countries’ shared history – one of extraordinary compassion and sacrifice – and encourage grassroots contacts despite tensions between Washington and Beijing.

During dire combat moments in China, “we knew that the best way – maybe the only way – we could survive was to fly our plane ... far away from the target area so that we might be picked up by a brave villager,” Sergeant McMullen said Monday at a ceremony honoring the visiting Flying Tigers delegation at the U.S. Embassy in Beijing.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onIn Beijing, the honoring of two American veterans who fought for China during World War II – and their stories of courage and compassion – underscores the importance of people-to-people ties, especially as the U.S. and China aim to stabilize relations.

Highlighting such bonds is part of a recent ramping up of people-to-people ties by China and the United States. Both sides hope the exchanges will add ballast as they work to stabilize relations and prepare for a widely anticipated meeting – confirmed by the White House on Tuesday – between President Joe Biden and Chinese leader Xi Jinping in San Francisco in November.

Beyond possible agreements in areas such as counternarcotics, climate, travel, and technology, the U.S. and China have broad objectives for the meeting, experts say.

Washington hopes that a successful Biden-Xi meeting will “unlock, especially in the Chinese system ... [a] clear signal by Xi Jinping that it’s safe to engage with the Americans,” says Jude Blanchette, Freeman Chair in China Studies at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington.

For its part, Beijing believes a meeting will “position Xi Jinping well domestically,” and that “stabilizing the relationship ... gives them a better chance to moderate future U.S. actions,” he says.

Warm welcome

As U.S.-China relations have sharply deteriorated, public opinion has soured as well, with surveys indicating most Americans hold negative views of China, and vice versa.

Both governments are now are working to counter this trend by strengthening cultural, educational, and business exchanges. The U.S., for example, welcomed a Beijing dance troupe to perform at a Chinese cultural festival in Washington this past September, and Mr. Biden sent a letter of congratulations to the Chinese Americans who organized the event.

Mr. Xi has also publicly advocated for increased exchanges between ordinary Chinese and Americans in recent months. “In growing China-U.S. relations, the foundation lies in the people, and the hope,” he said last week.

When Captain Moyer, Sergeant McMullen, and Sino-American Aviation Heritage Foundation Chairman Jeffery Greene together sent a letter to Mr. Xi in advance of their China trip, Mr. Xi wrote back. His letter featured prominently in China’s state-run media.

“In the past, our two peoples fought the Japanese fascists together, and forged a deep friendship that withstood the test of blood and fire,” Mr. Xi wrote, according to a front-page article in People’s Daily, the Communist Party’s main mouthpiece. He called for “a new generation of Flying Tigers” to advance U.S.-China relations.

