Beijing is challenging global ‘rules.’ But some are pushing back.

Loading...

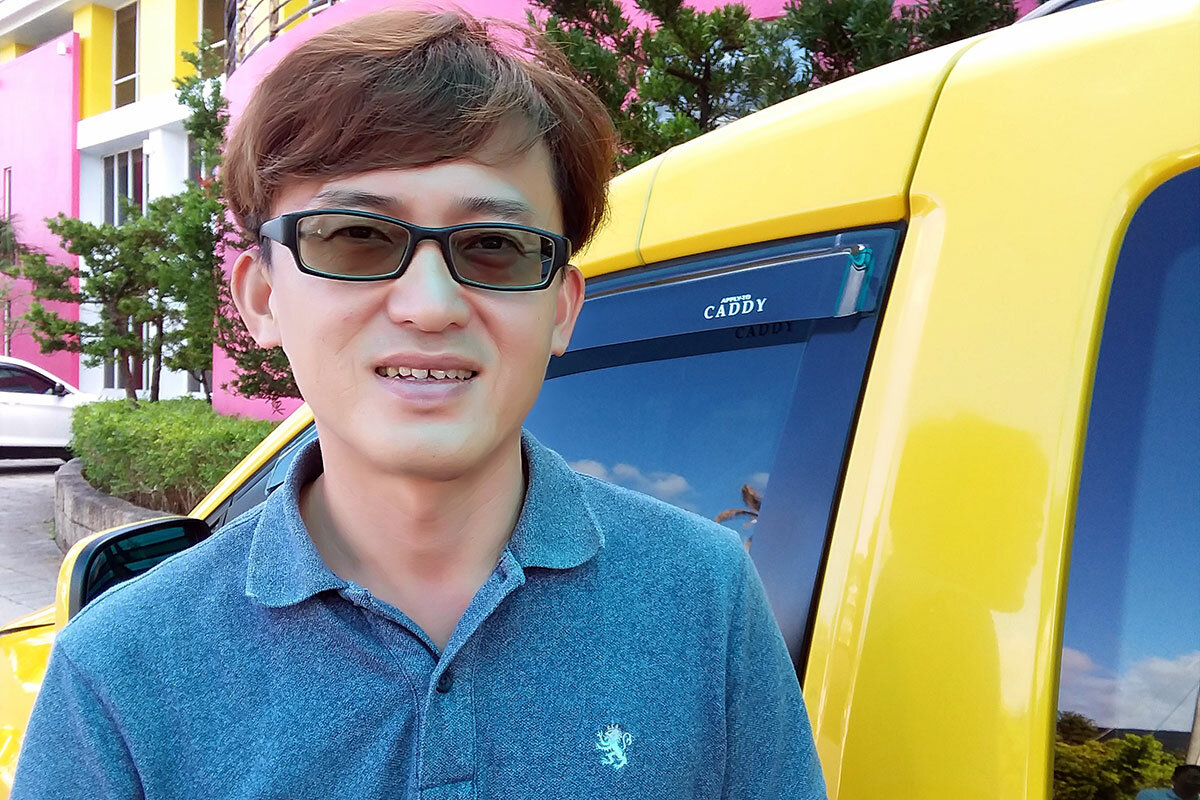

| Pingtung County, Taiwan

Liu Taiguang often walks along Taiwan’s windswept southernmost cape to the gleaming white Eluanbi Lighthouse, its beacon flashing from a fortified, cast-iron tower across the turquoise waters of the Bashi Channel.

A fourth-generation Taiwan native, Mr. Liu is as steadfast as this lighthouse near his home in supporting Taiwan’s independence. He is defiant in the face of Beijing’s insistence on uniting it with the mainland – by force if necessary. And he is jubilant that Taiwanese voters delivered a landslide reelection to pro-independence President Tsai Ing-wen in January, despite Beijing’s interference.

“Look at this election!” the wiry taxi driver says with a laugh. “Taiwan people won’t do whatever the mainland says.”

Why We Wrote This

When we say that the post-war order is in flux, what are we really talking about? Sometimes, it boils down to one word: China. But the questions Beijing’s rise has posed for people from Taipei to Washington are far more complex. Second in our global series “Navigating Uncertainty.”

Only 80 miles from the mainland, Taiwan has long been on the front lines of Chinese intimidation. Today, Taipei’s alarm – and readiness to push back – is shared in Washington and many other capitals, as China increasingly asserts itself as an autocratic economic, technological and military power following its own rules.

