The rise of an economic superpower: What does China want?

Loading...

| Beijing

It had been billed as a friendly exhibition game in basketball-crazy Beijing, between the Georgetown University Hoyas from Washington, D.C., and the Chinese Army's Bayi Rockets. But after some blatantly biased Chinese refereeing and unashamedly aggressive play by Bayi, it ended in a bench-clearing brawl, with Chinese fans in the Olympic stadium throwing chairs and bottles of water at the Americans.

Some foreigners in the crowd that hot night in August were tempted to see the melee as nothing less than a metaphor for China's role in the world today: contempt for the rules and fair play, crowned by a resort to brute strength in pursuit of narrow self-interest.

You certainly don't have to look far for examples of China doing things its own blunt way no matter how much Western sensibilities are offended.

Just in recent months, Chinese state firms were caught negotiating arms deals with Col. Muammar Qaddafi's besieged regime in defiance of a United Nations embargo, Beijing leaned heavily on South Africa not to give the Dalai Lama the visa he needed to attend Desmond Tutu's 80th birthday party, and Chinese diplomats vetoed a UN Security Council resolution condemning the deaths of nearly 3,000 civilians at the hands of Syrian troops.

And that's not to mention the Chinese government's habit at home of locking up lawyers, human rights activists, artists, even Nobel Peace Prize laureates for speaking their minds in ways that would be quite normal in most of the world.

China's economic rise and its newly amplified voice on the international stage unnerve people and governments across the globe, despite Beijing's best efforts to assuage their fears. Bookstore shelves in America and Europe offer titles such as "Death by China" and "When China Rules the World." Edward Friedman, a political science professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, echoes some other observers when he goes so far as to call China's rise "the greatest challenge to freedom in the world since World War I" aimed at "making the world safe for authoritarianism." But does China really want to overturn the US-led post-World War II international order – the very system that has allowed the country to flourish so remarkably? And if the men at the top of the Chinese Communist Party are indeed so minded, could they, or those who come after them, ever succeed?

KUNG FU PANDA AND INNER PEACE

Ordinary Chinese – from unschooled peasant farmers tending rural rice paddies to get-ahead young computer engineers in Beijing – have been brought up to see their country as benign, and genuinely don't understand how foreigners can see China as a threat. China is the most populous country and the second-biggest economy in the world, they know, but they point out that the average person here makes only 1/10th of what the average American makes. And most of the country is decidedly third-world.

China is modernizing its military but still finds it a strain to keep a destroyer, a frigate, and a supply ship on international antipirate duty in the Gulf of Aden. Compared with the ability of the United States to fight two major wars and keep six full-scale fleets afloat at the same time, China's military power – even with the world's largest standing army – is puny.

In general terms, most China watchers in the West agree. What China wants is pretty straightforward and unexceptionable: to be prosperous, secure, and respected.

"We'd like to be an equal partner on the world stage, and we want the Chinese people to enjoy prosperity," says Wu Jianmin, a former ambassador to Paris and now an adviser to the Foreign Ministry. "For that, international cooperation is indispensable; China is not so arrogant as to say that it's our turn now to run the world our way."

Rarely in its history has China looked very hard or long at the rest of the world. Admiral Zheng He led exploratory fleets as far as Africa in the 15th century, but subsequent emperors were content to sit on the throne of the Middle Kingdom, at the center of their universe, and focus on their own lands. China spent a hundred years of submission to Western powers following its defeat in the 19th-century Opium Wars, and it was mired in decades of disruption before and after Mao Zedong's 1949 Communist takeover.

Only with its newfound wealth has Beijing found itself with a major role on the world stage.

"It's a very big challenge to restructure our relations with the world while retaining its trust," worries Zhu Feng, a professor at the School of International Studies at Peking University.

So, as China rises, its leaders are going out of their way to try to reassure the world that their success is, in a favorite official phrase, a "win-win" prospect for everybody. So nervous were policy-makers here about upsetting foreigners that they scotched their original formulation of China's future – "peaceful rise" – as too threatening. Instead they settled on "peaceful development."

