Why did China just release five feminist activists?

Loading...

| Beijing

Sidestepping a snowballing international public relations disaster, China on Monday evening freed five women who had been detained since early March for organizing a campaign against sexual harassment.

Their fate had drawn widespread attention at home and criticism from US officials and human rights groups. Advocates for the women say this external pressure paid off with their release after the prosecutor decided not to press charges. China is preparing to co-host a United Nations meeting on women’s rights in New York in September.

Still, such campaigns can backfire since China is generally reluctant to bow to public pressure. International protests against the trials of 2010 Nobel Peace Prize winner Liu Xiaobo and later of Ilham Tohti, a prominent moderate advocate of Uyghur rights, did nothing to save them from heavy jail sentences.

“Those were political cases,” says Liu Xiaoyuan, a lawyer for artist-provocateur Ai Weiwei who was detained for nearly three months in 2011. “If a case is related to national security it is treated differently from a case about something like women’s rights.”

Mr. Ai was freed after a noisy international campaign on his behalf by world-renowned cultural figures. “His detention really changed attitudes to China among a huge number of influential people,” says Jerome Cohen, a law professor at New York University who follows Chinese legal affairs closely. “The government learned its lesson” when it comes to cases not deemed to directly involve national security.

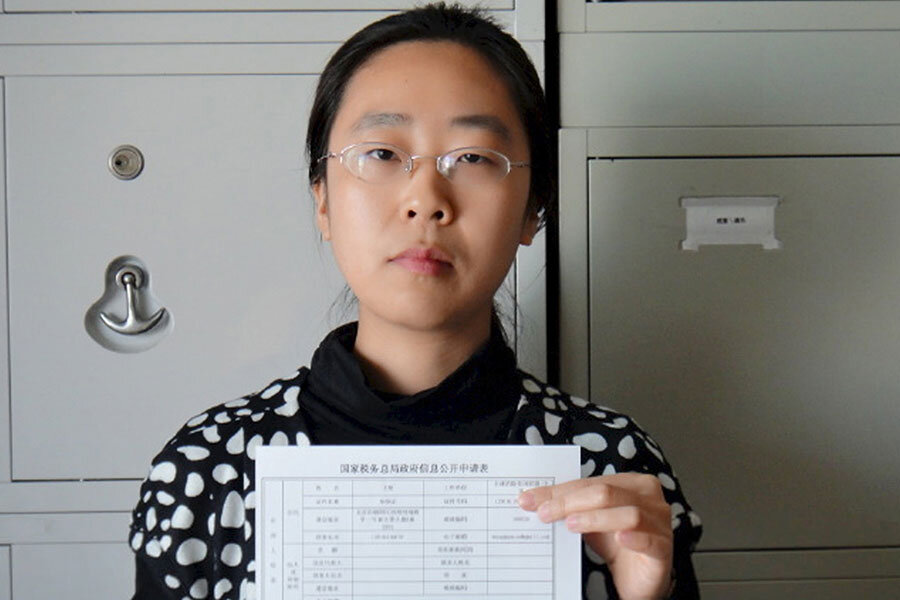

The five young women, all experienced activists with a reputation for staging imaginative public “happenings” to draw attention to violations of women’s rights, had been planning a leafleting campaign against sexual harassment on public transport to coincide with International Women’s Day on March 8th .

They were detained the day before on pre-emptive charges that they had been “picking quarrels and provoking trouble,” which carries a maximum five-year jail sentence. Their arrests came before they could do anything. The police then changed the charge to “gathering crowds to disturb public order” referring to two “happenings” carried out in 2012. The prosecutor appears to have found insufficient evidence for that charge too.

“This is largely a result of external support,” says Wang Qiushi, one of the women’s lawyers. “The appeals from foreign political leaders and women's rights groups played a very important role in the release.”

Calls from abroad

Last Friday, US Secretary of State John Kerry urged the Chinese authorities to “immediately and unconditionally” free the women. Hillary Clinton also denounced their detention.

“This is a case where internal and external public opinion has played a role,” says Mr. Cohen. “Without it they would certainly have been prosecuted.”

At the same time, adds Mr. Wang, “the women did not commit any crime so they should not have been detained in the first place.”

Women’s rights activists welcomed their release. “The unprecedented huge mobilization of global feminist and other non-governmental organizations’ support is effective,” wrote Wang Zheng, a professor of women’s studies at the University of Michigan, in a post on ChinaChange.org, a pro-democracy website.

Ms. Wang also drew hope from signs that “the Chinese government is not a monolithic entity and the decision is a compromise between different political factions … there were officials in the system who pushed very hard towards a positive solution.”

UN women's meeting

As well as international opprobrium, domestic public pressure can also be effective in China. In 2010, Deng Yujiao, a young woman working in a pedicure parlor, was initially charged with murder for killing a government official who had tried to force himself on her. The charge was dropped after nearly four million people expressed their sympathy for her on social media.

The case of the five detained feminists was especially embarrassing internationally because China is due to co-host a UN meeting in September, marking the 20th anniversary of the fourth world conference on women held in Beijing in 1995. Mrs. Clinton, then First Lady, now presidential aspirant, delivered a forceful speech on feminism and human rights at that conference.

In a letter to the prosecutor, the five women’s relatives wrote that their detention was unjustified because they had been acting “in line … with our law for the protection of women and children and with the core values of socialism.”

The women were not freed unconditionally, but on bail. Their bail conditions are not yet known, but will restrict their freedom of movement and action and could prevent them from communicating amongst themselves for up to a year while the police continue their investigation.

Given their history of activism, however, those who know the women say they do not expect them to stay silent. “Wei Tingting will decide what to do,” Wang said of his client. “But I personally do not think she will give up.”