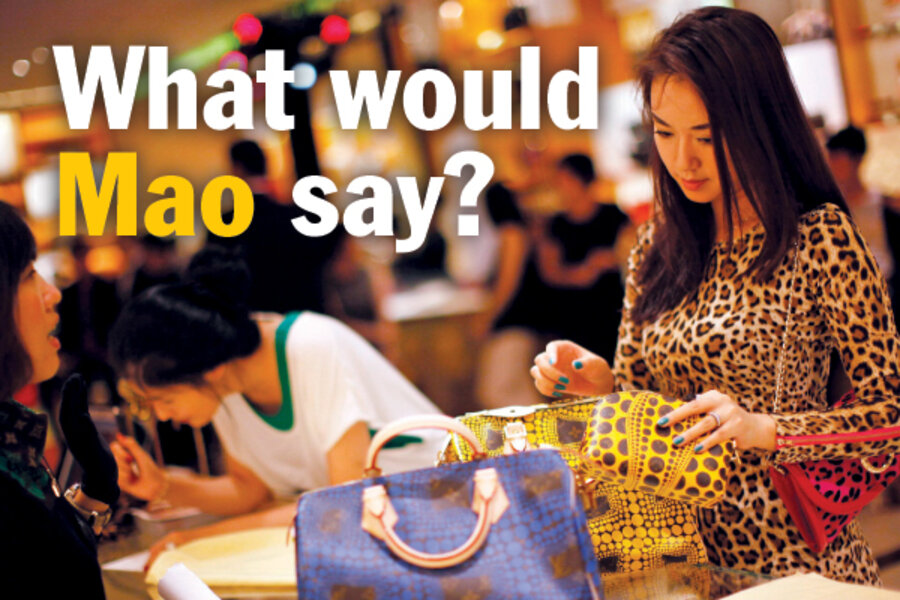

Chinese Communist Party: Would Mao recognize the paradox?

Loading...

| Yangjiaxiang, China

Yang Youwei owns a slaughterhouse, holds a big chunk of shares in a nearby coal mine, sits on the coal mine board, and runs the company that sells the mine's production. He drives a black Rolls-Royce.

He walks like a capitalist; he talks like a capitalist. He is easily the richest man in this small village 300 miles south of Beijing. And he is also Yangjiaxiang's top communist, secretary of the local party.

Welcome to the paradoxical world of today's Chinese Communist Party.

Another example: Zhao Tiehong, a lively-faced woman in her mid-50s and one of the party's 83 million members. She has been a party cadre for more than a quarter of a century, ever since she got a middle-management job with a state-owned railroad company. Salt of the Communist earth, you might think.

But she laughs sardonically when asked to explain her emotional attachment to the party. "I feel no such attachment, and I don't know anyone who does," she says bluntly. "In our society, the Communist Party rules. If you get in, you have more chances to further your career. That's it."

Looking for a true believer?

Try talking to Chen Xiankui, a keeper of the flame in his job teaching Marxism at Beijing's People's University. Pinning him down on what exactly he believes in, though, is not easy given his insistence that "there is no fixed mode of socialism."

When you come down to it, Professor Chen explains, "the party's fundamental task is to make ordinary people richer."

As China's largely rubber-stamp parliament prepares to meet in early March to install a new Communist-led government, the party that claims also to be the incarnation of the Chinese nation and state is in crisis.

Rocked – not for the first time – by corruption scandals, bereft of inspiration or ideology, irrelevant to increasing numbers of Chinese citizens, and united only by an overriding determination to maintain its grip on power, the party "is now entering the riskiest period" of its history, warns Wang Changjiang. And he should know: He is the head of the "Department of Party Building" at the Central Party School in Beijing, the party's intellectual inner sanctum.

Professor Wang thinks that the solution to the party's ills is more democracy (though not too much democracy; a multiparty system "is not necessary," he says).

That is problematic for a party that has brooked no challenge to its rule since the Chinese revolution in 1949 and which is now just a decade short of the record for Communist rule – the Soviet Communist Party had 74 years in power.

The Chinese Communist Party is a political party unlike any other, Wang reminds you. "We did not win power through democratic elections but through revolution. Our system is a dictatorship," he says bluntly. "And our biggest challenge is still how to make the transition from a revolutionary party to a ruling party."

The party is everything ...

In China, as it was in the Soviet Union, the party is the state. The two are inseparable, since the party has colonized every aspect and function of the state, and no other group or institution is allowed even a taste of state power.

"The party is like a nerve that runs from top to bottom of society across the nation," says Li Weidong, an independent political commentator. "It's everywhere and it can do anything."