Last month the government issued a 32-page white paper full of comforting words explaining what it wants the world to understand by that phrase.

"There have been misunderstandings about China's foreign policy," said Wang Yajun, the Communist Party's top foreign-policy wonk, presenting the document to the press. "There have indeed been suspicions."

The white paper's key message is that China threatens no one, that its rise will contribute to world peace, and that "the central goal of China's diplomacy is to create a peaceful and stable international environment for its development. China could become strong in the future. Yet peace will remain critical for its development, and China has no reason to deviate from the path of peaceful development."

"China does not want to, nor will China, challenge the international order or challenge other countries," insisted Mr. Wang, pointing to the white paper declaration that China has "broken away from the traditional pattern where a rising power was bound to seek hegemony."

Not everyone believes this, even in China. "Humanity is making progress," argues Wang Xiaodong, a prominent nationalist ideologue whose views are proving increasingly influential among the Chinese public, "but not so much that China will be unique in human history. The idea that China will develop its power but not use it is diplomatic verbiage."

China's Southeast Asian neighbors might well agree. Until earlier this year Beijing had been unusually assertive in pushing its competing territorial claims in the South China Sea, worrying smaller nations. But the way it has eased off in recent months in the face of complaints suggests it cannot do just as it likes.

"China tests the water constantly, and when they don't get what they want they tend to back down," says Bonnie Glaser, a senior fellow at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington. "As they develop their military capacities, they have to be very careful not to use them in ways that scare the neighbors."

The Chinese government's need to explain itself stems partly from the system's chronic secrecy: Outsiders do not even know when the ruling Standing Committee of the Communist Party's Politburo meets, let alone how its nine members reach decisions or what those decisions are.

At the same time, some observers suggest, there is not always a coherent answer to the question of why China does what it does. The Chinese government is not a monolithic force; pressure groups and cliques from the military to provincial governments have their own interests and can sometimes push aspects of foreign policy their way.

"They don't have a clear and well-defined road map of how to achieve their goals long term other than to pursue development as they have done," says Michael Swaine, a China watcher at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace in Washington.

Nor, frankly, do foreign affairs seem to figure very high on Chinese leaders' agendas. "International questions are an afterthought," says Francois Godement, founder of the Asia Centre, a Paris-based think tank. Instead, for a Communist Party whose overriding priority is to stay in power, domestic problems threatening social stability at home are infinitely more important.

"We have to change our unsustainable development model into a sustainable one" less dependent on high pollution, low-value exports, argues Mr. Wu, the foreign-ministry adviser, "and we have to narrow the disparity between rich and poor."

"China will be preoccupied for a long time with its domestic agenda," agrees Professor Zhu. "If you want to handle complex relationships, the starting point is to get yourself in the best possible shape. It's like Kung Fu Panda says – you need inner peace."

CHINA IS RICH BUT LONELY

As the big guns of the Democratic Republic of Congo's mining sector gathered last month at a smart lakeside hotel in the copper capital of Lubumbashi, some important new players were notably absent from the conference. Those who attended said they weren't surprised that no Chinese company had sent a delegate; the Chinese rarely mix with their mining colleagues, they explain.

But a visit to a local casino, heavily protected behind high, razor wire-topped walls, is evidence enough that the Chinese are indeed in town, and with money to spend: The clientele in the smoky, air-conditioned chill is almost exclusively Chinese – crowded at roulette tables and playing blackjack and poker, with mounds of chips in front of them.

These men are part of a growing Chinese presence in Congo that has already flexed some impressive economic muscle. Chinese companies are behind two billion-dollar deals, now in the works, to buy two large copper mines near Lubumbashi. Across the African continent, others like them are engaged in China's most dramatic drive for friends abroad, seeking to secure the oil, minerals, and other raw materials that China's still-booming economy needs.

"China's financial support on the continent gives African countries a choice" between East and West, says one Chinese activist at a nongovernmental organization following Beijing's African adventure, who asked not to be identified.

