Tiananmen 30 years later: ‘Hope has not died,’ say Chinese dissidents

Loading...

| Sacramento, California

At his house in a tree-lined subdivision south of Sacramento, dissident journalist Zhang Weiguo sips green tea as his gray-haired mother dishes up a steaming bowl of homemade Shanghai wonton dumplings – a fragrant reminder of a long-gone place and time.

In Shanghai, the narrow lane where Mr. Zhang grew up has been bulldozed to make way for a skyscraper. The World Economic Herald, the semi-independent Shanghai newspaper where Mr. Zhang was a lead reporter, was shut down by the government in 1989 – its outspoken brand of journalism absent from China today.

“My dream has been crushed,” Mr. Zhang says slowly, his words oddly out of place at this kitchen table, overlooking a sunbathed backyard garden of leafy cucumber vines and beans. But, he adds, “hope has not died.”

Why We Wrote This

The brutal crackdown after the Tiananmen massacre froze China’s pro-democracy movement. But conversations with three exiled dissidents underscore how those protests continue to inspire activism and the expectation of eventual change.

Thirty years ago, Mr. Zhang was among the young intellectuals and activists leading the boldest movement for democracy ever seen in communist China. Protests calling for free speech, press freedom, and democratic reforms engulfed Tiananmen Square – the symbolic center of power in the capital, Beijing – then spread to dozens of major cities nationwide.

But after several weeks, Communist Party hard-liners prevailed over reformers, and paramount leader Deng Xiaoping ordered the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) into Beijing to crush the demonstrations and clear the square. On June 3 and 4, 1989, troops with tanks pushed into the capital, opening fire with machine guns on civilians. Estimates of the number killed range from hundreds to several thousand. The crackdown effectively silenced advocates of political reform within China’s leadership.

Jailed by the regime as a “black hand” and forced into exile, Mr. Zhang and other banned dissidents have sacrificed greatly for their ideals. Yet they remain keen observers of China today. Despite the country’s repressive trajectory – intensified since President Xi Jinping took power in 2012 – Mr. Zhang and other prominent Tiananmen-era activists believe Chinese aspirations for basic rights are growing under the surface, and will eventually emerge again.

Mr. Zhang feels fortunate to have been part of the push for media independence in the 1980s – a golden era for maverick publications, in contrast to today.

“The level of control over the media in China under Xi is the tightest it has been since right after the 1989 crackdown,” says Mr. Zhang, who has continued to write and edit for overseas Chinese-language newspapers and magazines. “Xi doesn’t want Western-style liberalization,” and is following the example of Mao Zedong, who believed “the Communist Party’s two legs are the pen and the rifle – public opinion and violence,” Mr. Zhang says.

For China’s current leaders, the lesson from Tiananmen is simple, Mr. Zhang says: “Suppress the Tiananmen movement and kill however many people, and the country will be stable for decades. This is China’s model: suppression.”

China is now moving aggressively to export its ideology and propaganda, through global and local television networks, newspapers, and other media that are widely available in U.S. markets from Los Angeles to New York, he says.

Social media, however, offers one realm in China today where limited expression is possible, Mr. Zhang says – despite the efforts of China’s army of censors and official commentators. “There’s a joke: If you watch the daily official news broadcast, you would think nothing’s happening in China. But if you go on the internet, you will think China is about to collapse. So there is some space, a growing diversity of voices, and it is on the web.”

Mr. Zhang has jumped into that space, writing a blog that helps capture China’s independent online voices before censors can delete them, and sharing them with outside audiences. Despite severe setbacks for freedom and democracy over the past 30 years, he believes that “in the end, China will have to return to that track.”

