As China clamps down, internet users find it harder to scale 'Great Firewall'

Loading...

| Beijing

A chill wind whips down the walkways on the campus of Peking University, the selective academy that attracts China’s best and brightest students. Strolling past the stone steps and upturned roof of the university library, a law student vents about how China’s ruling Communist Party is tightening controls on information.

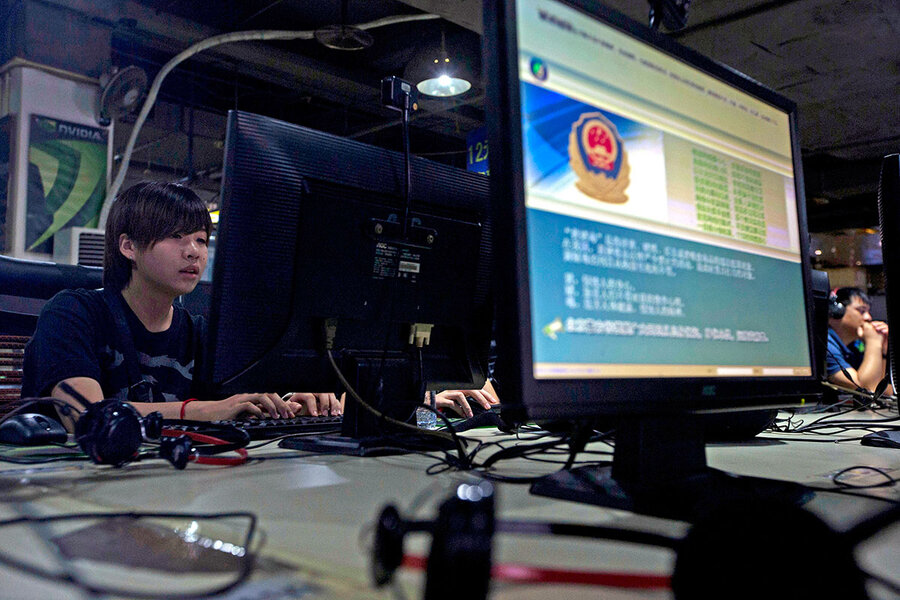

“It’s harder this year than last year” to bypass the firewall that government censors use to block thousands of blacklisted websites, says the student. (Her name, like others in this story, has been omitted for privacy.) “A lot of VPNs [virtual private networks] are prohibited now,” she says, referring to the technology many students use to fanqiang, or “jump the wall.”

Jumping the wall has grown more difficult under President Xi Jinping, amid an overarching strengthening of Party control. Over the past year, Beijing has moved to restrict the availability of VPNs, including by prosecuting Chinese businesspeople who sell VPN software. This week, a Shanghai court gave a Chinese software developer a three-year suspended sentence for operating a website selling VPN services in China.

Why We Wrote This

China has more internet users than any other country. And as its online censorship tightens, the consequences may ripple beyond its borders.

The “Great Firewall,” China’s digital censorship technology, summons up images of an impenetrable fortress. The firewall blocks foreign news, search engines, and social media, creating a buffer against information that goes against the party line. In reality, that wall has had significant gaps, largely thanks to VPNs. Today’s nationwide crackdown represents an attempt to close one of the biggest remaining loopholes through which ordinary Chinese can gain access to the world of unfettered information.

“Internet media should spread positive information, uphold the correct political direction, and guide public opinion toward the right direction,” the state-run Xinhua news service reported in April, summarizing the instructions of Mr. Xi, who “stressed the centralized, unified leadership of the Party over cybersecurity.”

China’s dogged pursuit of online censorship challenges the belief that a digitally connected society will inevitably be a freer one – and sets an example for other nondemocratic regimes, experts say.

“China’s censorship system has become the model for many authoritarian regimes: evidence exists that others are trying to emulate it,” political scientist Margaret Roberts writes in “Censored: Distraction and Diversion inside China’s Great Firewall.” In the era of digital media, China’s manipulation of public information also raises issues relevant for democracies, Professor Roberts argues, such as the need for corporate transparency about the algorithms behind online searches.