China's financial muscle has been key to its growing influence in the Democratic Republic of Congo, where Beijing signed a $6 billion minerals-for-infrastructure deal in 2009. Congo's traditional Western partners don't have the ready cash for the mammoth task of rebuilding the war-ravaged country, says Congo's communications minister, Lambert Mende, so "China is very important."

In return for 10 million tons of copper and 600,000 tons of cobalt, China will build roads, schools, hydroelectric dams, and hospitals. Half the deal is a barter, which means that it adds less to the country's foreign debt burden.

"Whether [the deal] will prove to be more effective than the Western model in the long term remains to be seen," says Lizzie Parsons of the Global Witness pressure group. Among unanswered questions: whether money will be siphoned off corruptly, whether all the infrastructure will be built, and what impact fluctuating mineral prices will have on the deal.

Orange construction vehicles from China are already a common sight at roadworks all over the capital, Kinshasa, and more and more people are doing business with Chinese firms. The experience is not always a pleasant one, according to one Western businessman who has worked in Kinshasa for nearly two decades.

"When you see a Chinese come into your office you prepare yourself for a fight," he says. "You are rarely happy at the end of negotiations. They don't show respect or politeness, and there is no feeling," he complains, adding that he rarely builds with Chinese clients the sort of personal relations he enjoys with Congolese or Western businessmen.

The Chinese are sharp, though, and Congo's traditional Western partners feel a little threatened by them, especially in light of Chinese firms' close relationship with the Congolese government, acknowledges the Western businessman.

"We are aware of their strength," he says. "They are protected; they can drive a car with no plates and no one stops them. You try doing that and see what happens."

Another country keen to keep the China card up its sleeve, especially as its relations with Washington turn sour, is Pakistan, whose leaders have recently been trumpeting the two neighbors' "all weather friendship."

China's efficient work on the ground in Pakistan (see related story on page 29) has earned it a warm welcome: A Pew survey last year found 85 percent of Pakistanis had a favorable view of China, versus only 17 percent who were similarly disposed toward America, Pakistan's major donor.

Pakistanis remember that China has provided arms when Washington refused them in the past, but Beijing appears reluctant to involve itself too deeply in security affairs today: Business is good, and Pakistan is a big market for Chinese electronics, motorbikes, toys, and food, but China's leaders seem cautious about committing too deeply to Islamabad, say ob-servers in Beijing.

On the other side of the world, in Brazil, it's a similar story. China overtook the US as Brazil's largest trade partner in 2009 on the back of huge purchases of oil, soybeans, and iron ore; Brazilian exports to China grew 18-fold between 2000 and 2009.

But "our relationship with China is one of almost only commerce and investment," says Roberto Abdenur, a former Brazilian ambassador to both Beijing and Washington.

"With the United States it's cultural and political – the two countries share many interests that China doesn't," such as the promotion of human rights, democracy, and transparent governance, he adds.

Indeed, for a government that says it is generally content with the current world order, Beijing is on unusually good terms with regimes cast out by that order, such as those ruling Iran, North Korea, Sudan, Burma (Myanmar), and Zimbabwe.

"By making friends with dictators, China challenges the [global] democratic system and works at cross purposes to the international mainstream," complains Mao Yushi, a well-known reformer who has mentored many of China's leading economists.

This does not inspire confidence in Western capitals but is less of an issue in developing countries, whose own experience with Western governments – under their rule or trading with them – has often left them feeling seriously hard done by.

China has fewer opportunities to exert international political influence commensurate with its economic clout. That's partly because few governments around the world, and even fewer electorates, regard China's repressive, authoritarian one-party system as a model to be admired or imitated, regardless of its economic achievements.

Though China's readiness "to voice different opinions from the only country in the world that has had a say up until now ... is attractive to other nations," says Gong Wenxiang, a professor at Peking University's Journalism School. "I can't see people being happy with a very strong power often supporting dictators. That is not a positive image."

"China is a power in terms of its resources, but it's not a power in terms of its appeal," adds David Shambaugh, director of the China Policy program at George Washington University. Deficient in soft power, "it's not a model, not a magnet others want to follow."