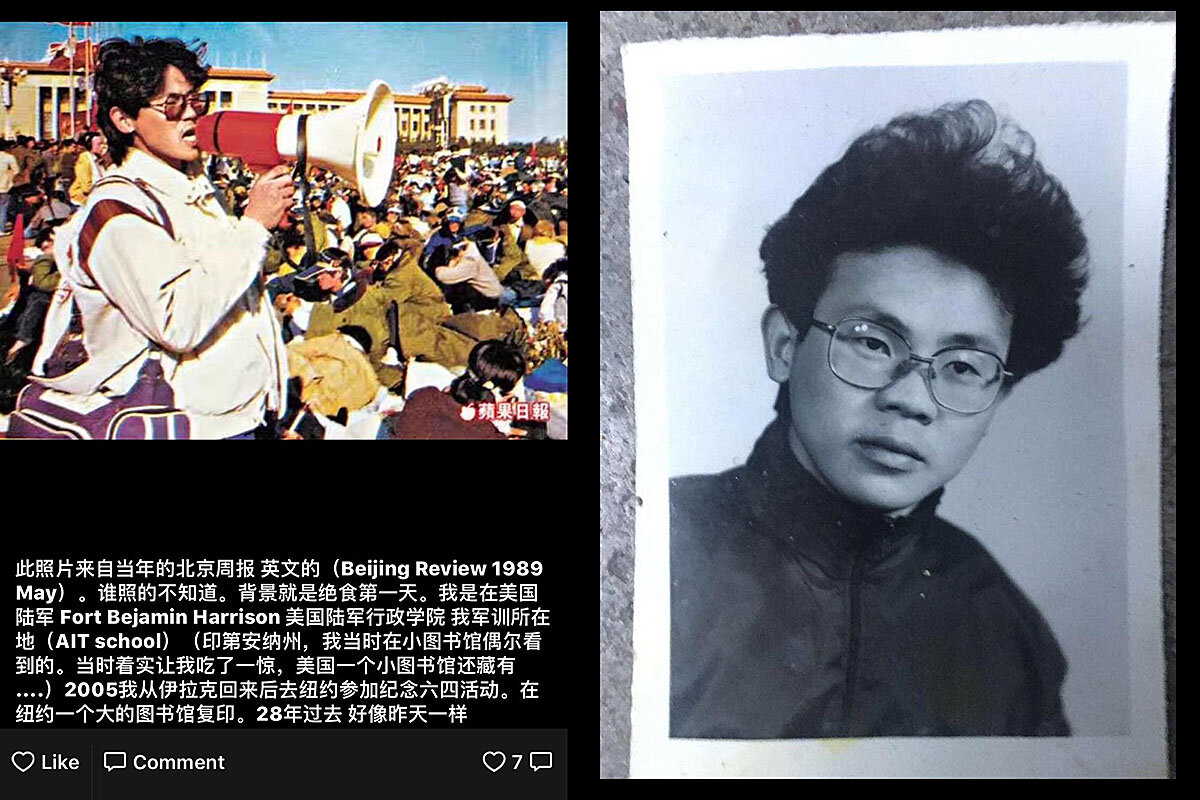

Maj. Yan Xiong

For U.S. Army chaplain Maj. Yan Xiong, his Memorial Day remembrances extend from the chapel at Fort Huachuca, Arizona, to the desert battlefields of Iraq and beyond, to Beijing.

Major Xiong offers prayers not only for fallen U.S. soldiers who served with him on the outskirts of Baghdad in 2004, but for the Chinese civilians he saw gunned down by the PLA in Beijing in June 1989.

Then an idealistic Beijing University law student, Xiong helped lead demonstrations in Tiananmen Square, watching in awe as the crowds swelled.

“Even after 30 years, the number one impression in my mind is the millions of people. ... The whole society supported that democratic movement,” he recalls. He helped organize an independent student council and took part in student dialogues with government officials.

Hearing reports of PLA troops opening fire, he and a friend rushed toward the square. “I witnessed a massacre, and I still cannot forget that. I even carried a lot of bodies to the hospital,” he says.

After the crackdown, Major Xiong and other student leaders wanted by the government scattered to other provinces as part of a plan to rekindle the movement outside Beijing. Arrested in northern China at gunpoint, he was jailed for 19 months. Released in 1991, he felt betrayed and empty.

