Hong Kong democracy march draws thousands, but can it create change?

Loading...

| Hong Kong

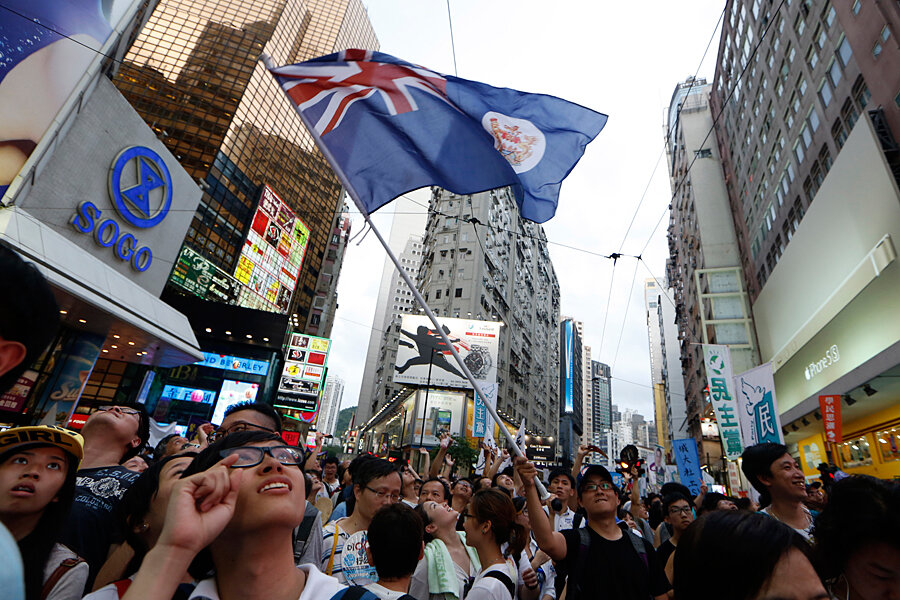

A seven-hour stream of demonstrators marched across Hong Kong Island today, seeking to send the message that they expected a greater say in their government. Yet, optimism gave way to uncertainty as the day wore on, and by midnight police descended on protester sit-ins threatening to clear the encampments.

Commemorating the 1997 handover of Hong Kong to China, July 1 is a public holiday here. Ever since 2003, when a half million people took to the streets in protest of an internal security bill, the day has served as an opportunity for disgruntled residents to air their grievances with Beijing. Organizers estimated a turnout of 510,000 people – which would make it the largest July 1 protest yet – while police put the number closer to 98,600 at the march's peak.

“The people of Hong Kong have spoken – we want genuine universal suffrage,” said Benny Tai, a Hong Kong University law professor speaking from a stage in Chater Garden, a park in the city’s Central district. Mr. Tai was one of three organizers of Occupy Central with Love and Peace (OCLP), a civil disobedience movement that organized a referendum on political reform that drew Beijing’s ire.

More than a year ago, in early 2013, Tai announced that OCLP would shut down Central, the city’s finance district, with 10,000 protesters on July 1, 2014 if the local government failed to deliver political reforms. Tai, OCLP, and many Hongkongers want to vote for their top leader, the chief executive, who is currently selected by a group of 1,200 political and business elites sensitive to Beijing’s wishes. Tai praised the day’s emphasis on nonviolent protest.

Rolling up his colonial-era Hong Kong flag around 11:00 pm, young protester Richie Ling says he felt compelled to participate in this year’s march because of “unjust actions” by his government. These include Hong Kong pushing forward plans to develop its northeast New Territories near mainland China, which many locals feel is an attempt to move the border southward. Mr. Ling says he was bothered by Beijing’s refusal to allow Hongkongers universal suffrage and the ability to nominate their own candidates in the 2017 chief executive election.

A disconnect?

Earlier in the day, the Hong Kong government celebrated the 17th anniversary of the return to Chinese rule. Chief Executive Leung Chun-ying presided over a ceremony including his two predecessors and mainland Chinese representatives as the Chinese and Hong Kong flags were raised over Victoria Harbour.

Shortly afterward, demonstrators marched below the former colonial flag of Hong Kong and the flag of the Republic of China, Chiang Kai-shek’s nationalist government that fled communist forces for Taiwan in 1949. These flew alongside more than two miles of signs and banners promoting causes including local democratic parties, farmers, and various rights organizations.

The disconnect between the staid government event and the massive turnout for the democracy march underlined the current political situation in Hong Kong. On one side, there are pro-Beijing officials and businessmen and the more conservative residents of the city. The other side is made up of democracy activists – primarily youth and the educated middle class – who are demanding a level of self-determination never allowed by the British, but promised by Beijing pre-handover.

At the end of the march, two student groups "occupied" two significant locations: a park in the central business district, and the space surrounding the chief executive’s office. They planned to leave the following morning, so as not to disturb traffic on the densely populated island. Preliminary reports say that police began moving in on the students around 2:00 am on July 2.

“Today was successful in that many people came for this so-called protest,” says Sadie Lau, who participated in the march.

Despite the high turnout, the day’s demonstration won’t necessarily achieve its goals, Ms. Lau says.

“It’s an ongoing fight against two governments.”