Balloon burst hopes for US-China trust-building. What now?

Loading...

A rare opportunity for the United States and China to revive critical dialogues blew up in a plume of smoke this weekend as a U.S. Air Force jet downed a suspected Chinese spy balloon off the South Carolina coast.

Pentagon chief Lloyd Austin said China’s government was using the balloon, which had traversed American territory for seven days, “to surveil strategic sites in the continental United States.” Beijing, claiming the balloon was a civilian airship used primarily for meteorological research and blown off course and into the U.S. by “accident,” protested the U.S. strike as “a clear overreaction.”

Regardless of the balloon’s mission, the crisis was exacerbated by a failure of real-time communication and led Washington to postpone the Feb. 5-6 visit to Beijing of U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken, who would have been the most senior American official to visit China in more than four years.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onThe crisis over China’s weather or spy balloon has derailed a critical opportunity for restoring talks and building trust between Beijing and Washington – and also reveals why they are so important.

“Why didn’t they [Chinese officials] tell the Americans, ‘Sorry, our balloon drifted into your territory?’” says Yun Sun, a senior fellow and co-director of the East Asia Program and director of the China Program at the Stimson Center. “Did they underestimate the severity of the situation?”

Indeed, the balloon incursion underscores a glaring lack of crisis management mechanisms, communications channels, and, ultimately, trust between China and the U.S., experts say. The result is an ever-increasing risk that mistakes or miscalculations between the superpowers will spiral into conflict.

“It is a very dangerous reality that we’re dealing with,” says Ms. Sun. “This is just a balloon, right? If we’re talking about, say, a skirmish or incident in the Taiwan Strait, then it’s going to be much more severe than this.”

Why China won’t pick up the phone

Nowadays, when the Pentagon picks up the hotline to dial China’s military during a crisis, often all it hears is an extended ring tone.

From silent communications channels to canceled meetings, U.S.-China military contacts are at a low point, even as tensions between the two countries make mechanisms for managing crises – such as the balloon incident – all the more vital, experts say.

“Improving crisis prevention and crisis management has never been more important in this relationship, and it has been derailed, most recently by the Chinese,” says Michael Swaine, director of the East Asia Program at the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft in Washington.

