In Hong Kong elections, the message is clear. The next step may not be.

Loading...

| Hong Kong

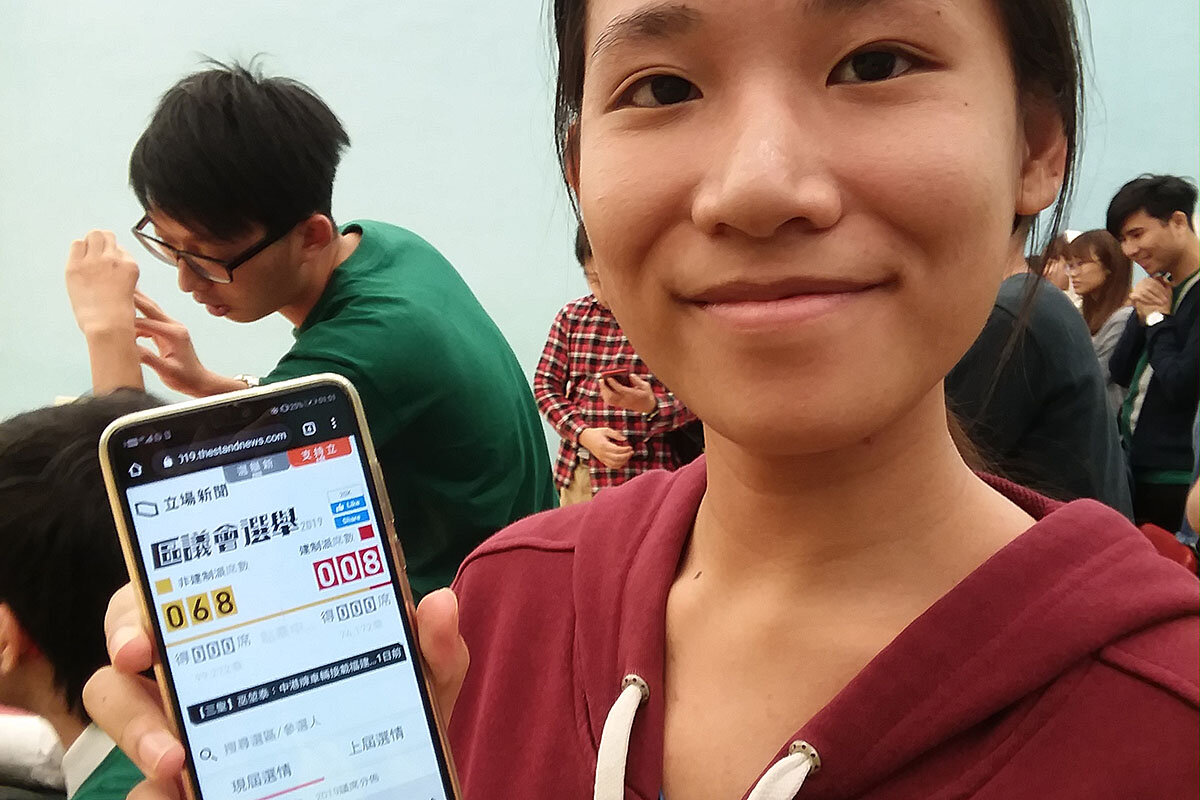

The Hong Kong vote-counting room was still packed with public observers at nearly 3:00 a.m. on Monday, when election officials named Fergus Leung the victor in the Kwun Lung district council race, eliciting celebratory cheers from the energized crowd.

Mr. Leung, a first-time candidate and university student, defeated an incumbent from a pro-Beijing party in a pattern repeated across Hong Kong in Sunday’s local elections, in which unprecedented numbers of Hong Kong voters rejected the pro-Beijing establishment and handed a landslide win to democrats.

“It’s a milestone in Hong Kong’s pro-democracy movement,” Mr. Leung said of the election, which drew a historically high voter registration of 4.1 million people and record turnout of 71%. Many view the election, which unfolded peacefully, as a clear public mandate for the protesters’ demands for greater autonomy and government accountability.

Why We Wrote This

Democracy just had a moment in Hong Kong, underscoring voters’ hopes for change after months of protests. But how does momentum toward shifting views – and policies – continue?

“The majority of Hong Kong people finally realize that democratization is the only way for Hong Kong in the future…and they really want to make a change,” said a smiling Mr. Leung, holding a bouquet of flowers from well-wishers.

Pro-democracy and independent candidates won nearly 400 of the 452 seats, giving them control over 17 of the 18 district councils. The pro-Beijing camp lost more than 230 district seats, including those of several high-profile lawmakers, while taking only about 60. Overall votes for both camps increased since the 2015 election, but the pro-democracy electorate was so large that some analysts describe it as a “tsunami.”

The strong sentiments at the polling stations matched those that have played out in Hong Kong’s streets for nearly six months. Mass protests erupted in the semi-autonomous Chinese territory in June over a proposed extradition bill that would have allowed some suspects to be sent to China for trial in courts controlled by the Communist Party. That bill was withdrawn in October, but protester demands have broadened to include an independent investigation of police actions, amnesty for arrested protesters, and universal suffrage.

