Shakespeare in Shanghai? The Bard takes China by storm

Loading...

| Beijing

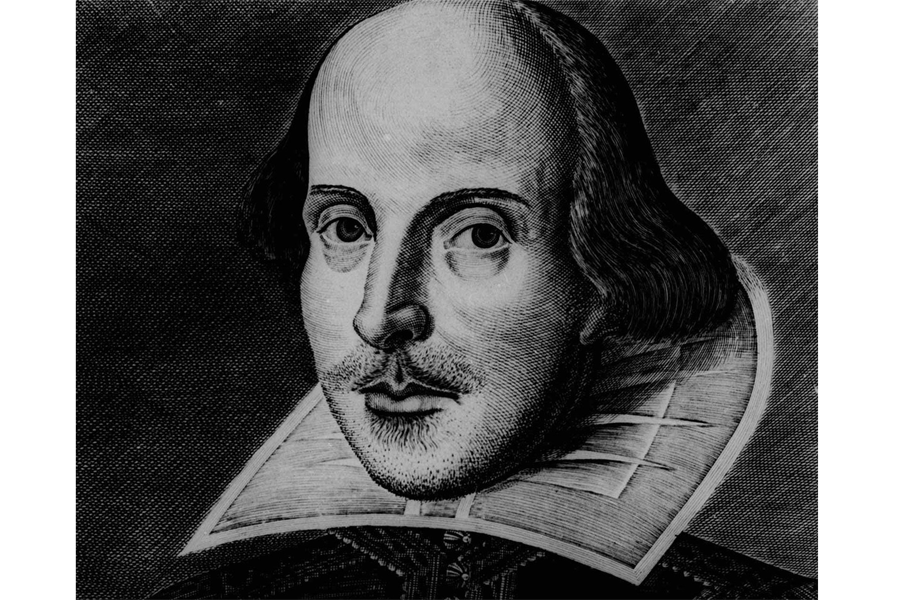

When it comes to Great Britain’s soft power armory, William Shakespeare counts as heavy artillery. And London is rolling him out on the far shores of China these days in repeated cannonades.

In Beijing last weekend, Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre ended a sold-out China tour of “A Midsummer Night’s Dream.” A Chinese publishing house is now nearly finished compiling the Bard’s works in a scholarly new Mandarin translation. Moreover, the British government has just announced a $2.4 million project to launch a brand new “Collected Works” of Shakespeare translated specifically for today’s Chinese stage.

“Shakespeare is one of our greatest cultural exports, beloved in China as well as here,” British Finance Minister George Osborne said as he announced the new translation grant to the Royal Shakespeare Company in September.

And that translates into hard cash. “Our culture and heritage is what makes the UK great,” added UK Culture Secretary Sajid Javid. “By making them accessible to new audiences abroad it will also help drive more visitors to our shores.”

The proletarian Bard

Shakespeare, favorably viewed in earliest Communist days as an anti-capitalist, does not need much introduction to Chinese audiences. High school graduates are expected to know him and to have read at least excerpts of some of his plays.

A survey earlier this year found that Chinese see Shakespeare as one of the top five positive British icons, says Nicholas Marchand, arts director in China for the British Council, the government body that promotes British culture worldwide. “It’s not only the queen and Benedict Cumberbatch,” he adds.

Shakespeare first became known in China in 1903, when Charles and Mary Lamb’s childrens’ version of some of his plays was translated as “Strange Tales from Overseas.” Since then many translations have appeared; after the Communist revolution Shakespeare became part of the acceptable foreign canon.

That was because he was deemed by an official critic, Bian Zhilin, “to have opposed the feudal system in the early part of his career and exposed the evils of capitalism in the later part,” wrote Shakespeare scholar He Qixin.

That kind of political focus sometimes led Chinese critics to see things in Shakespeare’s plays that Western audiences might not. The love between the star cross’d lovers in Romeo and Juliet, for example, reflects “the desire of the bourgeois class to shake off the yoke of the feudal ethical code,” according to Lai Ganjian, a critic writing in 1979. Shakespeare has never fallen foul of Chinese censors.

The Bard without the bawdy

This could also have something to do with the fact that until now, Chinese translators have deliberately skipped the naughty bits.

“None of the earlier Chinese editions have taken the sexual allusions into consideration," says Prof. Gu Zhengkun, a translator and chief editor of the translated collected works currently being published in Beijing. “Translators have not rendered the bawdy words because they thought they would damage Shakespeare’s image as a moral writer.”

Though his works are studied, they are not often staged, says Joe Graves, an American theater director who has worked in China for more than 10 years. In that time, Mr. Graves has put on 18 professional productions of Shakespeare’s plays. “What is wonderful," he says, "is that very often it is the first time that people in the audience have seen the story,” so they are unusually caught up in the plots.

But a lot is missing, says Prof. Gu. “So many translations sound like modern writing, commonplace novels, or plays,” he complains.

Even when the translations are beautifully poetic – many scholars point to Zhu Shenghao’s classic versions, written in the 1930’s – they are not necessarily faithful to the original texts. “There are many inaccuracies in his work, and sometimes he misses the point,” says Cheng Zhaoxing, one of China’s top Shakespearean scholars.

Playful poetry isn't easy to translate

“We need new translations, but it is very difficult to offer something better,” Prof. Cheng says. “Good scholars are not always good translators or great poets in Chinese. Such combinations are quite rare.”

Shakespeare’s poetry is especially difficult to translate fully because of its often “playful” nature, says Perng Ching-hsi, a Taiwanese scholar who has just finished translating “King Lear.”

“Puns are particularly difficult to catch, but you can’t stop a performance to explain a pun to the audience,” Prof. Perng points out.

Such is the challenge facing the translators whom the Royal Shakespeare Company (RSC) hopes to recruit to come up with fresh and catchy translations that will speak to modern Chinese audiences.

The plan, says RSC spokeswoman Liz Thompson, “is to have the writers and translators and interpreters embedded in the rehearsal room with the director and actors, watching them working on the words” as they prepare English language productions in London and Stratford-upon-Avon.

That way, Ms. Thompson hopes, “they will make translations specifically for performance, looking at the text not as a piece of verse or prose but as something to be performed.”

The first fruit of this project should be a 2016 Chinese language production of “The Merchant of Venice” – the first Shakespeare play ever presented in China, in 1913 – on the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death. By 2023, the 400th anniversary of the publication of the First Folio, his first collected works, the RSC hopes to have translated all 38 of Shakespeare’s plays into Chinese.

“Shakespeare is now owned by all the world, not just by English speakers,” says Neil Constable, chief executive of Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre in London. “He is a significant international brand; it’s good that everyone feels they have a part of him.”