Then, a friend from an underground Christian church gave Major Xiong a book that would change his life: “Streams in the Desert,” a 1925 devotional by a Christian missionary who had worked in China. Major Xiong read the thin volume every day on walks near the old Summer Palace north of Beijing.

“It made my heart warm,” he recalls, though back then he could not articulate why.

Escaping China on a fishing vessel to Hong Kong, he gained political asylum in the United States in 1992. There, he joined a church and was baptized, one of several Tiananmen activists drawn to Christianity. He enlisted in the U.S. Army and later graduated from seminary and was commissioned as an Army chaplain.

Today, Major Xiong sees a direct connection between the disillusionment with communism in China and the rapid growth of Christianity there.

“In China, more and more people are disappointed with the reality,” he says. “They need something that can comfort them so they can have hope for the future.”

To the atheistic party, this trend seems threatening.

“In China when a person says, ‘I am a Christian,’ it means ‘I will follow Jesus, not the party,’” he says.

China has barred Major Xiong from returning, even to visit his ill mother, who died in 2015.

Major Xiong worries the party’s rigid rule will see problems build without solutions – threatening the regime with eventual collapse. In such a crisis, he hopes the PLA would not repeat the mistakes of Tiananmen.

“The PLA is not the military of the party, they are the military of the Chinese people,” he says. “They belong to the people and should stand on the right side.”

Han Dongfang

From a high-rise office on Hong Kong’s Kowloon Peninsula, labor activist Han Dongfang launches into another interview with a disgruntled Chinese worker about why he went on strike.

“So, in all your years as a road worker, the [state-run] trade union never came to help you?” Mr. Han asks in his rapid-fire Beijing accent.

“No, I’ve never heard of it,” the worker replies.

During his weekly, Mandarin-language broadcast on Radio Free Asia, Mr. Han airs the grievances of Chinese workers struggling with pay, safety, health, and other workplace challenges across China. The conversations are part of Mr. Han’s lifelong fight for labor rights and democracy.

As a railway worker, Mr. Han helped create China’s first independent labor union, the Beijing Workers’ Autonomous Federation, during the Tiananmen protests. Rallying workers behind the students, Mr. Han and the BWAF became top government targets after the June 4 crackdown.

Holding fast to his convictions, Mr. Han turned himself in and was jailed for almost two years before gaining release in 1991 for medical care in the U.S. He returned to China briefly in 1993 only to be immediately expelled to Hong Kong, where he founded the China Labor Bulletin (CLB), a nongovernmental organization defending workers’ rights.

Today, Mr. Han is encouraged by Chinese workers’ growing willingness to stand up for themselves – demonstrated by widespread labor strikes across the country. An online map maintained by CLB tracks details of hundreds of strikes, sit-ins, and other labor actions unfolding in China, including some 600 so far this year. The government censors news on strikes, but word of the incidents often spreads on social media.

Despite the government’s recent arrests of labor activists and tightening of controls on NGOs, Mr. Han says individual workers’ consciousness is what matters in the long run.

“They don’t put their hopes in the government or other people, but in themselves – this is far beyond what we could imagine 30 years ago,” he says. “If you have awareness of your rights … and how to fight … this is where the hope is.”

As China’s unbridled, profit-driven growth has given rise to growing inequality, corruption, pollution, and health and safety issues at workplaces, Mr. Han says, the government is incapable of safeguarding worker rights on its own.

“The Chinese communist government realizes it can’t stay in power unless they satisfy the working families in China,” he says. China is one of the world’s most unequal countries as the income gap between urban and rural grows, according to the International Monetary Fund. “One of the biggest legitimacy issues they are facing is wealth redistribution.”

As a result of these tensions, Chinese workers will steadily gain power, Mr. Han predicts, starting with access to collective bargaining for better conditions. “That will lay a very solid ground for a social democratic solution in China,” he says.

Close to the pulse of workers through his regular radio talks, Mr. Han is optimistic about China’s future. “I believe, based on reality and also hope, that the best way out is for China to turn to social democracy, and become the world’s biggest democratic regime.”