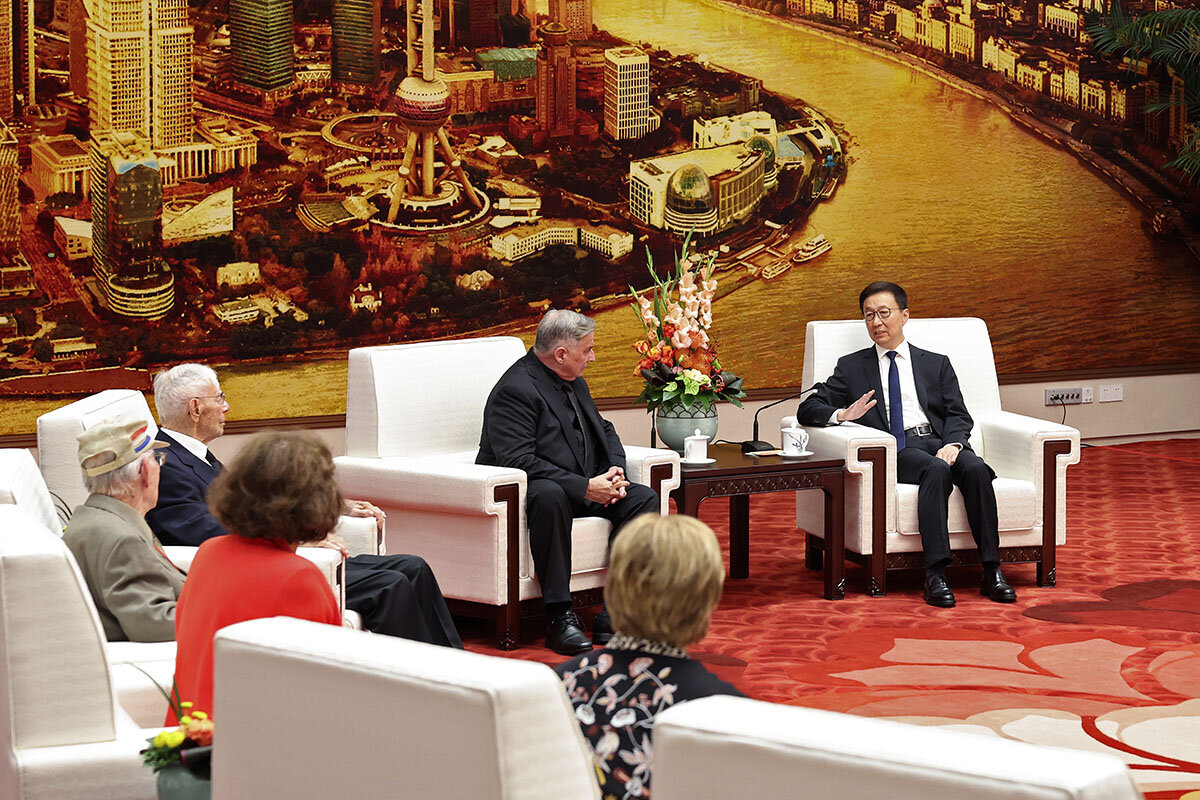

Against this backdrop, the visit this week by Captain Moyer and Sergeant McMullen created a bit of a Chinese media sensation. National television reports and posts on China’s popular social media platform Weibo showed them chatting with Vice President Han Zheng, strolling along the Great Wall in olive-green World War II bomber jackets, and saluting a statue of General Chennault, who died in 1958. Hailing the visit with unusually upbeat remarks, Foreign Ministry spokesperson Wang Wenbin on Wednesday called on Chinese and Americans from all walks of life to help “write a new chapter” in U.S.-China cooperation.

An enduring love

Fanfare aside, listening to Captain Moyer and Sergeant McMullen’s down-to-earth accounts of their wartime China service, one can’t miss the compassion they felt for ordinary Chinese – and received in return.

Growing up in Ohio, Captain Moyer loved visiting his father’s friend “Eddie,” a warmhearted Chinese man who ran a local restaurant. A 1937 film based on the novel “The Good Earth” by Pearl S. Buck also left a deep impression. “It depicted the Chinese peasants tending their rice fields ... and the greenness,” he told the embassy gathering. “I can’t get that picture out of my mind.”

When Japan launched a full-scale invasion of China in 1937, Captain Moyer was troubled by reports of Japanese atrocities. After being recruited in college by the U.S. Army Air Corps, he earned his fighter pilot wings, trained on the Curtiss P-40 “Warhawk,” and deployed with the 59th Fighter Squadron of the 33rd Fighter Group to combat German and Italian forces in North Africa and Italy. Then in 1944, when the 33rd received orders for the China-India-Burma theater, he had a chance to return to the U.S. – but, thinking of “Eddie” and the overall suffering of China’s people, he declined.

“I told the commanding officer, ‘I don’t want any orders to take me home. I’m going to go to China,’” he said. “And that’s what I did.”

Upon landing in Kunming, China, General Chennault greeted him and the other 14th Air Force recruits, leaving a big impression on Captain Moyer. From there he flew to Sichuan province, with the job of defending the B-29 bombers striking Japan’s islands. He saw the rice fields. Chinese people “were so friendly,” he said. “They took care of us.”

“People are the same”

Sergeant McMullen, too, put his faith in Chinese villagers. An aerial gunner and assistant flight engineer, Sergeant McMullen was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross for his service with the 14th Air Force’s 308th Bomber Group (Heavy), which flew B-24 Liberators in support of Chinese ground forces. He heard many stories of U.S. airmen being rescued after their planes went down.

“They would hide the airman by day, and by night, they would move him – from village to village – [until] they could finally be picked up by the Americans,” he told the embassy gathering.

Sheltering Americans was dangerous work. When most of the U.S. bombers involved in the 1942 Doolittle raid on Tokyo had to abandon their planes over eastern China, families there successfully safeguarded the airmen. But Japan later launched a brutal retaliation campaign, wiping out entire villages.

“There are hundreds of airmen that owe their life to those brave, brave people,” said Sergeant McMullen. “That’s something that we should all understand. People are the same. Governments may be different, but the people actually always have one desire, and that is to live and to raise their families in peace and in the customs of their predecessors.”

In all, more than 2,000 members of the Flying Tigers gave their lives to defend China, while thousands of Chinese died protecting American pilots in distress, according to official Chinese figures. General Chennault’s granddaughter, Nell Calloway, and Mr. Greene, from the Sino-American Aviation Heritage Foundation, work to educate young people in both countries about that shared sacrifice.

“Americans don’t know that story,” Ms. Calloway told the gathering.

Captain Moyer, too, has a soft spot for China’s people, under his tough exterior. Holding a Guinness World Record for being the oldest licensed pilot – he made a solo flight on his 100th birthday – the former Flying Tiger celebrated his 103rd birthday in Beijing on Monday, cutting a cake decorated with the blue-and-orange Flying Tiger emblem.

Returning once again to China, he said, “is just like putting on an old coat. ... It’s a great feeling. They put out their hearts for you.”