“We want some change,” said Mr. Li, a teacher, upon leaving the polling station in Kwun Lung on Sunday night. “We want to fight for the [protesters’] demands.” (Mr. Li declined to give his full name.)

The councils are Hong Kong’s most democratic bodies, since its chief executive and half of its legislature are not directly elected – making the democrats’ win symbolically powerful. But representatives may face an uphill battle turning their victory into meaningful reform.

‘A window of opportunity’

In response to a stark election rebuke that many analysts described as a referendum against Hong Kong’s leadership, Chief Executive Carrie Lam issued a statement saying her government “will listen to the opinions of members of the public humbly and seriously reflect.”

Critics, however, said a more tangible, positive response is required from Mrs. Lam as well as her superiors in Beijing. “If they misjudge the situation again” and resort “to heavy use of police force against the protesters, they are inviting a new round of confrontations,” says Kenneth Chan, associate professor and director of the Comparative Governance and Public Policy Research Centre at Hong Kong Baptist University.

“This is a window of opportunity, a turning point possibly for [Mrs. Lam] to steer her way out of this political crisis,” by offering concessions to de-escalate the deadlock and end clashes between police and protesters, Professor Chan says.

Pro-democracy party leaders agreed.

“Given the results of yesterday’s elections, there is really no excuse for Carrie Lam not to accede to the five demands” of the protesters, says Alan Leong, chairman of Hong Kong’s liberal democratic Civic Party, which ran 36 candidates in Sunday’s elections and won 32 seats – the most ever for the party.

One immediate, minor concession Mrs. Lam could make, Mr. Leong says, is to order the police force to end its siege of The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, where dozens of student protesters are surrounded and in hiding following a weeklong standoff. (On Monday, police announced they would enter the campus to negotiate, but not arrest students on the spot, as concerns grow about their well-being.)

Ultimately, Mr. Leong and other democrats say, Mrs. Lam should personally take responsibility for the rock-bottom trust in her leadership and government, as shown by public opinion polls and Sunday’s election results, and step down.

Analysts, however, generally agree that Mrs. Lam must follow directions from Beijing. “Our autonomy has been eroded to such an extent that the chief executive of Hong Kong could not say more [about the elections] than ‘OK, noted with thanks,’” says Professor Chan. “Clearly, she is waiting for instructions and orders from Beijing to plan her next moves. That is the reason she has lost any credibility in the eyes of the Hong Kong people.”

The election defeat is a setback not only for Mrs. Lam but for Beijing’s assertion that most Hong Kongers are a “silent majority” that support the government. China’s state media did not comment directly on the election outcome, but repeated calls for restoring order and opposing foreign interference in Hong Kong.

New kids on the block

For its part, the newly elected grassroots pro-democracy candidates must overcome challenges of relative inexperience and loose organization, analysts say. “It’s a huge learning curve. These newly minted politicians are very young,” says Stan Hok-Wui Wong, a social scientist at The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, who researches Hong Kong’s elections. “I have two current students elected.”

Hong Kong’s 18 district councils are advisory bodies without substantial policymaking power. But they deliver funds for cultural, environmental, and other community activities, and in that way develop a base of political support. Winning the majority of district council seats significantly increases the democrats’ leverage in the 1,200-strong committee that elects Hong Kong’s chief executive.

A bigger issue is the lack of a unified organization – both among new candidates who emerged from Hong Kong’s fluid, leaderless protest movement, as well as among traditional opposition parties. “The lack of coherence has plagued [the opposition] for decades,” Professor Wong says. “No one has a magic formula for solving it.”

Such coordination will be vital for the democratic camp to translate their local election gains into more seats in Hong Kong’s lawmaking body, the Legislative Council, in elections scheduled for September 2020.

As they stepped out of the polling station into the narrow, winding streets of northwestern Hong Kong’s Kennedy Town neighborhood on Sunday night, many voters said they welcomed the chance to make themselves heard with ballots.

“This is very peaceful, no blood, no fire, and can tell everyone what Hong Kong people support,” says Mrs. Chen, a pro-establishment voter who says she thinks democracy is important but worries about the risks Hong Kong’s youths face in the streets.

Down the block, Mr. Yam, a recent engineering graduate, says a victory at the polls could “slow down the protests” by electing local officials who can voice popular demands to the government. (Mrs. Chen and Mr. Yam declined to give their first names.)

The democrats have pledged not only to push forward protesters’ aspirations, but to “get down to the business of revamping the system of governance from the bottom up,” such as by breaking up pork barrels, Professor Chan says.

Raising his arms and pumping his fists in the air moments after his victory, Mr. Leung, a medical student, promised to contend for Hong Kong people on all fronts. “I hope that we can really do a great job and show people that other than fighting for democracy, we can also take care of the residents properly in the next few years.”