When China unleashed market reforms in 1979, Western leaders believed political liberalization would follow, bringing China into the fold of the international order that had held since World War II. But those expectations have unraveled since Chinese leader Xi Jinping took power in 2012, tightening the ruling Communist Party’s control and launching an ambitious program of “national rejuvenation” to achieve the “Chinese dream.”

Mr. Xi envisions China strengthening its sovereignty at home, projecting influence across Asia and beyond, advancing an authoritarian alternative to liberal democracy, and regaining a central place on the world stage – at a time when faith in democratic norms is shaky in many parts of the world. Beijing’s spending on foreign aid and development projects has soared, transforming the country into one of the world’s top lenders.

China is “fully confident in offering a China solution to humanity’s search for better social systems,” Mr. Xi proclaimed in 2016. In 2018, he said one of China’s priorities is “leading the reform of the global governance system,” which Beijing argues enshrines U.S. hegemonism and unfair trade and financial arrangements.

“What the Chinese government wants is to survive … to make a world safe for autocracy,” says Jessica Chen Weiss, an associate professor of government at Cornell University. “It’s in areas where the Chinese government has felt the most threatened by global norms, such as on human rights, that it has been the most determined to rewrite the rules to favor its interests.”

And Beijing is in a stronger position to do so at a time when the traditional institutions of global governance have atrophied, says William C. McCahill Jr., senior resident fellow at the National Bureau of Asian Research in Seattle. China is “working the [existing international] system for what it’s worth to them, and at the same time slowly building this kind of parallel universe,” he says.

Beijing stresses “win-win” diplomacy. But many governments are concerned that China often wields its wealth and power – including the world’s third strongest military – in zero-sum fashion, or out of sync with international norms.

The United States now casts China as a strategic rival, and President Donald Trump’s administration “has been enormously influential in shaping how the rest of the world now views China,” says Elizabeth Economy, Asia director at the Council on Foreign Relations.

In Asia, China is encountering resistance to its sweeping claims in the South China Sea. And some countries are reevaluating Mr. Xi’s signature foreign policy, a massive infrastructure plan called the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

Closer to home, “every element of Xi Jinping’s reunification narrative is being challenged, and that is at the heart of his ‘Chinese dream’,” says Dr. Economy. “China has come under enormous criticism for its human rights abuses in Xinjiang. In Hong Kong, there is really massive societal unrest … a rejection of the Chinese political model, and in Taiwan you had the reelection of Tsai Ing-wen.”

Taiwan’s defiance is extraordinary given the intense pressure Beijing exerts on the de facto independent island of 23 million people. Since President Tsai was first elected in 2016, China has cut off official dialogue, imposed economic sanctions, stepped up military actions, and bombarded the island with disinformation aimed at manipulating elections. Taiwan endures about 30 million cyberattacks a month, mainly from China.

