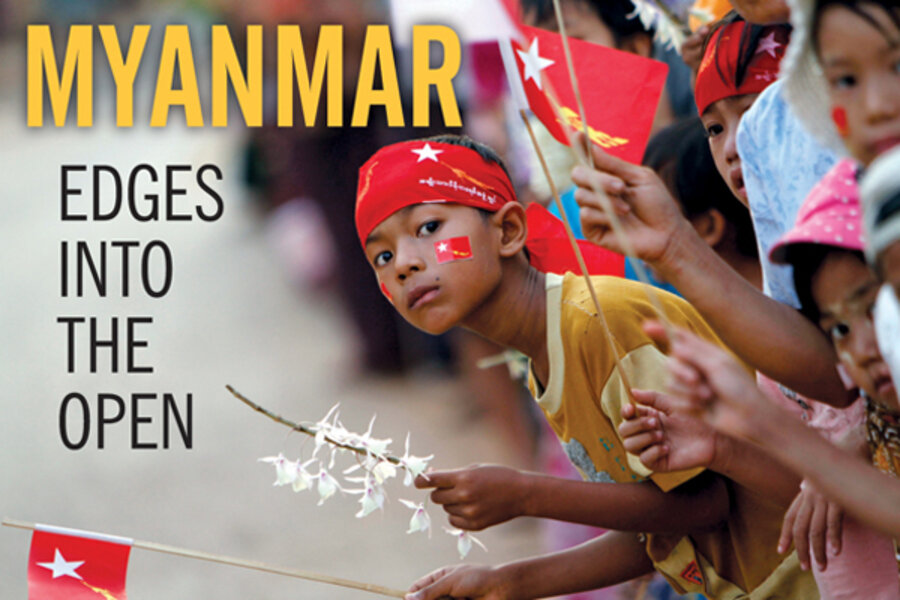

Is Myanmar about to rejoin the world?

Loading...

| Yangon, Myanmar

Soon after dawn one recent morning, before the full force of Myanmar's oppressive heat had gathered, a slim young woman in a white blouse and a long green wrap-around skirt stood outside a factory gate on a tree-lined, potholed avenue on the outskirts of Yangon and surveyed the crowd of several hundred women like her squatting or sitting in the dust at her feet.

Moe Wai was doing something that had been unthinkable since the military seized power in a coup a half century ago in what was then called Burma (the military government changed the name of the country to Myanmar in 1989); she was organizing an independent trade union.

She spoke simply to the women and girls who listened silently, all workers at Tai Yi, a Taiwanese-owned footwear manufacturer where they earn about $3.50 a day, including overtime. "An organization would be more effective than individuals when it comes to making our demands," she explained.

Little more than a year ago, that kind of talk might have earned Ms. Moe Wai a long jail sentence. Today, however, the right to organize a union is enshrined in a new labor law, one of a slew of liberalizing reforms that Myanmar's nominally civilian government has enacted or planned since it took office in March 2011.

The new government, dominated by President Thein Sein and other former generals, has freed several hundred political prisoners (though many are still behind bars), relaxed censorship (though not abolished it), and held parliamentary by-elections earlier this month that pro-democracy icon Aung San Suu Kyi swept in a landslide victory.

Where these changes are leading, and how lasting they will be, nobody is quite sure. Many, like Dhin Dhin Mar who cuts leather at Tai Yi, are reserving judgment. "We'll see how much use this union is when we hear what's happened to our wages," she says.

But there is a palpable mood of hope in Yangon as people allow themselves to dream that their country may at last be on a path out of the fearful, downtrodden poverty to which decades of harsh and incompetent military rule have condemned it.

"The fear factor is gone," says Thiha Saw, a crusading newspaper editor. "People are getting bolder and bolder. We call ourselves 'Brave New Burma.' "

This is no Arab Spring

Do not mistake Myanmar's emergence from its repressive cocoon for an Asian variant of the Arab Spring. The citizenry may have yearned for greater freedom, but the Army had little difficulty in suppressing two outbursts of popular anger – a student uprising in 1988 and the so-called Saffron Revolution led by Buddhist monks in 2007.

Today's transition to democracy – if that is what it turns out to be – is happening on the military's own carefully planned terms, following a blueprint drawn up 10 years ago.

"The [civilian] government itself is an outcome of goodwill of Tatmadaw," the official daily New Light of Myanmar recently reminded its readers, using the Burmese word for the Army.

