Is China ensnaring poor countries by building their infrastructure?

Loading...

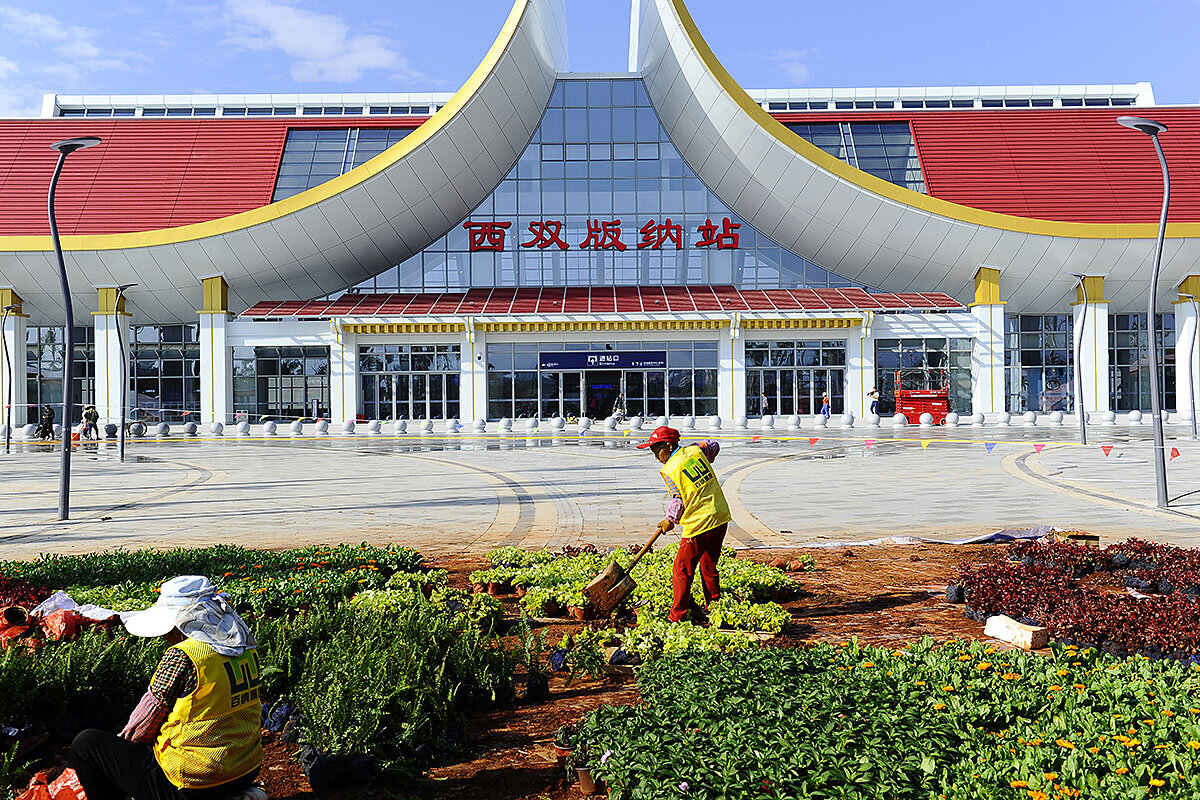

Snaking around rugged mountains and over deep river valleys, a train raced along a $5.9 billion Chinese-built railway connecting Laos and China this month, its inaugural run marking the debut of China’s first international rail network.

For Laos, a landlocked nation of 7 million, the 257-mile line from the Laotian capital of Vientiane north to China’s border creates a link to global supply chains that could help Laos attract investment and trade, create jobs, and fuel economic growth. For China, the project is the first phase of an ambitious strategy to expand its rail network through Laos, Thailand, and Malaysia to Singapore.

Yet the debt generated by the venture is a source of concern not just for Laos but also China, experts say, as the economic benefits could take years to realize. And the worries on both sides underscore a growing debate over Chinese leader Xi Jinping’s signature Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), of which the China-Laos railway is a key regional link, and whether it amounts to “debt-trap diplomacy.”

Why We Wrote This

China is often depicted as a predatory lender. But when it comes to infrastructure, that narrative doesn’t capture the full view – and risks casting nations as victims when they aren’t necessarily.

The BRI is a massive program – estimated at $1 trillion – launched in 2014 to build a network of ports, railways, and roads linking China more closely with the rest of Asia, Africa, and Europe. Since 2017, Beijing has faced criticism from foreign officials and academics for using its financing and infrastructure projects to ensnare poor countries with heavy debt loads and thereby win strategic leverage. But some analysts question whether this narrative tells the whole story, saying instead that it oversimplifies and distorts the motivations, risks, and relationships between China and the countries accepting BRI projects.