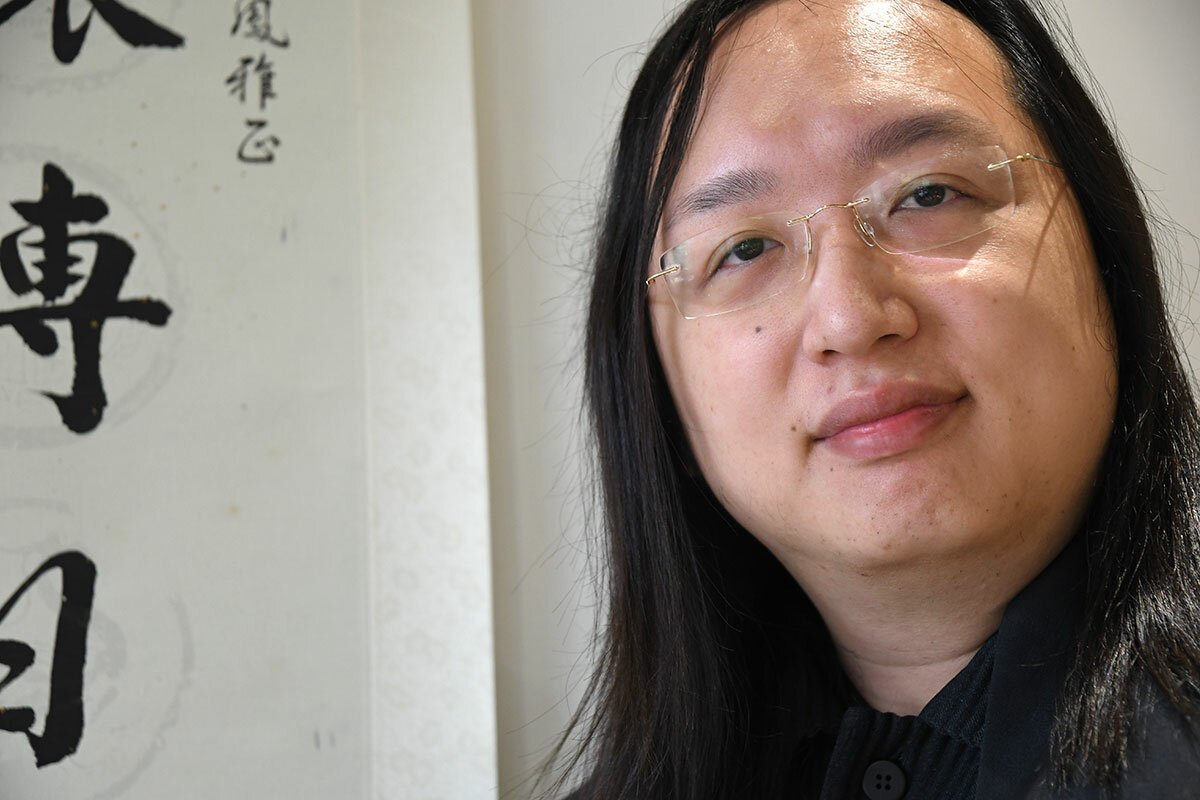

Digital Minister Audrey Tang says Taiwan’s “white hat hackers don’t have to do … drills, because they are facing real battles every day.” “Our democracy,” she says, “is battle-tested.”

Near the lighthouse, shops have lost business since China restricted mainland tourism to Taiwan. Mr. Wu, purveyor of fresh coconut milk, sells only half what he used to. “Taiwan is too small. We shouldn’t fight with the mainland,” he argues.

Overall, though, Beijing’s bullying seems to have backfired. Only one in ten Taiwanese today backs unification with China, and support for independence has more than doubled since 1995.

“China’s economy is huge and can allow us to make a lot of money, but democracy is more valuable,” says Mr. Liu, voicing a widespread sentiment. “You make so much money but you are not free? It’s very agonizing.”

As Mr. Liu visits the lighthouse one late January day, Chinese military jets conducting a drill roar over the Bashi Channel in a show of force designed to intimidate Taiwan. Mr. Liu is unfazed. “We are a free and democratic country,” he says. “We can’t tolerate a one party-rule, dictatorial country.”

Coercion at sea

Taiwan and many Asian states are feeling the heat from China’s burgeoning military, fueled by a defense budget larger than those of Japan, India, and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations combined.

Chinese fishing boats, coast guard vessels, and maritime militia are pushing ever deeper into the resource-rich and strategic waters of the South China Sea, regularly encroaching on the legal economic zones of the Philippines, Malaysia, Brunei, Taiwan, and Vietnam. Beijing’s claim to virtually the entire sea was dismissed by an independent international tribunal in 2016.

In January, a telling standoff near the Natuna Islands, which belong to Indonesia, highlighted how China’s seaward expansion is galvanizing a nationalist backlash.

A Chinese fishing fleet 1,000 miles from home, escorted by coast guard vessels, sailed into Indonesia’s Exclusive Economic Zone and fished for days without permission, ignoring a formal protest by Jakarta. The provocative move underscored China’s ability to conduct longer missions by resupplying vessels at bases it has constructed on artificial islands in the South China Sea – in violation of Mr. Xi’s 2015 pledge that China would not militarize the area.

But Indonesia’s President Joko Widodo pushed back. He dispatched fighter jets and warships to the Natunas, deployed hundreds of troops, and then landed there himself, saying Indonesia’s “sovereign rights” must be enforced.

The bold move worked. Soon afterward, the Chinese flotilla departed.

“China’s ultimate aim in the South China Sea is to have a veto over any activity,” so Indonesia’s rebuff was significant, says Brian Harding, deputy director of the Southeast Asia Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS).

As Indonesia, Vietnam, and other countries resist China’s encroachment, the United States is stepping up support with its “free and open” Indo-Pacific strategy. The U.S. Navy, still the most powerful in the region, staged a record number of “freedom-of-navigation patrols” in 2019 – aimed at keeping vital sea lanes open – defying Chinese navy warnings to stay out of waters it claims.

In a key step, the U.S. assured the Philippines last year that any armed attacks on its forces in the South China Sea would trigger their mutual defense treaty, although a bilateral spat is now threatening the alliance. A multiyear U.S. maritime security initiative is also underway to help Southeast Asian countries and Taiwan boost law enforcement and intelligence capabilities.