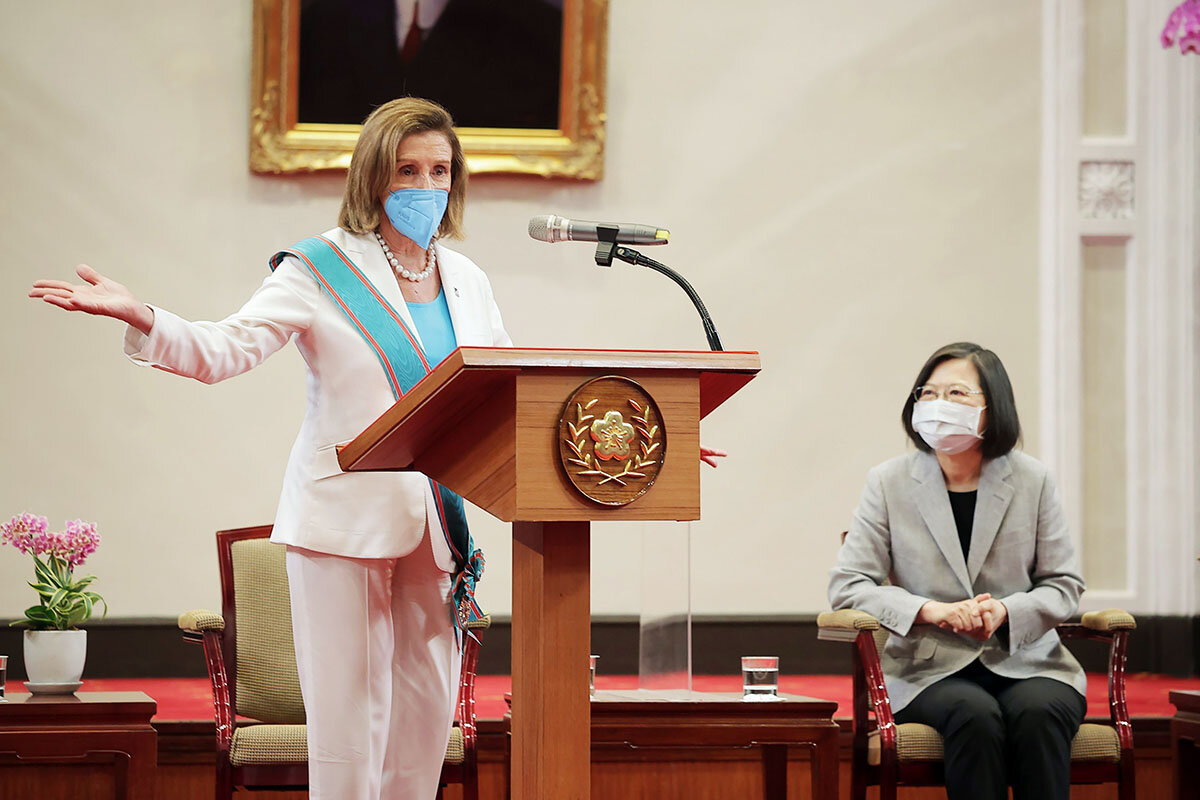

Beijing canceled regular military-to-military dialogues between the two countries last year to protest the August visit of then-U.S. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi to Taiwan, the self-governed island off mainland China’s southern coast that Beijing claims as a province. “There is no doubt that a possibility of a misfire will increase” as a result of the severed dialogues, China’s official Global Times newspaper commented at the time.

Three U.S.-China hotlines set up starting in 1997 still exist, but their effectiveness has proved limited, in part because Beijing doesn’t always answer.

“The Chinese PLA [People’s Liberation Army] has made it quite a pattern, especially when bilateral relations are not good,” says Ms. Sun. “Picking up the phone is a political statement” and requires approval from senior leaders, she says. “The Chinese don’t see this mechanism for what it is; they see it as a political bargaining chip.”

Indeed, compounding these issues are starkly different Chinese and American understandings of crisis prevention and management, experts say.

For its part, the U.S. sees crisis management as a way to de-escalate and defuse potential conflicts. Beijing’s strategy aims first to prevent crises by simply demanding that the U.S. military avoid operating near China. In cases of a crisis, it holds that any communications should be used as a form of coercion to deter military action.

“They are seeing the U.S. as driving the crisis, so the U.S. needs to take responsibility,” says Dr. Swaine.

“Hotlines are not meant to resolve the crisis, but to empower higher-level organs within the PRC [People’s Republic of China] to signal resolve, assign blame, and stall until Beijing stakes out a position of maximum pressure and leverage over the United States,” says a Rand Corp. analysis of the hotlines published last July.

The U.S.-China disconnect over crisis management contrasts sharply with Cold War-era practices, experts say. The U.S. and former Soviet Union “had rules of engagement in the sea and air, even over mutual surveillance [by planes],” Miles Yu, director of the Hudson Institute’s China Center, said in a C-SPAN appearance Sunday. But, he said, “China has consistently refused to get into this managerial crisis mode.”

Will the balloon blow over?

Despite profound differences and distrust, Beijing and Washington had appeared poised to address restoring not only the military-to-military channels but also dialogues on counternarcotics and other key topics during Secretary Blinken’s visit.

That still may happen after the balloon incident blows over. Mr. Blinken told Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi that the “high-altitude PRC surveillance balloon in U.S. airspace” was “an irresponsible act and a clear violation of U.S. sovereignty ... that undermined the purpose of the trip.” But he added that he was prepared to visit Beijing “as soon as conditions allow.” Mr. Blinken was expected to meet Chinese leader Xi Jinping.

The U.S. Navy has begun recovering debris from the balloon – an effort that will reveal more information about the balloon’s capabilities and China’s intentions, White House spokesperson John Kirby said Monday. China said another of its balloons – spotted over Latin America – had deviated far off course.

“The Chinese have been developing more uses for these big balloons,” including for launching weapons tests, says Dr. Swaine. “So it’s not surprising to find other balloons floating around in other places.”

The U.S. and China both have strong motivations to stabilize relations and build upon progress made when President Joe Biden met with Mr. Xi on the sidelines of the Group of 20 meeting in Indonesia in November.

“The U.S. is focused on managing the relationship, preventing it from deteriorating to the point of overt confrontation and conflict,” particularly over Taiwan, says Drew Thompson, a visiting senior research fellow at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy at the National University of Singapore.

China’s focus on recovering from a major COVID-19 outbreak and reinvigorating its slowed economy requires easing tensions with the U.S. and other trade partners. Three years of self-imposed isolation under Mr. Xi’s stringent “zero-COVID” policy have taken a toll on China’s heft in the Indo-Pacific, according to the Asia Power Index, an annual ranking of 26 countries released by the Lowy Institute on Sunday.

Smoother ties between Washington and Beijing could help set the stage for Mr. Xi to attend the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation leaders’ meeting in San Francisco in November.

“Neither we nor the Chinese are going to dominate each other ... and neither of us is going to capitulate to the other, so we’ve got to find some kind of middle ground,” says Dr. Swaine.