In Beijing’s northwestern Haidian District, home to most of the city’s universities and historically a center of intellectual ferment and debate, students say they are feeling the impact of the crackdown. While all the students interviewed say they can still skirt the censorship wall, they agreed it is growing more difficult.

“The VPNs are not stable. I often have to change from many kinds of VPN to get access now,” says a history student from Peking University, taking a break from studies in a café. “It’s a very serious problem. In our country, those in power limit the information that the society can have.”

Eyes on 800 million

China already has the world’s largest and most sophisticated censorship apparatus, reaching far beyond banning and dictating content at traditional state-run media such as newspapers and television stations. The government employs thousands of censors to monitor, filter, and delete posts it deems unfavorable on social media, while fabricating an estimated hundreds of millions of pro-government propaganda posts each year, according to experts. Meanwhile, the firewall blocks thousands of websites including Google services, foreign news outlets, and social media such as Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter.

Yet the sheer scope of online activity by China’s population – currently with some 800 million internet users, according to the China Internet Network Information Center – makes this a daunting task.

Indeed, experts say China’s censorship regime has operated less like an impervious wall than a seepy, complex ecosystem, with the government applying varied pressure depending on the size and nature of the leaks.

“In China, censorship is porous and penetrable,” says Roberts, an associate professor of political science at the University of California, San Diego.

Chinese with the time, money, and motivation have still been able to obtain VPNs to jump the firewall. Only a small percentage do, and they tend to be younger, wealthier, and better educated, and to live in cities along China’s coast, Roberts says.

Taking a two-pronged approach, the government assumes most Chinese are impatient and indifferent to sensitive topics, and so uses indirect methods to nudge people away. These include throttling websites to make them load slowly, censoring keywords, burying search results, and distracting citizens with propaganda posts. In contrast, authorities generally reserve the harshest censorship and fear tactics – including detention and prison – for a relatively small group of political and social activists, such as human rights lawyers, outspoken bloggers, and journalists.

Cracks in the system

Still, the strategy has risks. Popular indifference can evaporate during a crisis, causing a censorship system based on apathy to fail when the government needs it most, research shows.

When pro-democracy demonstrations erupted in Hong Kong in 2014 over electoral system interference by Beijing, for instance, China’s censors worried the protests would spread to the mainland, and blocked the social networking service Instagram. That backfired immediately, inspiring millions of Chinese users to obtain VPNs, join censored websites such as Twitter and Facebook, and follow news about the Hong Kong protests.

More recently, when students from several universities in China rallied behind a group of factory workers seeking to unionize in China’s southern city of Shenzhen this summer, censors were unable to stop the word from spreading.

“It takes time for the government to delete information from Weibo, so by then many people already know about it,” says a physics student, wearing a maroon and white Peking University letter jacket. Weibo, a popular Chinese social media platform, requires users to register their real names, and posts with sensitive content are blocked or deleted.

Students are not the only ones concerned about heightening restrictions on information access, according to interviews with several Beijing workers and shopkeepers.

“There are a lot of ordinary people who are curious to see China from the outside. They want to jump the wall,” says the owner of a dress shop near Beijing’s main downtown train station. Ordinary citizens are well aware of the censorship, she says.

“If you post anything sensitive on the web, you will be shut down. Your WeChat number will be blocked,” she says, referring to a popular Chinese messaging app. “It has happened to my friends.”

Foreign businesses rely extensively on VPNs for their operations, but so do some Chinese firms. Chinese social media companies sometimes ignore censorship policies that hurt their bottom lines or make them less competitive, preferring to incur fines, experts say.

“Market competition can lead media companies to push back against state directives,” Blake Miller, a postdoctoral fellow at Dartmouth College in New Hampshire who studies Chinese politics, writes in a working paper. In a study using leaked data, Dr. Miller found that Weibo disobeyed about 1 out of 6 government directives, motivated by the company’s concern about alienating customers by censoring more strictly than its Chinese social media competitor, Tencent.

All this suggests that the government’s bid to strengthen censorship will face ongoing resistance.

For some of China’s most talented students, opposition could take the form of leaving the country.

“I don’t like the world that the government builds for us, one that decides what we see and what we believe,” says a Russian language student. After graduation, he plans to head to Moscow.