From unlikely undercover agent to East Timor's first lady

Loading...

| Dili, East Timor

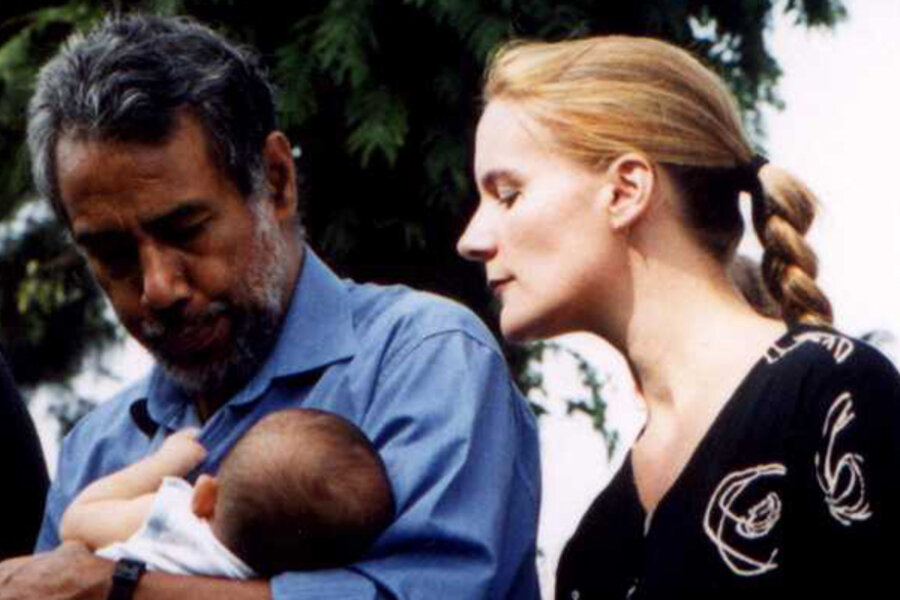

Young, blonde, and Australian, she was an unlikely undercover agent for an unlikely cause: a far-flung province on a Southeast Asian island that had been in a bloody fight for independence for more than two decades.

Most of her colleagues were either guerrilla soldiers fighting Indonesian troops in the jungle-thicketed hills of their native East Timor, or resistance leaders serving life sentences in prison in Jakarta.

From her apartment in the Indonesian capital, however, Kirsty Sword Gusmao – who worked as a human rights activist by day and as Ruby Blade, her nom-de-guerre, by night – was a key element in the eventual success of the underground Timorese movement that become the cause-célèbre among Western outsiders in the mid-1990s on the heels of a bloody massacre.

Working as a courier shuttling correspondence between guerrillas, Ms. Sword Gusmao also facilitated asylum applications, lobbied for international media coverage, and acted as personal secretary to the leader of the resistance, Jose Alexandre “Xanana” Gusmao, who was serving a life term in Cipinang prison in Jakarta.

“Most evenings, I would have Timorese knocking on my door," Sword Gusmao explains from the home she shares with her now-husband Xanana and their three boys in Dili, East Timor's dusty, village-like capital of roughly 250,000 that overlooks a turquoise bay framed by palm-fringed hills.

"They were either in trouble or the military was coming after them, or they needed help getting out of the country, or a human rights report that needed translating and safely e-mailed out of the country.”

Her relationship with Xanana began as furtively as her work in the resistance. Smuggling in English grammar lessons and document translations to his Jakarta prison cell, Sword Gusmao also managed to smuggle in video cameras, laptops, and cellphones – materials that greatly helped Xanana’s capacity to undermine Indonesia’s hold over East Timor.

Xanana was released from prison in 1999 and, after serving as the country's first president in 2002, was elected prime minister in 2007.

“Kirsty has greatly understood my personal limitations and obligations, and without her, my life would have been very difficult,” says Xanana today from his office in the colonnaded Government Palace.

The new struggle

It has been 10 years since East Timor finally declared independence from Indonesia after a UN-brokered peace deal three years earlier. Sword Gusmao has transitioned from helping the nation fight for independence to fighting for women’s rights – keeping with her the resistance movement’s motto “a luta continua” (the struggle goes on).

Through the Alola Foundation, a women’s empowerment organization that she founded in 2001, Sword Gusmao has lobbied for greater gender equality by establishing literacy, advocacy, economic development, and maternal and children’s health programs. One of the foundation’s greatest successes, she says, has been helping to secure a 2010 law criminalizing domestic violence.

While considerable improvements have been made since independence, the challenges still facing this nation of 1.1 million are vast. Only 2 in 5 homes have electricity, more than 40 percent of the country lives on less than $1 a day, youth unemployment is a staggeringly high 70 percent, and domestic violence is rampant, affecting nearly one-third of women older than 15, according to government statistics. More than 1 in 2 women suffer from domestic abuse in the capital alone.

“The law is a great step forward and awareness among the public has greatly improved that domestic violence is a crime – and a barrier to development, and to women’s health and well-being,” Sword Gusmao says. “But we still have a long way to go in terms of providing our law-enforcement agencies with the tools to be able deal with it adequately, and we need more and better women’s shelters, and legal and other services for women who have survived domestic violence.”

Come a long way

Activists point to a long and brutal history of colonization as one reason for the violence and trauma that still scar Timorese society.

After nearly 500 years of Portuguese rule, East Timor became an independent state in 1975, only to be bloodily annexed one week later by Indonesia. During the 24-year takeover, one-third of the Timorese population died from famine, violence, and disease.

Uprisings were routinely stamped out, demonstrators forcibly disappeared and the tortured, headless bodies of activists dumped around villages served as macabre threats to those hoping to for an end to foreign rule.

The mass shooting of at least 250 pro-democracy demonstrators in the capital in 1991 thrust the country into world view and helped its fight for self-rule become an international cause.

When East Timor finally voted for independence in a 1999 referendum, Indonesian troops ransacked the country, destroying essential documents, burning down private homes and public buildings, and sending thousands of Timorese into the relative safety of the hills. “The country was smoldering. The population was traumatized,” Sword Gusmao sighs. “Rebuilding from scratch has been no easy task.”

New documentary on Sword Gusmao

“Behind her gentle façade, she has a steely determination,” says British documentary filmmaker Peter Gordon, who hired Sword Gusmao in East Timor as a researcher for a 1991 Yorkshire Television documentary on the country. He says that at the time, “everywhere we filmed, [Sword Gusmao] seemed to embrace and be embraced by all those she had contact with.”

Despite being the subject of two new films – Peter Gordon’s second documentary on East Timor, "Bloodshot: The Dreams and Nightmares of East Timor," and the feature documentary "Alias Ruby Blade" – Sword Gusmao plays down her contribution.

“A lot of people think what I did was terribly dangerous and terribly intriguing, but really it’s what you do when you’re a human rights activist, you’ve got a conscience and you’re able to do something.”

Not all her work has been free of controversy: She’s recently come under fire for spearheading a pilot education program for children during an election year for her husband.

Sword Gusmao is hopeful for the future, pointing to legislation requiring one-third of all seats in parliament to be reserved for women, improvements in maternal and children’s health, and great reductions in infant mortality rates.

“Expectations have been huge, not just among ordinary citizens but policymakers and leaders of the country as well – everyone has been impatient for change to come,” she says. “But I think what we have managed to achieve is commendable and a cause for celebration.”