The real reason China-Japan are locked in a territory dispute

Loading...

| Taipei, Taiwan

As China and Japan spar over control of a group of tiny islets in the sea between them, the deeper issue is really the question of which of Asia’s two biggest economies will gain control first of the valuable oil and natural gas located there.

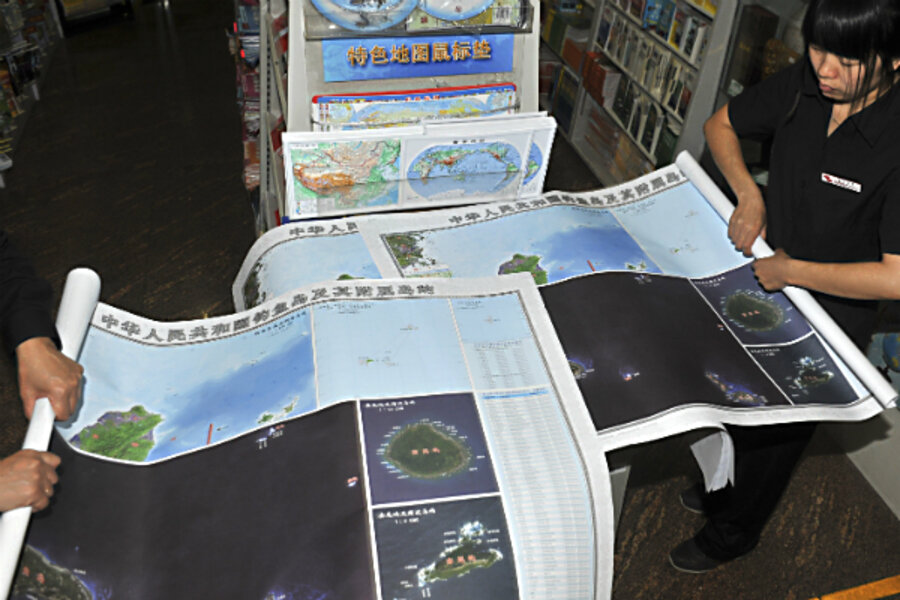

Since mid-September, a number of Chinese ships have sailed close to the eight uninhabited islands in the East China Sea in order to assert Beijing’s claim there. Japan now controls the islets, known as the Senkaku in Tokyo and the Diaoyu in Beijing. Japan’s announcement in September that it was buying the Senkaku, sparked mass street protests in China and a diplomatic crossfire so intense that US officials have urged calm.

“If they could get it, oil and gas would be hugely important,” says Liu Chia-jen, petrochemicals analyst with KGI Securities in Taipei. “But whoever makes that move will run into trouble,” he says, adding that because of those tensions, the potentially enormous oil and gas fields in the region are likely to stay untapped for a while.

China is the second largest net importer of oil after the United States. Heavily-industrialized Japan is the third.

Years of rapid growth has sent China's fuel consumption soaring, and the country has been quicker than Japan in plumbing the East China Sea. Japan, which has relied heavily on nuclear power, has also seen its oil usage jump since its nuclear power plants went idle after the Fukushima nuclear power plant crisis last year.

How much is under the sea?

Just how much oil is at stake in the East China Sea is uncertain.

CNOOC Ltd., a Chinese offshore driller, listed its East China Sea proven oil reserves at 18 million barrels and gas reserves at 300 billion cubic feet last year.

The US Energy Information Administration, meanwhile, estimates that the East China Sea has between 60 and 100 million barrels of oil in “proven and probable reserves” and 1 trillion to 2 trillion cubic feet in natural gas reserves.

“No one really knows how much is there because the disputes have discouraged exploration,” says John Pike, director of the US-based public policy organization GlobalSecurity.org.

And because of the tensions in the region, only 2 to 3 percent of the world’s total oil discoveries have come from the 482,000-square-mile East China Sea spanning from Taiwan to Japan to date, Mr. Liu says.

The Senkaku dispute highlights an unsettled history between Japan and China. China claims that Japan has not adequately apologized for World War II-era aggression, though Japan says it has atoned, for example.

Requests for resources from Japan are stalled because of a “lack of a satisfactory settlement of the historic legacy, that is to say lack of an apology from Japan,” says Joseph Cheng, political science professor at City University of Hong Kong.

China and Japan have been successful at working together to tap large oil fields in the region in the past: China discovered the Pinghu oil and gas field in 1983, and its production there peaked at between 8,000 and 10,000 barrels per day in the late 1990s, according to the US government’s Energy Information Administration. Japan co-financed two pipelines from the Pinghu field to China through a regional development bank and a Japanese lender for international cooperation.

Today’s competitors also signed a deal in 2008 on sharing resources from an East China Sea gas field called Chunxiao by Beijing and Shirakaba by Tokyo. But they couldn’t figure out how to work together on it, and two years later Japan accused China, which had drilled in the field since 2003, of going ahead on its own.

China and Japan could use another agreement, suggests Scott Harold, associate political scientist with the American think tank RAND Corp.

“Until the two sides can reach a deal on exploration or extraction, it’s unlikely anyone will be pulling much of value out of the seabed,” Mr. Harold says. Otherwise, he says, “one missile or one well-armed ship could take out an adversary’s rig.”