Just why the military decided to withdraw from the day-to-day running of the country is a question that has scholars and observers scratching their heads. Perhaps the generals realized how far behind its neighbors Myanmar had fallen economically; maybe they feared the country's heavy dependence on China; possibly they concluded they could lead their nation no further up a political and economic dead-end street. In any event, they wanted broader international acceptance and an end to US and other Western economic sanctions; only a move toward democracy would unlock that door.

Some regime opponents remain skeptical. "I know these people," says former Air Force Capt. Zaw Nyunt, who joined the 1988 uprising and then spent six years in exile in Thailand. "This is a period of soft political winds, but it won't last long. When they've got the right engagement with the West ... the winds will change."

Most of those hoping for change, though, are focusing more on what use they can make of the new political space that has opened up, now that the generals appear to have decided that "politics" is not a threat to Myanmar's security.

Most dramatically they voted overwhelmingly for the opposition National League for Democracy (NLD) in the April 1 elections, giving the party 43 of the 45 parliamentary seats at stake and propelling Ms. Aung San Suu Kyi from house arrest, where she had spent 15 of the past 20 years, to a leading national role.

"This is a free country. We have a right to vote," said Win Win Aye, a housewife explaining why she had gone to the polls. "Aung San Suu Kyi is like a mother to us."

The by-election results will not change the formal balance of power in parliament, where the military's proxy Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP) holds the lion's share of the 664 seats. The NLD will not have the votes to amend the Constitution, which the military wrote in 2008 to ensure its continued power: Chapter 1 guarantees the Army's "national political leadership role" and 25 percent of the members of parliament are military officers, a large enough bloc to prevent the majority needed for major constitutional change.

"Essential power will remain with the military, and they will play a central role for the foreseeable future," says David Steinberg, a professor at Georgetown University in Washington, D.C., and doyen of American Myanmar scholars. "I don't think Aung San Suu Kyi will be able to change that."

But the government will no longer be able to treat her as a "nonperson," nor does it want to ignore her any longer; it needs her to play an active role because Western governments will listen primarily to her advice as they consider lifting sanctions.

Aung San Suu Kyi needs the military, too, given its central role in modern Burmese history and its reluctance to return completely to the barracks. "It is particularly important that the military should be behind our reform process," she said just before the elections. "We hope to win the military over to understand that we have to work together."

Curiously, given her bitter experience at the hands of the previous military junta, she may be just the person to rally her former jailers.

Saintly reputation with authoritarian streak

Aung San Suu Kyi is an accidental politician, though she has honed her skills – and her meditation technique – even during long periods of house arrest in her family home, set amid spreading lawns on a small lake in central Yangon.

In 1988 she was living in England, but had traveled to Burma to visit her sick mother. When a student uprising broke out, she became a figurehead, and soon a leader, because of her ancestry: She is the daughter of Gen. Aung San, founding father of the Burmese Army and the nation, who was assassinated before Burma won independence in 1948. He is a national hero, after whom avenues are named.

Aung San Suu Kyi draws strongly on this legacy for her extraordinary popular support across the nation. And on the foundation of this positive name recognition she has built her own reputation from a powerful mixture of charm, charisma, and moral fortitude in resisting dictatorship and refusing exile, even as her British husband lay dying in Oxford in 1999.

"Gen. Aung San had two heirs: his daughter and the Burmese military," says a European diplomat who asked not to be identified by name. "Aung San Suu Kyi wants to unite them and embody their union; she does not present herself as an enemy of the Army as an institution, just of the way they have behaved."

Indeed, the almost saintly reputation she enjoys masks an occasionally authoritarian streak, say some who know her. "When important decisions have to be made quickly, she must act like a captain on the battlefield," says Myo Nan Naung Thein, a sometime aide to the NLD leader. "But discussion and debate are impossible – almost nobody else [in the party leadership] ever says no to her."

The NLD certainly has organizing power, but there is no doubt that the party owes its popularity almost entirely to its leader. It has no political platform beyond vague calls for national reconciliation and the rule of law, and little leadership depth. Though Aung San Suu Kyi is gathering a younger generation of advisers, veterans still fill key party positions.

"I met the 'uncles' recently," Professor Steinberg recalls of a discussion with the NLD top brass. "I was probably the youngest man in the room, and I'm 83."

"If the NLD was a soccer team, it would be one without a midfield and without fullbacks," says Khin Zaw Win, a former political prisoner who now works as a community activist. "They just have one lone striker."

