He’d fight LA fires if he could. A former inmate shares his story from Mexico.

Loading...

| Tijuana and Mexico City, Mexico

This story is by Javier Salazar Rojas, who goes by the name @DeportedArtist, as told to special correspondent Whitney Eulich. He spoke to The Christian Science Monitor as over a thousand incarcerated people joined firefighting efforts in Los Angeles, and as President Donald Trump took office promising to expel millions of unauthorized immigrants from the United States.

Seeing the fires in LA, it brings up a lot of emotions for me. With my training and years fighting fires, when I see all that devastation, I feel like I should be there. I need to be there helping.

But I was deported.

Why We Wrote This

Incarcerated people in California have helped put out the fires in Los Angeles. One man, deported to Mexico for his crime, says he wishes he could be back on the line now.

I was born in Tijuana [in Mexico]. When I was about 3 months old, my mother brought me to Oakland [in California] illegally. I eventually got permanent residency and qualified to become a citizen. But nobody ever explained to me that permanent didn’t mean permanent. When I ended up in prison, I lost my residency. I didn’t know how it would affect me until I’d already been in prison for four years. That’s when ICE [U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement] informed me that I would be deported after serving my sentence.

I had a girlfriend for five years, and she died suddenly. I was depressed, and I turned to drugs to deal with that pain. I made some bad decisions. I was arrested in 2003 after trying to rob a convenience store, and ended up in prison with a 12-year sentence for armed robbery. I didn’t [physically] hurt anyone, but because I had a weapon with me, I received 10 extra years under a new California [sentencing] law called 10-20-life.

I started the firefighting program in prison, when I had three years left.

I remember my first fire in 2012. It was a really hot day. We were trimming the vegetation at a school – fire hazards. Around 3 p.m. when we were already really tired, the captain called us. We got on the truck, and it was the first time I was in it with the sirens blasting. We were trying to get dressed in the back so that we’d be ready when we got there.

The fire was on a hillside, a forested area behind some homes, and it was moving quickly. It was still a pretty small fire, but it was one of those that you have to get under control fast before it transforms into something serious. We spent about four hours putting it out. I was the first Pulaski – other[s] call it the hot shovel. It’s the position that goes in first behind the Hot Team. They open the passage and then the Pulaskis dig the line, taking out all the roots and underbrush. I was directing the line.

It's a lot of adrenaline, but your training keeps you steady. You run toward fires while everyone else, even animals, are running away.

I liked fighting fires because I preferred to do something productive, something that benefits not just me, but society. When I was fighting fires, I never forgot that I was a prisoner, but when you save someone’s home or save a town, people thank you. They treat you like a normal person, not a criminal, and that makes you feel good. I felt like I was repairing the bad I had done to get sent to prison, in a way.

After serving all that time with Cal Fire [California’s Department of Forestry and Fire Protection], I didn’t think they would deport me.

I served 11 years of my sentence. When I got out, they flew us [formerly incarcerated people with deportation orders] to San Diego and put us on a bus to Tijuana. I felt that it was the end of the world. Yet, here I am in Tijuana, and I’ve come to realize that in Mexico, we can have dreams, too. We can move ahead. I’ve been back for 10 years.

Sometimes it’s hard to express myself with words, and art helps me share my feelings and all that has happened and put them in an image. I’ve made murals in Playas de Tijuana, portraits of people who after spending all of their lives in the U.S. were deported to Mexico. The portraits are black and gray – we didn’t use color because it’s something sad. It represents this feeling of being kicked out of the only country you’ve known since you were a kid.

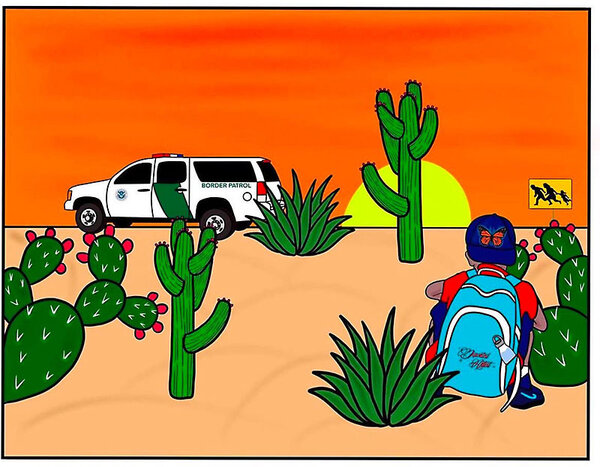

Sometimes I’m there and see people who look at the images and I see in their eyes that they understand it. Art transcends not just borders, but languages and cultures. That’s helped me a lot. When I got to Tijuana, I called myself DeportedArtist because I figured if no one spoke up for [deportees], then our situation would never change. We need to be seen and to be heard. With everything going on in the U.S. right now, the xenophobia, the racism, all the lies about the migrant community – so many people hate us. People don’t have to like us, but at the end of the day, they need us.

They want to blame the Mexicans, the Latinos, the migrants, but we are the ones who will rebuild LA.