Hilltop city in Japan becomes a refuge for earthquake, tsunami survivors

Loading...

| Hitachi, Japan

The small industrial city of Hitachi emerged relatively unscathed from what Prime Minister Naoto Kan has described as Japan’s “worst crisis since the Second World War," making it something of a refugee center for evacuees from cities to the north.

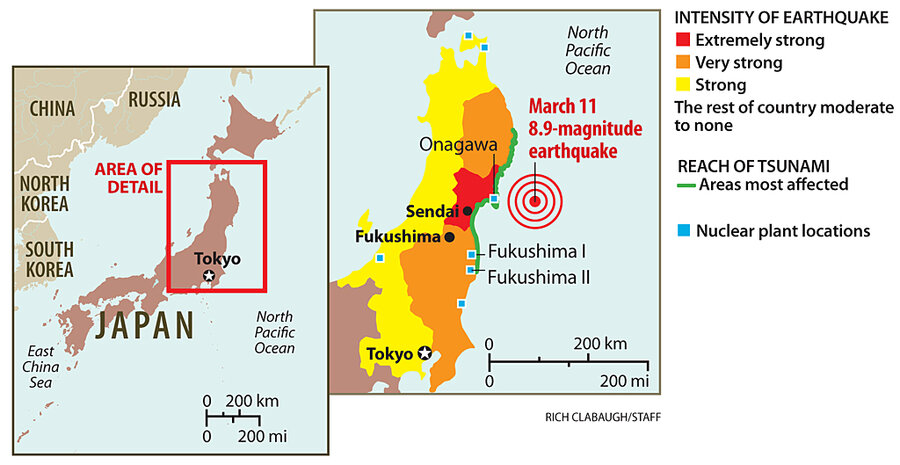

The city's resilience in the face of a still-unfolding tragedy that killed at least 10,000 people and destroyed whole towns on the northeast coast is credited to its topography. Most of the town's residencies sit on higher ground than surrounding areas swept away by the 30-foot tsunami that followed Friday's temblor, now estimated to have been magnitude 9 (up from initial reports of magnitude 8.9).

Even if this city on the southern edge of the quake-affected zone has patchy access to water and electricity, its citizens escaped relatively unscathed – bar some cracks in roads and buildings. Other towns are not so fortunate. Driving along Japan's northeast coast near the epicenter of the quake, observers can see towns full of debris and collapsed houses.

“We were so lucky really. I haven’t heard of any serious injuries amongst people I know,” says a security guard keeping watch outside the Hitachi Futo shipping company’s lot in the city’s harbor.

Behind him, brand new Mercedes-Benz cars are stacked on top of each other like toys in a child’s playroom, recently arrived from Germany but tossed around and mangled by the tsunami. The port is one of two main entry points for the luxury cars, which will now never reach their intended customers.

Escaped families

Aftershocks continue to rattle the region – and set residents on edge. The government has warned of a 70 percent chance that another 7-magnitude quake could hit at any moment.

But at the Hitachi Hotel Crane, families escaping the devastation of the worst-affected areas are simply happy to have a dry place to stay, despite a lack of running water – although the unfolding crisis at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station, only 60 miles away, weighed heavily.

“There’s no electricity where we were and it’s still cold at night, so it feels great to be here,” says a man checking into the hotel with his young family. “I’m still worried about what could happen at the nuclear plant though. There are so many things I want to say, but I can’t put them into words right now.”

In nearby Oarai, a small fishing port, the aftermath of the tsunami was visible everywhere: an earth mover flipped completely upside down, boats sitting in places they were never intended to be, and furniture from houses and businesses lined up along the still-wet roads.

With supplies still scarce, motorists were also lined up today for hundreds of feet waiting for a gas station to open at 5 p.m. At the front of the queue was a car belonging to a young lady who said she had been waiting for hours. Once gasoline did arrive at the station, she said she would only be able to get five gallons due to rationing.

Yet, she says, she knows how much more fortunate she was than tens of thousands of others nearby.