That suggests that even should the NLD score the kind of victory at general elections due in 2015 that it won on April 1, some sort of ruling coalition with the military and the USDP might be the only viable outcome.

"All we've done in the opposition is sit in prison," laments Mr. Myo Nan Naung Thein. "We've read books, but we have been far away from power. If power was handed instantly to the NLD it would be a disaster."

In a country where individual leaders have always been more important than institutions, it is perhaps inevitable that the political process now under way should be based on a personal accommodation between two leaders – Aung San Suu Kyi and President Thein Sein, who persuaded her at their meeting last August to run for election.

But "that is very fragile," warns Steinberg. "Things have to move beyond these two people."

Aung San Suu Kyi may be the face of the opposition, indeed the face of Myanmar, to the outside world. "But hers is not the only voice," says Hla Hla Win, a researcher with Egress, a leading educational nongovernmental organization in Yangon. "Civil society leaders are taking new roles, and helping get people's voices heard."

Many other political voices

The voices that Moe Naing wants the world to hear are not obviously political; they are the voices of the a cappella choir he has formed at the Gitameit Music Center. The school is Myanmar's first such venture, housed in a rambling old hardwood-floored home in northwestern Yangon now ringing with the joyous cacophony of students practicing piano, guitar, and cello, and singing in small, poorly soundproofed rooms.

But there is a subtle political component to what Mr. Moe Naing is doing when he directs the choir, which all students must join. And that's what makes his music school more than just a place to learn music, turning it into another small brick in the growing edifice of Myanmar's growing civil society.

"There's a lot of meaning in music," says the former keyboards session musician, sitting in his office in front of a wall-to-wall gilded bas-relief representing Buddha. "Singing choir is working together. We can improve our unity and develop our sharing of ideas. There is a lot more result than just music, and it is thrilling to see this development."

All over Myanmar, but especially in the cities, young people are hard at work trying to rebuild social networks and give those networks purpose in a country where 50 years of dictatorship means they are starting from scratch: The military trashed the education system, banned independent unions and professional organizations, reined in charity groups, and ruled a fractured society with an iron fist.

For example, in a classroom at the British Council (the British government's cultural arm), the English Conversation Club that meets each Sunday afternoon is an exercise in consciousness raising as much as a lesson in vocabulary and grammar.

On a recent Sunday, volunteer teacher Khin Soe Min led a discussion of a simple fictional story the group had read about a tree in danger of being cut down to make way for a mall, threatening the birds, insects, and squirrels that had made their homes in its branches.

Demonstrations, letters to the mayor, and an appeal to the courts blocked the building of the mall and saved the tree. "If you stay silent, nothing happens. If you want something, you have to do something," Mr. Khin Soe Min said. But that was only part of the message he had hoped to get across. The value of trees, and the importance of the natural environment, was another key element, he explained. "I don't just want people to protest. I want them to understand why they are demonstrating, because they have knowledge."

Knowledge is in desperately short supply in Myanmar, where schools are poorly staffed, universities have been repeatedly closed to choke off student unrest, many educated Burmese have gone into exile, and international isolation has starved students of learning material.

But since cyclone Nargis killed 130,000 people and ravaged the Irrawaddy Delta in 2008, prompting a wave of volunteers to help with relief efforts, a plethora of nongovernmental organizations has sprung up to provide the sort of welfare and social services the government should provide but does not. Gradually, some of them have expanded their activities into the political realm of civic education.

Khin Zaw Win, for example, regularly leads groups of young trainers into the countryside where they typically base themselves at a Buddhist monastery and hold week-long courses for village leaders on leadership, management, social development, and any other issues they ask about.

"The questions are interesting," says Mr. Khin Zaw Win. "What is parliament? What is a member of parliament meant to do? What can we do about relations with China and the impact of their hydro projects on the environment? No question is too simple, and it's a pleasure to answer them. People are so hungry for this kind of thing."

"After decades of quiescence, we've found our people are quick to wake up ... and understand they have a part to play in the destiny of our country," says Aung San Suu Kyi.

Shaking citizens awake

Among those shaking his countrymen awake is Poe Phyu, a young lawyer who has made a name for himself helping peasant farmers defend their land rights – and has been sent to jail twice for his pains. He consults in a small, bare-walled, concrete-floored apartment furnished with just two desks and a few plastic chairs, overlooking a noisy alley in central Yangon. A few weather-beaten farmers wait patiently as he expounds (loudly – he is partly deaf as a result of prison beatings) on his new interest, labor unions.