“It’s much more a creditor trap than a debt trap at this point,” says Deborah Brautigam, professor of International Political Economy at the School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS) at Johns Hopkins University.

An infrastructure gap

To be sure, there are cautionary cases – such as the often-cited granting by Sri Lanka of a 99-year lease on its Hambantota port to a Chinese company in 2017 to help relieve its debt woes. But Dr. Brautigam and other experts see Beijing less as a predatory lender seeking to force defaults on vulnerable developing countries and more as a new player in international construction learning by trial and error – “crossing the river by feeling the stones,” as the Chinese saying goes.

Another key factor – downplayed in the debt-trap analysis that casts borrowing countries as victims, experts say – is that borrowers also have leverage and agency and can inflict costs on China. “The Chinese are lending to countries … in an over-exuberant way and getting burned,” says Dr. Brautigam. In 2018, for example, China had to restructure a loan to Ethiopia for a $4 billion railway linking its capital of Addis Ababa with Djibouti, extending the debt 20 years and taking a significant loss. Beijing has also restructured debt in Cameroon and Mozambique for projects that needed longer timelines to generate revenue.

The debate over Chinese lending is significant because developing countries face a huge shortfall in paying for the infrastructure they need. According to the Global Infrastructure Hub, the world will face a $15 trillion gap between projected and needed global infrastructure by 2040. While China’s investments are driven by its national interests, they also have potential to benefit the rest of the world, experts say.

And as China’s growth slows and debt at home threatens to cause economic instability, Beijing has signaled new limits on investments. At a symposium on the BRI last month, Mr. Xi called for China to strengthen its “early warning and assessment of the risks of overseas projects.”

Indeed, Beijing’s increasingly risk-averse posture will likely lead it to make more selective investments in the future, as it seeks a better balance between domestic and overseas lending, says David Lampton, a China expert and senior fellow at SAIS who has studied the BRI. Beijing also seeks to cooperate with other creditor countries and multilateral lenders to share the burden, he says.

“There are two sides to this story,” he says. “The Chinese view, at least in many quarters, is … we’re loaning to risky places. They can’t repay us. And we’re getting trapped with dubious assets.”

Often the push for Chinese investment comes from the recipient countries – as with the Southeast Asian railway project that the China-Laos line is part of, says Dr. Lampton, co-author with Selina Ho and Cheng-Chwee Kuik of “Rivers of Iron: Railroads and Chinese Power in Southeast Asia.”

Whose risk is it?

Southeast Asian nations have long held a vision of expanding and modernizing railroads to connect their economies and sought China’s help 20 years ago, only to be rebuffed then because Beijing was busy building its own road and rail infrastructure. “We have to ascribe the agency to countries around China – they’re not just victims,” says Dr. Lampton.

Today, China not only has the financing and technology to build the Southeast Asian rail network, but it also faces little competition for the business, he says. “It’s the lack of [comparable] alternatives for these countries that created dependence on China.”

In landlocked Laos, excluded from the maritime transport network that handles more than 80% of Southeast Asian trade with China, officials see the railway as the country’s best shot at fostering development.

Still, the risk of the China-Laos rail project is significant. Laos is already a heavily indebted country, with a public debt-to-GDP ratio estimated at 55% – with China’s share of that exceeding 10%. Last year, international credit rating agencies downgraded Laos to one notch above a rating of debt default, making it harder to borrow internationally.

If Laos can’t repay the $480 million loan for the project that it borrowed from China, which has a 70% stake in the railway venture, it is likely Beijing will have to absorb the loss, experts say. Beijing is willing to accept the risk of the Laos leg of the railway because it is the best pathway to the rapidly modernizing, middle-class economies of Thailand and Malaysia, experts say.

One tool China uses to mitigate the risks is to negotiate alternative revenue streams with host governments – for example revenue from mines and banana plantations in Laos, or the rights to commercial development along the railway, they say. China has struck similar deals in African countries including Kenya, where a tax on imports is used to help pay for a China-built railway, says Dr. Brautigam, director of the China Africa Research Initiative. “I see this as really creative [financing] rather than nefarious,” she says.

“Many of these projects are good ideas, but they may not be good in a short and strictly commercial time period,” she adds. “Some of them may be true white elephants,” but others “will be big contributors.”