For some US gymnasts, success is a family affair

Loading...

| Beijing

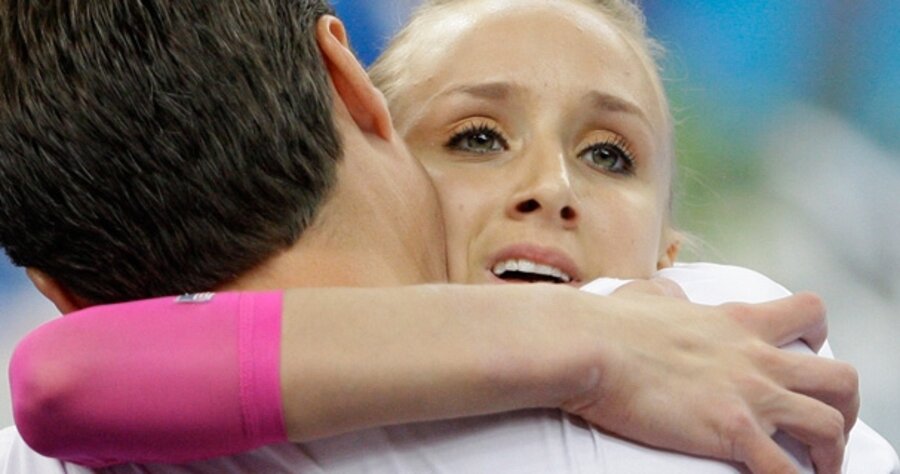

In the moments after American gymnast Nastia Liukin won the most prized title in individual gymnastics – the Olympic all-around gold – her coach added an asterisk.

As of that Friday afternoon, he noted, Nastia still only had two medals from her Olympics – the all-around individual gold and an all-around team silver.

“I’ve got four,” he smiled, counting two golds and two silvers from the 1988 Games.

Valeri Liukin, Nastia’s coach and father, wanted to make one thing clear: Papa Liukin still had bragging rights. Nastia returned the grin. “I’m still chasing him.”

On Monday night, she caught him, gaining a silver on the uneven bars after winning bronze on the floor Sunday. And on Tuesday, she surpassed his record with a silver for her balance beam routine.

The exchange, however, was a glimpse into the peculiar life of three elite US gymnasts whose coaches are also their parents, combining dinner tables and medal tables. Liukin’s Olympic teammate, Chellsie Memmel, is coached by her father. Jana Bieger, who just missed making the team, is coached by her mother.

For the Liukins, it has been a balance worked out over years, at times huddled over Valeri’s notes, trying to decipher the hand holds and releases for a new routine from his incomprehensible string of letters, at times screaming at each other in Russian.

Yet after training sessions that can sometimes leave father and daughter overheated, the needle of their inner RPM pushed into the red, it is their shared commitment to a single goal that binds them when all else frays.

“We’re both perfectionists,” says Nastia. “I won’t give up until it’s as good as I want it to be.”

After Nastia had won gold in the all-around Friday, a smile of obvious pride began to twist Valeri’s lips: “She’s a tiger.”

In the fulfillment of these Games, the hours invested by both of them in their Dallas gym have taken the fond glow of retrospection.

Nastia recalled the first time her father suggested the uneven bar routine that has now won her two medals – the silver in the apparatus final Monday and the all-around gold, where it staked her to a lead that teammate Shawn Johnson could not catch.

Months ago, Valeri had left out a sticky note for her to find. It was a list of letters: D, D, D, E, D, E, E…

She asked him what it meant. When he explained, her first reaction was: “Wow, that seems really hard.”

It is. With a 7.7 difficulty score, it is tied for the hardest uneven bar routine in the world. Her second reaction was: “I would give everything to do that routine.”

Now she has – Valeri’s tiger loosed on the gymnastics world.

Yet the past few years have not been easy, each acknowledges.

“When she was little, she was a little soldier” following every instruction, says Valeri. “But now, she is a more mature gymnast – she understands a lot more because she is a very smart girl.”

In other words, she is a teenager, and she tends to have her own opinion.

“The past few years have gotten a little harder,” Nastia says. “There are days when we disagree on things.”

Andy Memmel, Chellsie’s father and coach, can commiserate.

The friction between he and Chellsie comes “when we’re not communicating with each other,” he says. Citing one instance, which actually led to an injury, he adds: “I told her not to do something, and she did it anyway.”

Such disagreements are not unexpected between coaches and young, high-level athletes. But the Liukins have to sit together at dinner, too.

In the end, Nastia always has gratitude to fall back on. Her father and mother moved from Russia to the United States when she was two, feeling that the US held more opportunities.

“I have so much respect for them doing that, because they did it for me,” she says.

Yet there are moments when Nastia is also grateful that her mother – formerly Anna Kotchneva, a world-champion gymnast in her own right – seems to be wired a little differently from her husband and daughter.

“It’s nice to have someone to even things out,” says Nastia. “You get to this level and having a dad as a coach makes things difficult.”

It is, Nastia suggests, a softer touch, yet no less meaningful. In the days before she came to Beijing, Nastia says she made a pin-up board of things that inspired her. One day, Anna tacked an addition to the board: One of Valeri’s gold medals.

“It gave me that extra motivation,” she said after the all-around.

Andy Memmel still asks himself every so often if he is doing the right thing in coaching his own daughter. “I don’t want to think that she could have advanced herself further by going somewhere else,” he says. “I don’t want to let her down.”

In Valeri’s case, that concern is equally real and usually literal. At 18, Nastia has already lost nearly two years of her career to injury. When she is on the uneven bars, he stands beneath her, spotting her, visibly nervous.

Nastia is fragile, he said in a conference room of the gymnastics venue before the team competition began. Nastia sat in front of him, journalists pressed around her, arms extended like the spokes of a bicycle wheel, his daughter at its center. “You worry about every single thing,” he said – the complexity of her uneven bars routine, the danger of her vault, how she will handle the pressure.

Then, for a moment, he shook his head, no longer the coach or the Olympic medalist, but the father of a teenage girl: “Being a gymnast is so much easier than being a coach – much less a father.”