Mr. Poe Phyu is helping the women at Tai Yi set up their union, but he admits that he is learning as he goes. "Burmese labor lawyers like me suffer from idea bankruptcy," he complains. "Most of us in this field have not learned international labor standards." So he is teaching himself: On the floor by his desk are piles of documents he found on the Internet – the Constitution of the "Labour Protect" trade union in South Africa, a piece of European Union legislation on works councils, guidelines from the Association of Southeast Asian Nations on good industrial relations practice.

Basic grass-roots efforts like this are having an impact, both on people's awareness and on government and business behavior. "NGOs have influence," says Kyaw Thu, who heads a coalition of local and international activist groups.

NGO lobbying persuaded parliament to amend a land law last year, he points out; a media campaign by environmental groups forced the government to suspend construction of a coal-fired power plant near the planned port of Dawei last January; and a women's group working with the Rakhine ethnic minority obliged Indian investors to do environmental and social impact assessments before going ahead with a development project that threatens to displace local families.

But the pressure groups' crowning victory, a triumph whose implications reverberated far beyond Myanmar's borders, came last September, when the government suspended work on the Myitsone Dam.

The shadow of China changes shape

Myitsone lies at the confluence of two rivers that join to form the Irrawaddy, Myanmar's sacred watercourse. It also lies at the confluence of two key challenges for the Myanmar government – its relations with neighboring China and its relations with ethnic minorities.

Ever since the previous military junta signed a $3.6 billion deal with a Chinese state-owned company to build a giant dam and hydropower station at Myitsone, in the northern state of Kachin, the project has been controversial.

Environmentalists feared ecological damage; the Kachin Independence Organization, which has been at war with the government on and off for decades, was angered by the desecration of its homeland; many people in Myanmar resented the fact that 90 percent of the project's electricity would be fed to China, while they themselves suffer persistent power cuts.

The dam, however, was a centerpiece of Sino-Burmese cooperation and an emblem of China's leading role in Myanmar's economic development. So when the new government bowed to a public campaign last September and announced the suspension of work on the project, it was a clarion call to the world that Myanmar's relationship with China was changing, and that the country was ready to reorient itself.

For 15 years, Myanmar has been an international pariah, subject to economic sanctions by the United States and other Western governments as punishment for human rights violations against political opponents and ethnic rebels. Starved of capital, technology, and markets, the ruling generals turned to China for diplomatic and economic support.

Chinese businessmen have poured into the north of the country, selling Chinese-made goods, establishing rubber plantations, and buying up timber, gems, and jade. Beijing sold the weapons to the junta, and its state-owned enterprises launched giant construction projects, such as a pipeline designed to carry oil and gas from a port on Myanmar's Indian Ocean coast to central China.

That pipeline, giving China its first direct access to the Indian Ocean, will be of extreme geopolitical significance to Beijing. Myanmar's generals, many of whom cut their teeth fighting Chinese-backed Communist rebels 40 years ago, appear to have seen potential danger in becoming so important to China, while needing its giant neighbor so badly.

The danger might be diffused if Myanmar had better relations with the West, and comments by senior US and European officials in the wake of the recent elections suggest they are prepared to start lifting sanctions, if only gradually.

Officially, Beijing has welcomed such a prospect. On the ground, though, Chinese influence seems bound to wane, say Chinese analysts.

"If Burma is to build relations with the West, it will have to make gestures that sacrifice Chinese interests," argues Du Jifeng, a Myanmar expert at the China Academy for Social Sciences in Beijing. "Chinese political and economic interests will definitely suffer, and Burma will not have to rely so much on China anymore."

That, of course, suits US policymakers, as they implement President Obama's "pivot to Asia," a shift of US geostrategic emphasis toward China's neighbors – such as Vietnam, the Philippines, and Myanmar – who are nervous about the Asian giant's burgeoning influence in the region.

Though the suspension of the Myitsone Dam project appears to have been mainly a gesture to the outside world, it also gratified the Kachin, one of the myriad ethnic minority groups that together make up more than 30 percent of the population and which have long resented domination by the majority Burmese ethnic group.

The Union of Myanmar, as the country is formally known, is a union in name only. The government has been fighting civil wars – using often savage tactics – with one or other of the ethnic minority armies in Myanmar's mountainous periphery ever since the country was founded in 1948.

Currently, only the Kachin are engaged in open hostilities. But more than 50,000 men and women remain under arms, and cease-fires with other ethnic groups such as the Shan, the Karen, and the Mon – leaving the rebels in administrative control of large areas – have only frozen the conflicts without resolving the minorities' grievances or granting their demands for political, economic, and cultural autonomy.