Nor does Beijing show much sign at the moment of seeking to push any particular model of governance or political mind-set, which is music to the ears of men like Mr. Mende, the Congolese communications minister. "We don't believe in that trend of Western powers mixing with internal affairs of countries," he says. "We don't like people giving us orders. China is more about respecting the self-determination of their partner."

That hands-off approach also steers the country clear of alliances that might enmesh Beijing in the costly defense of other people's interests. Even those Pakistani officials who would like to play Beijing off against Washington recall that not once has Beijing stepped in to help Pakistan in any of its wars with India, all of which Pakistan lost.

"China wants to make the deals but not to shoulder responsibilities," says Zhu, the Peking University international relations scholar. "We are far from ready, psychologically, to make ourselves a dependable power."

The government's recent white paper acknowledged as much: "For China, the most populous developing country, to run itself well is the most important fulfillment of its international responsibility."

Recent events in Libya illustrate how far China is from playing a creative international diplomatic role. Throughout the crisis, Beijing was a passive, reactive bystander, going along with Western intervention. But, focused on protecting its oil interests above all else, it was the last major power to recognize the new Libyan government. That cautious attitude was on display again last week in China's reluctance to contribute as heavily to the eurozone's bailout fund as European leaders had hoped it would. China was not, after all, going to save the world.

"China's diplomacy is cost-benefit-oriented, not dealing in terms of global public goods," argues Professor Shambaugh. "It's a very self-interested country, looking after themselves."

One result of that attitude? "China is rising, but we are a lonely rising power," says Zhu. "The US has alliances; no one is an ally of China's."

NEIGHBORS SAY, 'NEVER'

Vietnam was once an ally, when Hanoi was fighting the Americans, but not any longer.

"Jamais," read T-shirts that Vietnamese protesters donned last month, "Never." The slogan recalled Ho Chi Minh's forceful response when he was asked by a French interviewer whether Vietnam would become a Chinese satellite after the war. It still expresses the popular, centuries-old anti-Chinese feeling that runs deeper than any shared allegiance to communism.

The demonstrators were protesting the aggressive way they said China is pushing its claim to the Spratly Islands, a cluster of rocks in the South China Sea that Vietnam also claims. Both countries are eyeing oil and gas reserves under surrounding seas. Chinese naval vessels have arrested more than 1,000 Vietnamese fishermen in disputed waters this year, according to the Hanoi fisheries authorities.

China is embroiled in similar territorial disputes in the South China Sea with several other regional powers, and they all sent their defense ministers to Tokyo last month to discuss ways of deepening their cooperation.

"China's aspirations to be a regional leader are meeting resistance from other states already," says Hugh White, a former Australian defense official. "Beijing would like to exercise a soft, consensual leadership, but they won't be able to achieve it" because none of China's neighbors would accept it.

China's key local priority abroad is to prevent Taiwan from declaring independence and to eventually unite the island with the mainland. But Beijing's escalation of its territorial claims to almost the whole of the South China Sea and its rapid modernization of a navy to enforce those claims alarm Washington's and China's neighbors. Fifty percent of world trade is shipped through those waters.

"China's one overriding focus is to challenge US ability to project its power in the western Pacific," says Mr. White. "They want to be able to sink American aircraft carriers."

According to senior US naval officers, China may soon be able to do just that, using its new antiship ballistic missiles to enforce "anti-access and area denial" close to Chinese waters. Using such weapons as part of a defensive strategy, "China can reduce US strategic options very significantly," warns White, should Washington ever want to come to the aid of Taiwan or other allies in Southeast Asia.

That puts China's neighbors in an awkward position. All of them, from Japan to Laos, know that their economic future depends on China, Asia's powerhouse. China's success will be their success. But for centuries, countries such as Vietnam and Korea lived under the yoke of a successful China, points out Linda Jakobson, a researcher at the Lowy Institute in Sydney, Australia, "and nobody in the region wants to go back to that,"

PROFIT MOTIVE OR GEOPOLITICAL MOTIVE?

If China's political leaders know that they still lack what it takes to play a decisive role in world affairs, Chinese business titans are even more aware of their limitations.