“It’s not just about keeping waters safe for navies to sail through. [South China Sea] resources are incredibly important to these countries,” says Bonnie Glaser, director of the China Power Project at CSIS. “We have to incur more risk.”

“China continues to flout international law” by laying claim to territories that do not belong to it, she adds. “If the U.S. does not stand up for the rights of smaller countries, then those countries will probably over time increasingly accommodate China ... because China is the big elephant right near them and the United States is far away.” But if the U.S., Japan, Australia, and other powers actively oppose China’s infractions, she says, smaller nations can strike a better balance.

The ‘Road’ to win-win?

If China’s military muscle-flexing is unnerving the rest of Asia, its major economic overture, the Belt and Road Initiative, has met with cautious welcome.

The initiative involves building an infrastructure network of roads, railways, pipelines and ports worth an estimated $400 billion to link China more closely to the rest of Asia and Europe. Its goals are to increase China’s access to energy and natural resources, open markets for Chinese goods, and secure China’s future growth.

But China’s failure to follow international norms in BRI projects has led to problems: Some borrowers – such as Sri Lanka – have found themselves with crippling debt burdens; BRI’s lax environmental standards threaten hundreds of species, activists warn; and opaque loan terms and project bidding procedures have fostered corruption. This has led some recipient countries to reevaluate their deals.

“Belt and Road has moved from being something that was overwhelmingly welcomed by the international community, to something that is still of interest but equally of concern, based on the way China is doing business,” says Dr. Economy.

In 2018, Malaysia’s then-Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad suspended a multibillion-dollar, 400-mile BRI railroad project, citing exorbitant costs and unfair terms. Mr. Mahathir then renegotiated the project, lowering the cost by $5 billion to $11 billion, securing a guarantee of 40% local participation, and reducing environmental harm.

“China may seem powerful – it’s got all the finances, the technology, the corrupt networks – but in the end the small countries in Southeast Asia have significant leverage over the Chinese,” says David Lampton, a China expert at Stanford University. “This idea that China is an unstoppable juggernaut, to which everybody else has to genuflect, is a mistake.”

The U.S., Japan, and India are stepping up funding, including through the new U.S. International Development Finance Corporation, launched in January with authority to lend $60 billion.

But if China dominates development lending to Southeast Asian nations, Beijing will easily enjoy undisputed influence, says Dr. Lampton, co-author of the forthcoming book “Rivers of Iron: Railways and Chinese Power in Southeast Asia.”

As China’s building spree races ahead, it will “change the face of Southeast Asia,” Dr. Lampton says. “The train has left the station. The question is, will we be on it?”

Today’s test case

In the heart of Hong Kong’s Central District, in a high-rise office suite lined with law books, Cambridge-trained Senior Counsel Alan Leong reflects on the pro-democracy protests that saw more than a million people flood the streets of the Asian financial center last summer.

“There has never been such an awakening of the Hong Kong people ... to the breaches of the Chinese Communist Party of Hong Kong law,” he says. The massive protests were sparked by a proposed extradition bill, later withdrawn, that would have allowed suspected criminals in Hong Kong to be sent to mainland China for trial in courts controlled by the Communist Party.

“Our personal safety was at stake,” Mr. Leong says. “We could feel for the first time the betrayal of trust. We had believed the Communist Party would honor the Basic Law,” he says, referring to the miniconstitution established to guarantee Hong Kong’s way of life and independent judiciary after the former British colony reverted to China’s sovereignty in 1997.

Hong Kong’s uncertain fate holds unique lessons for the democratic world, he says.

“We are a Chinese society on Chinese soil, flying the five-star red flag, but in every sense of the word, we are free,” says the bespectacled Mr. Leong, a former legislator and chairman of Hong Kong’s Civic Party. But Hong Kongers will have to go on fighting to preserve that, he adds.

Mr. Leong pauses, his look somber. “What I have been sharing with friends is: Today’s Hong Kong may be your tomorrow, and you have only yourselves to blame.”

Nearly 20 years ago the West made a mistake, he argues, by supporting China’s accession to the World Trade Organization, by believing China would adopt international legal norms, and by failing to police China’s compliance with those norms as it emerged as an economic giant.

Now, he says, democracies must uphold the rules-based international order against China’s challenges, just as people in Hong Kong are standing up for their core values.

“You are not just helping Hong Kong,” he says. “You are helping yourselves.”

You can find other stories in the Navigating Uncertainty series here.