"The biggest challenge facing the country since independence is the relationship between the majority and minority populations," says Steinberg, of Georgetown University. "The real question is not democracy but a fair distribution of power and resources, and this is very, very difficult because there is exceedingly little trust on either side."

There are few signs yet of any willingness to compromise. The military has made national unity one of its cardinal values and sees federalism as the first step toward disintegration of the state. Aung San Suu Kyi campaigned recently on a platform of national reconciliation and wore ethnic dress when she visited minority areas, but she has never set out her vision of how she would seek to end more than six decades of civil war.

"The key to stability and democracy here is an answer to the ethnic issue," says the European diplomat. "That is the central problem facing the country, and there is still a big question mark hanging over it."

A whiff of profit attracts investors

Nor is the economic future entirely clear either, as the government and its team of foreign-trained advisers scramble to drag the country into the 21st century.

Myanmar has fallen decades behind its neighbors. Here, computers have not entirely replaced ancient ledgers, the infrastructure largely dates from the British colonial era, and once grand public buildings lie in disrepair.

Fifty years ago, Burma was a prosperous nation, the largest rice exporter in the world; but half a century of mismanagement under military rule ground it down until it became the second-poorest country in Asia, after Afghanistan, and the third-most-corrupt country in the world, according to Transparency International's rankings, above only North Korea and Somalia.

Myanmar is rich in natural resources, though. It has oil and gas reserves, huge stands of tropical timber, gems, jade, and precious metals. It also has a population of 60 million people, making it the second-largest market in Southeast Asia, and the lobbies of Yangon's handful of smart hotels are full of foreign businessmen who sniff profits on the winds of change.

Myanmar's own citizens have not yet seen any economic benefit from the new government, aside from pensioners and civil servants whose incomes were raised last year. But the authorities are drawing up a new foreign investment law and a new Special Economic Zone regime that they hope will encourage job creation by international companies.

Even if Western sanctions are lifted soon, though, allowing US and European companies to invest in Myanmar and allowing its banks to carry out international financial transactions, "we will not see an overnight El Dorado," cautions one Western diplomat.

"The most important thing is that the foreign investment climate be transparent and predictable," says one local economist with inside knowledge of policymaking who asked not to be identified by name. "This means that we have many problems to solve. All the systems we have used for 60 years need to be changed."

The government has made a start on economic reforms by unifying the exchange rate. But it has yet to tackle the antiquated and isolated banking system – most of Myanmar's economy works on cash – let alone start building the sort of independent judiciary that could rule in contract disputes or challenge the interests of the small group of crony capitalists who dominate the economy, amassing huge fortunes thanks to their close ties with the military.

Daunting practical problems confront would-be businessmen as well: Mobile phones work only intermittently, Internet connections are impossibly slow, power outages are frequent, the roads are often almost impassably potholed, and most of the railroads, built more than 100 years ago, are in disrepair.

Perhaps even more seriously, the country's workforce suffers from an acute shortage of skills and education.

"Everyone is talking about democracy and change, but we don't have the institutions we need, and we don't have the knowledge," complains the economist. "We should have an advantage as a latecomer, being able to learn from other countries' mistakes. But we can take that advantage only if we know what happened in other countries, and almost nobody here does know."

"There is a danger that the reforms will founder because the capacity to conceive and implement them is so limited," agrees Steinberg. "That, rather than opposition to reform, could be the real danger to the country."

An 'unbelievable' tipping point

Opposition to the reforms does undoubtedly lurk in high places; hard-liners in the military are keeping their counsel at the moment, but how long will that last? The generals might accept that the opposition's landslide victory at the recent by-elections was the price the country had to pay for rapprochement with the West, but if future economic reforms strike at corruption and threaten the military's economic interests, will they be prepared to pay that price, too?

The 2008 Constitution gives the Army the legal right to take the national reins again in the event of an ill-defined "emergency," but for the time being, that possibility seems remote.

"We've reached the tipping point," says Khin Zaw Win. "It would be very costly for anyone who tried to turn the clock back now, and I don't think it is in the realm of the possible anymore."

Looking back on a year of reforms, and forward to the further liberalization that the government has promised, one young journalist captures the mixture of bewilderment and hope that the changes have stirred in so many of her fellow citizens: "It's unbelievable," she says. "But I believe it."

[Editor's note: Our correspondent in Yangon could not be identified for security reasons.]