In medals race, more countries in running

Loading...

| Beijing

Seventeen days from tonight’s opening ceremonies, America’s post-Soviet reign atop the Olympic gold-medal table is expected to end – and that could be just the beginning.

Competition is changing more thoroughly than at any time since the collapse of the Soviet Union. China is at the head of a number of countries, from Britain to Australia, significantly ramping up spending.

This Olympics will mark only the start of the trend. China’s massive effort to win these Games is just now getting up to speed. It is tipped to win the gold-medal table here. By 2012, it could dominate – following a longstanding trend of great powers vying for Olympic clout that mirrors their diplomatic weight.

Add to this the rise of second-tier nations like Britain, and America will increasingly be squeezed from both ends.

It suggests an era of unprecedented equality among Olympic nations. The days of one nation winning 100 medals – as the US did four years ago in Athens – “might be a part of the past,” says Steven Roush, chief of sport performance for the United States Olympic Committee (USOC).

The picture he paints is something like cold-war-lite: Three nations competing at the top of the medal table, but the distance between them and the nations after them increasingly diminished. Russia and the US will repeat their cold-war roles, with China standing in for East Germany and perhaps outstripping them both.

Home-field advantage

The Chinese assault on the medal table is overwhelming. Home-field advantage generally helps the host nation, and in recent Olympics, China has already been improving its performance. It is winning medals in sports at the margins of the Olympics, and also among women.

In Athens, where China finished second, women won more than half the nation’s gold medals. American women won one-third of the US total.

Olympic historian David Wallechinsky calls events like shooting and women’s weight-lifting “soft targets,” not to demean them but because the amount of talent competing in these sports is comparatively less than in sports like track and field and swimming. That makes it easier for new athletes to break through and medal.

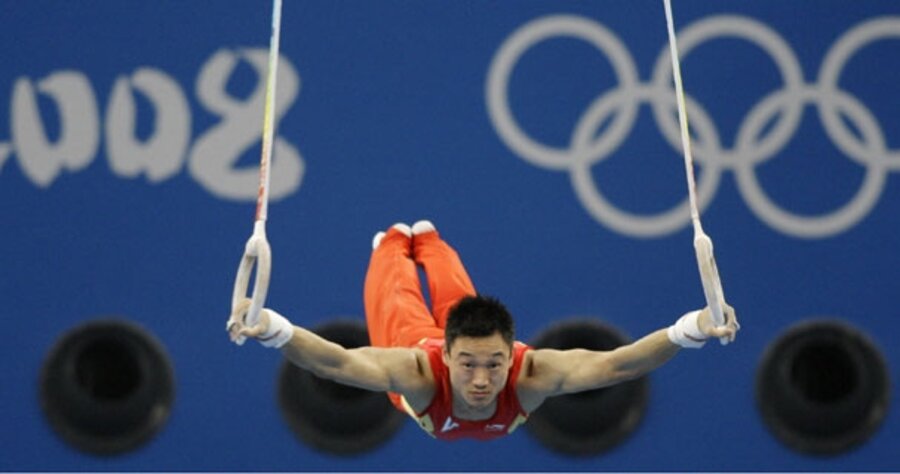

Yet this means that the Olympics’ two great new sporting rivals might hardly see anything of each other in the fight for medals – the notable exceptions being gymnastics and perhaps women’s volleyball or soccer.

In America’s best events, swimming and track and field, it is possible that China might not win a single gold.

What is perhaps most worrying for American Olympic officials is that this will almost certainly not be the case from 2012 onward.

Project 119

Eight years ago, China began Project 119, a $744 million bid to win in Beijing. The program is founded on the idea China can not fully overtake the US and Russia until it becomes better at track and field, swimming, and water sports such as rowing and canoeing/kayaking.

When Project 119 began, those sports accounted for 119 of 300

gold medals. Now they account for 122.

One year ago, however, the vice president of the Chinese Olympic Committee had to admit that Project 119 was not progressing as planned. “Every way you look at it, we are far behind,” said Cui Dalin. Hurdler Liu Xiang and swimmer Wu Peng are notable exceptions.

But the USOC’s Mr. Roush cautions against reading too much into China’s performance in swimming and track and field at these Games: “There were unrealistic expectations that by throwing money, they would instantly be able to progress,” he says. “In the more developed sports, you don’t just shoot through the rankings.

“Project 119’s effectiveness might not be seen in 2008, but it will be in 2012, ’16, and ’20,” he adds. “My sense is that China is in it for the long haul.”

“That is what keeps me up at night,” he says.

At the palatial Shunyi Olympic Rowing-Canoeing Park, there is already a hint of what could come. The facility is an unambiguous statement of Project 119’s intent. “It is the single most costly canoe/kayaking venue anywhere in the world,” says Chris Hipgrave, a coach for the US team, a note of awe in his voice.

Since the advent of Project 119, the Chinese have gone from makeweights in world flat-water canoeing to medal contenders, hiring top coaches from abroad and building world-class training facilities like Shunyi nationwide.

“You go back a few years and they never had a presence in the sport,” says David Yarborough, executive director of USA Canoe/Kayak. “Now you do see them emerging as a federation to be reckoned with.”

The sport, he believes, is perfectly suited for the strengths of the Chinese sports system. “You learn the technique, the stroke rate – it’s all the measurable, trainable parts of Olympic sports that you can take from the lab to the water,” says Mr. Yarborough. “You can go out and preselect a body of athletes.”

Yet the white-water version of the sport also suggests how progressing in a sport is sometimes more than simply a matter of funding. Christian Bahmann won the white-water kayaking World Cup in 2005. When the German failed to make the Beijing Games, the Chinese came calling. He is now a coach here.

Styles of training

There have been successes in the program before and since. Last year, China won its first white-water kayaking medals at a World Cup event. But Mr. Bahmann’s admiration for the work ethic of Chinese kayakers is tempered by frustration.

“It’s not the quantity of the training, it’s the quality,” he says. “They think that if you train and train and train, it is enough.”

Unlike flat-water racing, “you are dancing with white-water,” says Ben Kvanli, a US white-water canoer. Adds Yarborough: “It puts a premium on all the intangibles – on all the things you can’t teach.”

Mr. Kvanli suggests the Chinese have done an admirable job of choosing whitwater athletes. “The athletes have been more fun-loving than I would have expected them to be,” he says. “It’s not the East German look you might have expected.”

For Bahmann, it is difficult to get the athletes to think outside the boat – simply sitting down and watching other racers, for example.

“I have no bad word about the athletes here, but it’s not easy for them to have their own opinion,” he says. “This is the thing in whitewater: You always have to make your own decisions.”

Still, Kvanli is impressed by the impact Project 119 has made. “Back at the world championships in 2002, they were terrible – their athletes were sitting there smoking cigarettes,” he says. “But they have done what I would have previously though to be impossible…. They are winning medals at the World Cup.”