In fact, the party is more important than the state. It is no accident that Xi Jinping was made head of the Communist Party three months before his appointment as president of the nation during the National People's Congress meeting that opens March 5. He will become president because he is head of the party.

It is the same all the way down China's administrative pyramid to the hundreds of thousands of villages where the administrative village leader and the local party boss are very often the same man. And where they are not, as Mr. Yang explains, "the party chief is senior to the village chief."

The Communist Party's domination of the state is rooted in its control of the military. Power, Mao Zedong used to say, grows from the barrel of a gun, and the People's Liberation Army is not the Chinese national army; it is the Communist Party's private army. Since the party sees itself as the incarnation of the nation, though, officials see no contradiction.

The party also controls all three branches of government: The overwhelming majority of delegates to the National People's Congress will be party members; the current 28-strong cabinet includes only two non-Communist ministers; and the judiciary, too, is under the party's thumb.

Courts are usually closed to outsiders, but it is no secret that in any case of interest to the party, judges must take their orders from an "adjudicating committee" made up mainly of party members, which decides questions of innocence and guilt.

These committees meet in secret, but party interference in court affairs has become so embarrassingly obvious that the new head of the party's Politics and Legal Affairs Committee, Meng Jianzhu, last month criticized "the passing of paper slips" to judges by local party bigwigs during court hearings, instructing them how to rule.

The party also guides economic planning, and it manages more than half of China's economic output through state-owned enterprises that still control key sectors such as oil, telecommunications, banking and insurance, mining, steel, aviation, airports, railways, highways, automobile manufacturing, and health care.

The party's Organization Department names the bosses of the big state-owned enterprises, and the presidents or vice presidents of the biggest firms almost always also head their company's Communist Party committees.

And, of course, the party's propaganda committees at the national and local levels determine what appears in newspapers and on TV, though they have a harder time censoring the Internet.

... yet the party means little to daily life

Despite keeping its hand on all these levers of power, the Communist Party is scarcely a dominant presence in most Chinese citizens' lives, says Bruce Dickson, a professor at The George Washington University in Washington, D.C., who has made a close study of the party.

In recent years, he says, the party has been stepping back from ordinary people's daily lives and is now "like background noise, not as prevalent as we often think. And as it becomes less relevant and necessary to people's lives, the risk is that the regime will become less stable," he adds.

Twenty years ago, the party was still oppressively omnipresent; its cadres told citizens which jobs they would take, where they would live, even when they could have a child. That is no longer remotely the case.

"The party has developed a more nuanced strategy on what it is concerned about and what it will let go," explains Professor Dickson. "It has adopted a more targeted type of oversight and repression focused on the individuals and the kind of information it wants to control. Otherwise it is content to let people run their lives without much interference."

"As soon as you do anything with any relevance to something the authorities say is political, they can get in your way," says Zhang Qianfan, a constitutional lawyer whose outspoken defense of the rule of law has often drawn the government's disapproving attention.

"But if you just care about your daily existence," as do the vast majority of Chinese citizens, he adds, "you don't feel the party's existence except at 7 o'clock in the evening" when the prime-time national TV news inevitably opens its broadcast with an interminable account of the party leaders' activities that day.

Shen Liyong, for example, an entrepreneur in his mid-30s who moved to Beijing to set up his own travel agency, reckons that "most people are like me. I don't care much about the party, and I just want to live my own life."

Mr. Shen happens to be a party member. As a class monitor in graduate school, he was picked by the dean, "and I thought 'why not?' It didn't matter one way or the other to me," he recalls. But when he graduated and left home, he didn't bother to tell his university party committee where he was going; and since then, he has not so much as paid his dues.

Shen says he has not needed or used his party connections to grow his young business, nor does he imagine ever doing so. If his company ever grew really big, he knows, someone from the party would get in touch with him and suggest that he allow the creation of a party cell. And if that happened, he says, "I would need to cooperate." But until then, he adds, "I prefer to run my business by myself and not get involved with officials."

The only real reason to join the party now, Shen says, is for someone to get ahead if they end up working for the government – either as a civil servant or as an executive in a state-owned enterprise. That seems to be a very widely held view, even among party members.

But in today's China, fewer and fewer people work in the state sector; a recent analysis of official Chinese figures by the Peterson Institute for International Economics in Washington found that only 10.2 percent of the workforce is employed by the state.

The closure or privatization of state-owned enterprises since the mid-1990s and the growth of a market economy mean that "people's dependence on the party has grown less and less," says one young party scholar who asked not to be named.

