Why China is likely to get more involved in Afghanistan

Loading...

| Beijing

As the United States and other Western nations prepare to withdraw their military forces from Afghanistan, China is growing nervous about the prospect of chaos after they have left.

So, after years of standing in the background, Beijing is starting to show signs of closer engagement with its strife-torn neighbor in a bid to ward off disaster, say Chinese and foreign analysts.

When Afghan President Hamid Karzai meets his Chinese counterpart Hu Jintao here on Friday, they will raise their countries’ bilateral relations to a “new strategic level,” an Afghan official told reporters in Kabul this week.

Though it is still unclear what that will mean in practice, the step reflects Beijing’s feeling that “it is urgent that China strengthen its relationship with Afghanistan,” says Zhang Li, an expert on South Asia at Sichuan University in Chengdu.

“Afghanistan’s security situation will have a direct impact on China’s security,” he adds. The Western military pullout “clearly presents China with more problems than opportunities.”

China to the plate

Some observers here believe it is time that China stepped up to the plate. “It is not rational to rely on a distant and remote country to provide security for the region,” says Hu Shisheng, an analyst at the China Institute for Contemporary International Relations, referring to the United States. “China has to take more responsibility.”

But after leaving things to the Americans for so long, warn others here, Beijing may not be well placed to exert influence. “We cannot play a significant role because we do not have a sufficient presence in Afghanistan,” cautions Ye Hailin, an Asian affairs analyst at the China Academy of Social Sciences, a government-linked think tank in Beijing.

The one thing China will not be doing as Western soldiers leave Afghanistan is get involved militarily there itself. With scarcely any experience of peacekeeping operations abroad, the Chinese Army “would be stepping into uncharted territory in a potentially very kinetic situation,” points out Raffaello Pantucci, a scholar who follows China’s relationship with Central Asian nations. “It would be a huge jump for them.”

“We are not qualified to play a military game in Afghanistan,” adds Mr. Ye. “Only empires can do that, and neither the British, nor the Soviet Union, nor the Americans have won.”

The security question

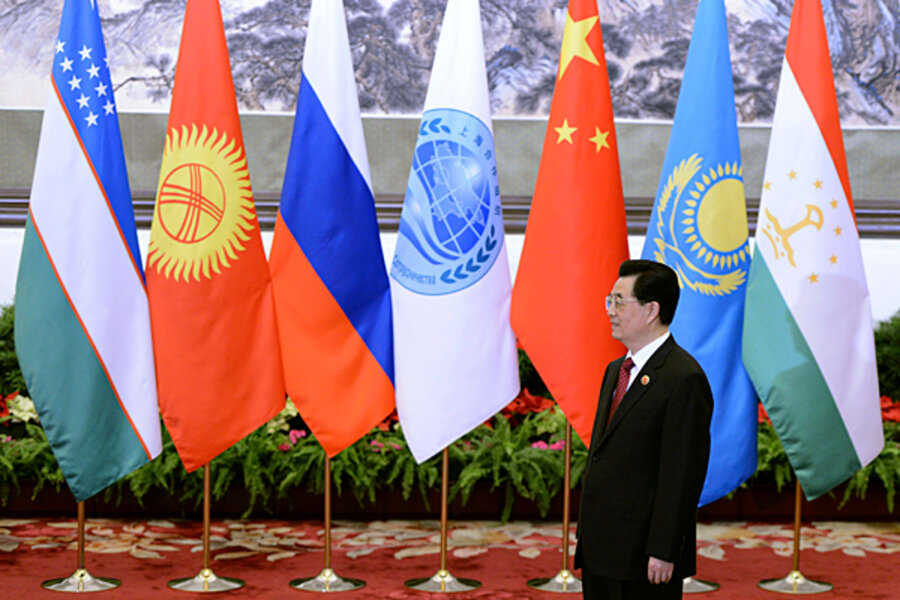

Closer ties with Kabul could bring more aid, more infrastructure projects, and more training for Afghan policemen and soldiers, say Chinese observers. That security support, they suggest, could come through the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, a group of Asian nations led by Beijing and Moscow at whose summit here this week Afghanistan is expected to be admitted as an observer.

Beijing is also likely to step up its tentative diplomatic involvement in the Afghan conflict, suggests Professor Zhang, after it hosted a first trilateral meeting with Afghan and Pakistani officials last February that “showed China’s intention of strengthening its influence in Afghan security issues.”

At that meeting, Chinese diplomats reportedly sought to convince the Afghan and Pakistani governments to work more closely together to regain control over their borderlands. Armed Uighur separatists, fighting for the independence of China’s mainly Muslim Xinjiang region, which abuts Afghanistan and Pakistan, are believed to have set up camps in North Waziristan. (See map here.)

“Stability in those tribal regions is of utmost national security importance to China,” says Mr. Hu.

Why China cares

If Western troops leave the Afghan Army and the Taliban still locked in combat, China is worried that the Uighur “East Turkmenistan Independence Movement,” which Beijing regards as a terrorist group, might find refuge in Taliban-controlled zones. Officials here also fear an upsurge of drug smuggling through Xinjiang.

More frightening, though, is the prospect that continued fighting and possible Taliban gains would spill over into Pakistan, China’s closest regional ally. “A disaster in Afghanistan could undermine China’s strategic bulwark in the region,” points out Andrew Small, an analyst at the German Marshall Fund in Washington who is writing a book about China’s relationship with Pakistan.

At the same time, a security vacuum in Afghanistan could prompt a proxy conflict there between regional rivals India and Pakistan, further complicating China’s position.

“If Afghan troubles spilled into Pakistan, that could turn our alliance into chaos,” warns Ye. “China has the same interest as the Americans in preventing Pakistan from becoming a nest of terrorists.”

Indeed China’s interests in Afghanistan coincide strongly with Western interests, says Mr. Pantucci. “They want a stable, peaceful, prosperous country that they can trade with and build roads through and where they can seek natural resources,” he says. “Stability in Afghanistan would contribute to stability in Central Asia, and that would help Beijing develop Xinjiang, its biggest and poorest province.”

For the past decade, China has not played a significant role in Afghanistan. Its state owned companies have built roads and invested $3.5 billion in a copper mine, but according to the Chinese Embassy in Kabul, Beijing has contributed only $246 million in aid over the past decade; that is less than one-tenth of Japan’s aid, or half of South Korea’s.

Until now, concerns in Beijing about the proximity of NATO bases to Chinese territory have been offset by relief that at least somebody else was dealing with the problem in Afghanistan.

Now, says Zhang, “China has to face the fact that a withdrawal timetable has been confirmed and we have to focus on all the new problems that may crop up.”

In the US, adds Ye, “a lot of people may think that after their military withdraws in 2014, Afghanistan is not their business anymore. We, on the other hand, see 2014 as a very crucial year for Afghanistan, but we don’t see it as the end of anything. We are going to have to live with that.”