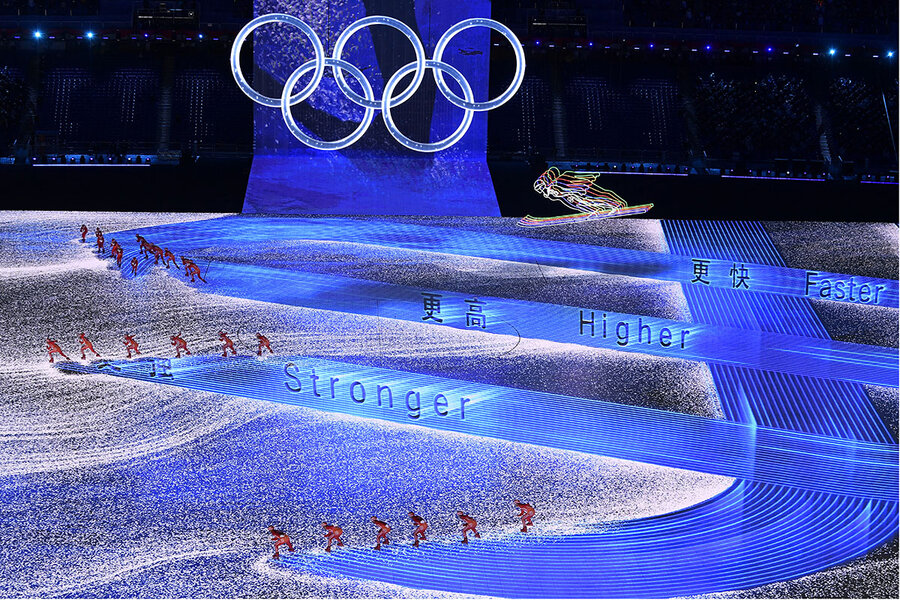

No more charm offensive: How China’s Olympics goals have shifted

Loading...

Fourteen years ago, China staged the 2008 Summer Olympics, proudly showcasing its sports talent and ancient civilization before a global audience eagerly courted by Beijing.

An opening extravaganza celebrated Chinese inventions from gunpowder to printing, while thousands of synchronized drummers chanted a Confucian saying about the delights of “friends coming from afar.”

“I can still remember the enthusiasm of Chinese at the time,” says Mu Yue, who navigated huge crowds of Chinese and foreigners as a photo assistant at the Games. Wild cheering and the glitter of flashing cameras filled stadiums, she recalls, along with endless renditions of the song “Beijing Welcomes You.”

Why We Wrote This

China used the 2008 Olympics to reintroduce itself to the world, but this year’s Games are all about the domestic audience. Comparing the events offers insight into how Beijing’s goals and priorities have changed.

But such exuberant outreach to the world has largely been missing during the lead-up to the 2022 Games. Under China’s zero-tolerance pandemic policy, experts say the Olympics will unfold in a tightly closed loop, as China’s leaders focus mainly on how the Games are viewed domestically.

“In terms of the image that China seeks to project, the main priority ... is the domestic audience, and showing people back in China that China is a respected country, that it’s seen as a leader,” says Peter Martin, author of “China’s Civilian Army,” a book about China’s growing power and diplomatic assertiveness.

Shift in strategy

In 2008, the Olympics were part of a broader diplomatic charm offensive by Beijing – one that included economic reforms and a softening of China’s stance on thorny issues from territorial disputes to human rights, says Mr. Martin. It was aimed at making Beijing’s Communist Party leadership “more palatable to the outside world,” he says.

Today, Beijing’s leaders project more confidence in China’s power and position, and feel they have less to prove to the world, analysts say. China’s gross domestic product has tripled since 2008, as the country rose to become the world’s top exporter and the second-largest economy.

