Great game: Polls in Pakistani Kashmir smooth way for epic China pipeline

Loading...

| Gilgit, Pakistani-controlled Gilgit-Baltistan

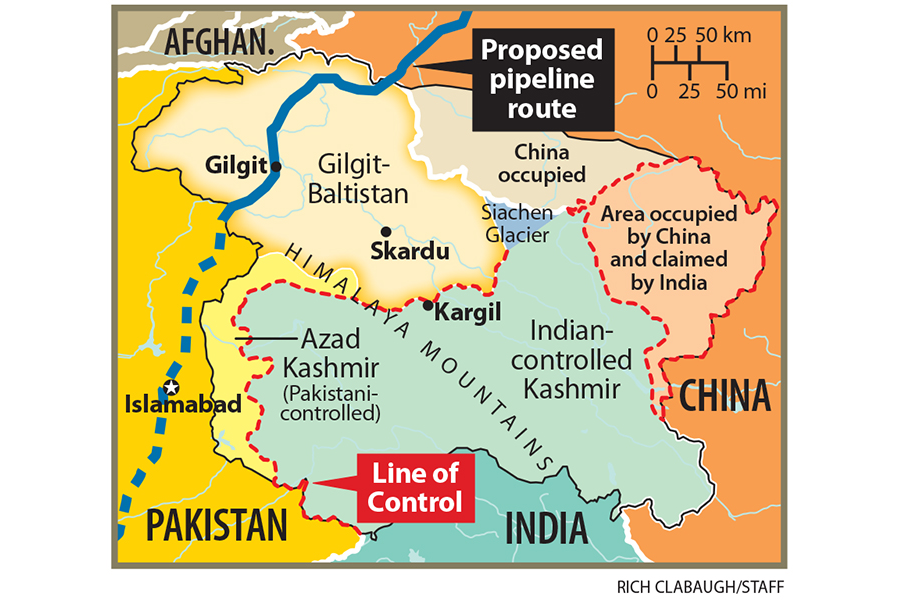

Pakistan’s disputed Gilgit-Baltistan region, located above India’s Kashmir Valley and the site of a bitter war between India and Pakistan in the late 1990s, is today ground zero for a pending China pipeline to the Indian Ocean – a $46 billion project that represents Pakistan’s largest-ever foreign investment.

It was also the site of elections earlier this month that saw Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif's Pakistan Muslim League take a majority in the 24-seat assembly.

Pakistan says the election results will provide the necessary stability to keep the pipeline deal on track. But for India, both the elections and the pipeline corridor have aroused suspicion about a region that has become a linchpin in a China-Pakistan alliance often regarded as hedge against India.

The victory came after last fall's elections next door in Indian-controlled Kashmir, where the Hindu nationalist party of Indian President Narendra Modi won enough seats to form a ruling coalition in territory long disputed by Pakistan.

But the Indian Ministry of External Affairs took a dim view of the vote, issuing a statement prior to the election calling it “an attempt by Pakistan to camouflage its forcible and illegal occupation of the region.”

In many ways, the jockeying for position, leverage, and power in Gilgit is the latest iteration of the “great game” in this part of the world. India, Pakistan, and China have long vied for this mountainous crossroads territory that connects Central Asia to South Asia.

The mountainous area of 2 million people borders Afghanistan to the northwest, China to the north, and Indian-controlled Kashmir to the east. Gilgit-Baltistan's glaciers, the largest outside the polar caps, are the source of water for the Upper Indus Basin, which provides water for most of the Indian subcontinent.

Elections this month are part of an effort to solidify Pakistan’s hold on Gilgit, which has seen a rise in calls for autonomy. Before the elections, Pakistan detained 41 pro-autonomy activists and charged them with sedition. The elections are also seen as a way to smooth the deal with China.

In April, Chinese President Xi Jinping visited Pakistan and signed a series of memorandums on future economic projects in the pipeline corridor, which runs through Gilgit to connect the ancient city of Kashgar in China’s Xinjiang Province with the Pakistani port of Gwadar on the Arabian Sea.

The $46 billion figure is more than any US aid package and includes hydroelectric dams, a liquid gas pipeline, and the rebuilding and expansion of the Karakoram Highway that will cut directly through Gilgit.

When President Modi visited to China this May, New Delhi issued a statement calling the pipeline project “unacceptable.”

These are the second set of elections since 2009, when Islamabad passed a law changing the region’s name from the Northern Areas to Gilgit-Baltistan. The Gilgit region was granted nominal self-governing authority. That means the local assembly can pass laws, but it has no control over issues like its budget or trade with neighboring China.

That authority rests with the “Gilgit-Baltistan Council,” a body headed by Mr. Sharif and dominated by his cabinet.

“Pakistan has not given us rights like a province,” says, Adnan Malik, a shop owner in Gilgit, “so I voted for the PML-N, since they are in power [in Islamabad].”

Gilgit-Baltistan is roughly the same size as neighboring Kashmir, which Pakistan and India have fought three major wars over since independence from Britain. Islamabad agrees the region is disputed territory, along with Kashmir; Pakistan's Constitution makes no mention of Gilgit-Baltistan.

Soon after independence in 1947, locals in Gilgit-Baltistan, a majority Muslim region, wrestled control from representatives of the Srinagar-based Hindu Maharaja, who turned his kingdom over to India.

In 1962 New Delhi fought a war with Beijing in 1962 over a part of Kashmir just east of Gilgit-Baltistan. In 1963, Pakistan and China inked an agreement that saw part of the disputed region ceded to Chinese control. Soon after, the two nations began work on the Karakoram Highway, the world's highest paved road, which connects the Chinese province of Xinjiang with Gilgit.

The region is dotted with memorials to fallen soldiers, thousands of whom have died in several attempts by Pakistan to take territory from neighboring Indian-controlled Kashmir.

Hundreds of locally recruited troops have died in ongoing battles with India for the Siachen Glacier, in the east of the region.

In 1999, hundreds more died in an attempt by then- Gen. Pervez Musharraf to take the town of Kargil, just across the Line of Control, which serves as the de facto boundary between Pakistani and Indian-controlled Kashmir.