"There is a perception that China is buying up the world," says Andre Loesskrug-Pietri, a Franco-German businessman whose private equity company in Beijing helps Chinese firms make foreign acquisitions. "But it's not true."

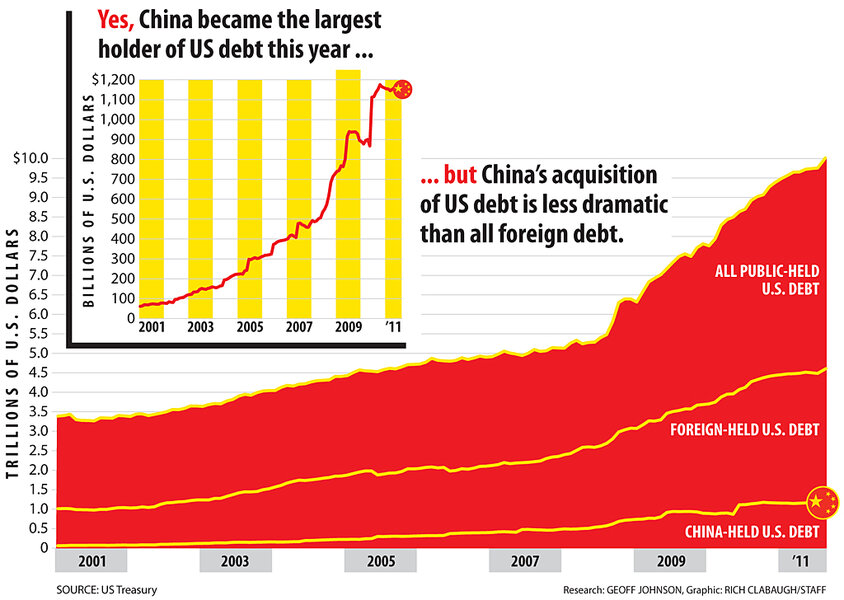

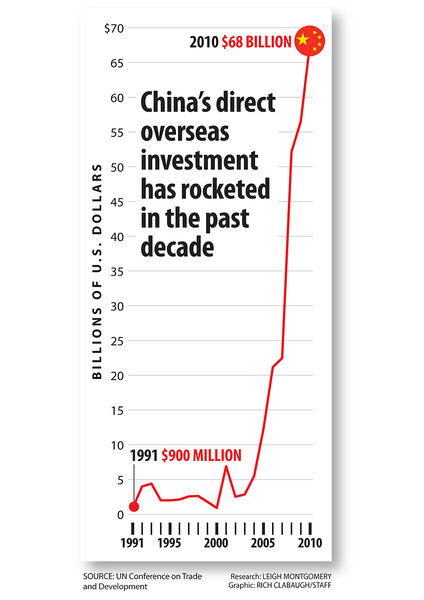

Chinese overseas investment is growing by leaps and bounds, doubling annually, and high-profile deals such as Lenovo's purchase of IBM's personal computer division grab headlines. But China's total foreign direct investment remains low – about the same as Denmark's (1 percent of the global total compared with the 22 percent US share). And 60 percent of overseas deals are for resources, such as stakes in oil-shale fields in Canada, coal mines in Australia, gas fields in Argentina, and copper mines in Zambia.

Very few Chinese firms have the skills and experience needed to become competitive multinationals, says Thilo Hanemann of the Rhodium Group in New York and author of a recent study of Chinese foreign investment. "What corporate China is doing at the moment is catching up," he explains. "Chinese companies are disadvantaged in technology, staff, human resources, brands, and intangible value."

They also have to learn new ways of doing business, very different from their habits in China, where the key to success is often a close relationship with the government officials who can offer easy credit and light regulation – for a consideration.

"The longer I live here, the more relaxed I am about the so-called threat perceived in the West of China taking over the world," says Mr. Loesskrug-Pietri. "Many Chinese investors are unfamiliar with foreign business cultures, and we are still a long way away from seeing executives and companies that are truly global."