At the same time, while the party may maintain its grip on the commanding heights of the economy, it has lost control of the foothills. The young scholar's father, for example, is the party secretary of the company where he works. When it was a state-owned enterprise he was influential; since it was taken over by private owners, says the scholar, his "role has been reduced to a union leader, handing out goodies at New Year."

Party corruption is the 'No. 1 problem'

Party cadres can exert their power, in their roles as government officials, by providing or withholding the sort of cooperation a business needs to get permits and licenses and jump through other bureaucratic hoops. But such cooperation often comes at a price in a system where corruption is endemic.

"We used to see corruption as a problem of individual cadres," says Wang, the Party School expert. "But we have realized now it is systemic and can be solved only by limits on [party] power."

Mr. Xi, the new Communist Party leader, has launched a campaign against corruption, warning soon after he took over last November that popular disgust at rampant dishonesty among Communist officials could "ultimately lead the party and the nation to perish."

"Party corruption is the No. 1 problem in ordinary Chinese people's minds," says Lin Zhe, who wrote the party's first graft-busting textbook. "It is undermining the party's legitimacy, and we have to do something about it before people's patience snaps."

Most Chinese citizens see graft firsthand only in the local officials they come across. But the scale of corruption all the way up party ranks – to the very top – was open for all to see in the very public scandal – involving murder, sex, betrayal, and gross corruption – that brought Bo Xilai down last year. Mr. Bo, a former politician and once a contender for a place on the party's Standing Committee (its seven-man pinnacle), is due to go on trial soon on a range of charges including corruption.

But Bo is not the only man to have profited from his membership in the "red aristocracy," a group of several hundred families descended from revolutionary heroes and early leaders of New China after 1949. They have made themselves immensely rich, parlaying their political power into financial wealth through a system of crony capitalism that is widening the gap between rich and poor.

For a party that came to power on promises of equality, this is dangerous, Wang acknowledges. "The scandals threaten the party's authority," he says. "Even though the economy is growing, the party's credibility is declining."

Not that anybody in China has a clear idea of what the alternative to Communist Party rule might be.

Can anyone imagine China without the party?

"In most people's expectations, the country simply cannot live without the ruling party. They cannot imagine it," says Mr. Zhang, who recently published a daring open letter pleading with the government to put the national Constitution above party rules.

"That's the dilemma," he explains. "The party has created a political vacuum in society to make China totally dependent on it."

Shen may not feel any attachment to the party he joined as a student, and does his best not to have anything to do with it, but he is glad it's there. "At the moment I think having the party is better than not having it, because I don't want to see the country fall into chaos," he explains. "We are living in a stable time with economic growth. That makes us luckier than our ancestors."

The feeling that there is no alternative to the party's rule only deepens a sense of powerlessness among many citizens, if they bother to think about it at all.

"Ordinary people can't change anything in China, and they'll only hurt themselves if they try," says Mrs. Zhao, who is coming up to retirement from her job on the railways.

"Nowadays ordinary people can't do much about corruption," agrees Yang Xianshui, a retired coal miner in the village ruled by its capitalist-Communist leader, Yang Youwei. He is delighted by his village's prosperity but disappointed by the "negative trends" he sees spreading across the country.

"People are reluctant to talk about it, though," he says. "It's too risky."

The retired coal miner may not air his criticisms, but he knows what is going on. The Internet Age has brought information to Chinese citizens as never before, and there is little the Communist Party can do to suppress it, hard as its officials might try.

"For years Chinese people were like Peking ducks," says Zhang, the constitutional lawyer. "They could eat only what they were fed. But now people know more facts."

That knowledge and growing material prosperity have "awakened people's awareness and sense of their rights, and weakened their tolerance of privilege and corruption," the official mouthpiece of the Communist Party, the People's Daily stated last month in its overseas edition.

The paper was commenting on a recent recommendation by Wang Qishan, a new member of the party's top body, the Standing Committee, and the man in charge of the anticorruption drive. Mr. Wang had advised his colleagues to read a book by historian and philosopher Alexis de Tocqueville called "The Old Regime and the French Revolution" as a cautionary tale.

The book explains how the French monarchy was brought down by the nobility's indifference to social inequality and insistence on protecting their privileges.

"Contemporary China ... shares certain similarities with pre-Revolutionary France," the People's Daily article warned, citing a widening gap between rich and poor, "social injustice," and "class solidification" as dangerous parallels.

It was a striking admission by the organ of the party that seized power pledging to "serve the people" and which has ruled in their name for more than six decades.

"It would be dangerous," Wang worries, "if the party's authority and strength continued to decline. I hope reform can halt that decline. But reform must break the links between political power and economic interests. The important question now is whether sufficient sense of responsibility and courage exists to do that."