In the past decade, China has adopted a more assertive foreign policy, pushed for territorial gains, and conducted a sometimes abrasive “wolf warrior” diplomacy – all factors that have hurt its image in the West, Japan, and other advanced economies. Beijing recently threatened countermeasures against countries that have imposed diplomatic boycotts of the Games to protest human rights violations in China. It has also warned that athletes will face punishment for speech that violates the “Olympic spirit.”

“In the first Olympic Games, Beijing tried to please the whole world, but now I think they really don’t care about world opinion,” says Xu Guoqi, a history professor at the University of Hong Kong and author of “Olympic Dreams: China and Sports, 1895-2008.”

Instead, China’s leaders increasingly present China as a model for other countries to emulate, citing, for example, successful pandemic control measures and smooth Olympic preparations as evidence of the effectiveness of Communist Party rule.

To be sure, hosting China’s first Winter Olympics, on schedule, during a global pandemic, is a massive undertaking and major accomplishment. “If China can deliver the Games ... on time, that’s a big success for everyone – for the host, for IOC [the International Olympic Committee], and especially for [Chinese leader] Xi Jinping,” says Dr. Xu.

Beijing’s message is clear: “This is a challenge implicitly that no other country could do, and therefore it shows the direction that Xi Jinping and his colleagues are setting is the best one for China,” says David Bachman, Henry M. Jackson professor of international studies at the University of Washington.

Mr. Xi has put his stamp on the Games – overseeing China’s winning 2015 bid to host the event, inspecting ski slopes and ice arenas, and announcing the opening of the Games on Friday. “These are Xi Jinping’s Games,” and will form part of his legacy as he prepares this year to gain a third term as China’s top leader, says Dr. Xu.

Focused on domestic opinion, Mr. Xi has cast the Games as boosting public faith in what he calls China’s inevitable progress toward a “great rejuvenation.” The administration’s goals include eradicating extreme poverty, which Mr. Xi declared accomplished in 2020, and transforming China into a fully developed nation by the country’s centennial in 2049.

“The successful hosting of Beijing 2022 will ... enhance our confidence in realizing the rejuvenation of the Chinese nation,” Mr. Xi said last month, according to the official Xinhua News Agency.

Audience apathy

Yet despite the Chinese leadership’s hopes that the Games will resonate at home, China’s public is showing little interest, citizens and experts say. “I have rarely seen any reports on social media about the Winter Olympics,” says Ms. Mu, who asked to be identified by a pseudonym to protect her identity.

“The Olympic Games seem to not catch our eyes,” says Brandon Zhang, a graduate student from southern China who recently arrived in Seattle to begin a doctoral degree. Although he is an avid skier – a sport he picked up while studying in Beijing – Mr. Zhang won’t tune in to the Winter Games. “We would rather hang out with family members than watch the boring Games,” he says.

Winter sports such as skiing are not extremely popular in China, in part because of the landscape. “Snow is not a common thing for us, and skiing is kind of a luxurious activity for common people,” says Mr. Zhang, adding that many Chinese parents consider the sport dangerous.

In contrast, most Chinese people have opportunities to play pingpong or basketball or to run, he says, so they enjoy the Summer Games more.

Indeed, for many Chinese such as Ms. Mu and Mr. Zhang, there is no comparison between the subdued atmosphere surrounding the Winter Games and the heady optimism, euphoria, and cosmopolitan spirit that dominated the 2008 Olympics.

“It’s emotional” to reflect on those August days, even now, Mr. Zhang says. Then a high school student, he couldn’t afford tickets to attend any Olympic events, but he and his family watched them on television at home in Guangzhou for as many as 10 hours a day. The 2008 Olympics “are one of the most important events in China,” he says. “It’s a beautiful memory of my childhood.”

China captured 48 gold medals in the 2008 Summer Games, more than any other country. At the last Winter Olympics in South Korea, China won one gold medal.

“Now you can see, nobody gets excited at all; nobody even bothers to pay attention,” says Dr. Xu. “They know basically nothing extraordinary will come out of this Games compared to what happened 14 years ago.”