Not one of the Top 100 global brands ranked by Businessweek magazine and the consulting company Interbrand comes from China. Though 61 of the top Fortune 500 companies are Chinese, hardly any have any foreign directors; most are state-owned companies whose leaders are named by the Communist Party. And most of the Chinese companies going abroad are doing so, says Loesskrug-Pietri, to acquire what they need in order to compete better in the market they find most attractive – China.

A handful of Chinese firms are developing a genuinely global presence: Lenovo is one; Huawei, a telecom-networking firm selling its products in 140 countries, is another; Haier has begun to sell a significant number of its household appliances in America and Europe, as well as in Asia. And the larger, reputable private companies stretching themselves internationally tend to get high marks from their foreign partners.

"I've been very impressed," says Henri Giscard d'Estaing, chief executive officer of Club Med. The French tourist resort owner sold a 10 percent stake to Fosun, a Chinese conglomerate, earlier this year. "They behave like normal long-term share-holders; they've concluded that we know our business and they let us get on with it. Doing business with Fosun has been more banal and more basic than most people would think" business with a Chinese firm would be, Mr. Giscard d'Estaing adds.

Where some critics of Chinese foreign investment "perceive state motives, or some kind of geopolitical motivation ... I see a commercial motive and profit-oriented behavior," says Dan Rosen, a visiting fellow at the Peterson Institute in Washington.

But very few Chinese companies feel ready to go abroad, despite government encouragement.

"They often feel insecure. They know they don't know how things work, and they are cautious about messing up existing operations," says Loesskrug-Pietri.

Some of them also have good reason to be nervous about the reaction they might provoke. "As Chinese companies go global they encounter so many suspicions," complains Wu. "This is not a good sign."

The private company Huawei, for example, in the past three years, has been blocked three times on national security grounds from doing deals in America, after critics claimed the company has links with the Chinese military. Huawei has always denied that, but only after the third setback did the firm disclose its ownership structure and board membership in a bid to be more transparent.

Even when that kind of secrecy is not a problem, Chinese investors abroad are running into increasingly open anti-Chinese sentiment. In Brazil, where local manufacturers claim that cheap Chinese imports of everything from toys to cars to industrial machinery have cost the Brazilian economy 70,000 jobs, the government recently slapped a protectionist tax on foreign vehicles aimed at the Chinese-made Chery, the cheapest fully accessorized car on the market at $13,600.

And as Chinese investors express interest in Brazilian farmland, parliament is debating a law that would allow Americans and Europeans to buy land, but not Chinese.

In Zambia, where Chinese investments in copper mines top $2 billion but where Chinese employers have made a bad name for themselves, the presidential election this month was won by Michael Sata, who has made his career out of China-bashing. Even in Burma, one of China's closest friends in Asia, the government last month suspended a controversial Chinese dam project amid a rising wave of popular resentment against an overwhelming Chinese business presence in the country.

A SHALLOW – NOT SUPER – POWER

"China really has to know how to navigate these stormy waters," warns Zhu. "The West overreacts a bit to our rise, but we have to pay more attention to the fact that we are the ones causing the disturbance."

"We are newcomers, and people are usually suspicious of newcomers," says Wu. "They also have a lot of suspicions about the Communist Party, which creates an ideological barrier. But if our actions match our words, over time we can build trust."

China is a "shallow power" for the time being, argues Shambaugh. "China is strong in the economic realm but very weak in the security realm, and without much soft power" such as cultural influence, or the ability to persuade other countries to imitate it.

"As long as the Western democracies remain reasonably strong and prosperous," adds Mr. Swaine at the Carnegie Endowment, "China will not drive the world economy sufficiently to make other countries align themselves with it. In any foreseeable time frame I do not see China becoming the sort of global superpower that the US became after the war."

And anyway, he points out, such questions will be moot for many decades. "The generation of Chinese leaders that will decide whether they want to be that kind of superpower," Swaine believes, "has not been born yet."

• Contributors to this article include: Issam Ahmed in Aliabad, Pakistan; Taylor Barnes in Rio de Janeiro; Whitney Eulich in Boston; Scott Harris in Hanoi, Vietnam; and Jonny Hogg in Kinshasa and Lubumbashi, Democratic Republic of Congo.