How a Puerto Rican community battles blackouts with solar power

Loading...

| Bogota, Colombia

When Hurricane Maria battered Puerto Rico and decimated the Caribbean island’s power grid five years ago, the lights stayed on in one building in the mountain town of Adjuntas.

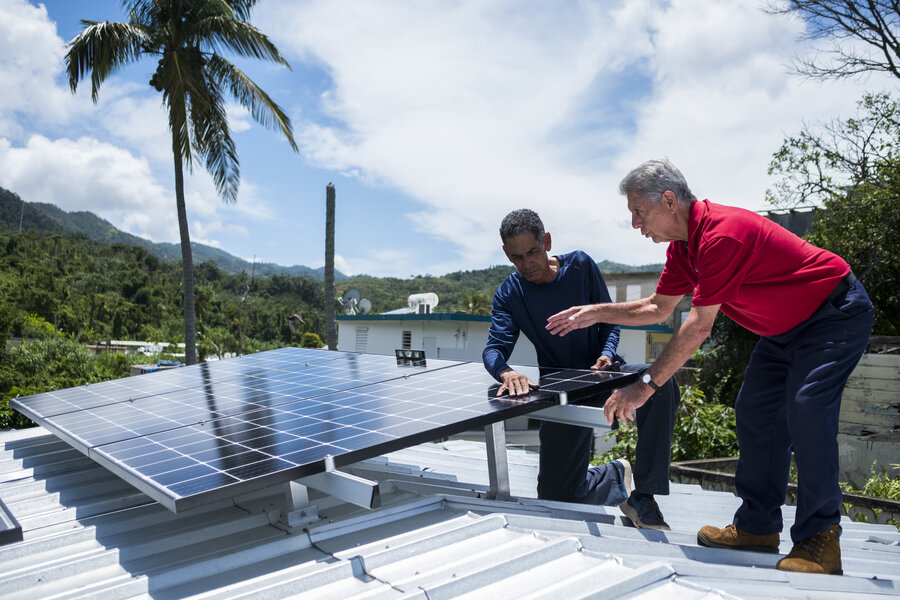

The Casa Pueblo environmental group had equipped its Adjuntas headquarters with solar panels and storage batteries – a model of green self-sufficiency that inspired the organization to launch a pioneering community-run microgrid in the town.

“We want to democratize the generation of energy ... we’re pushing from the bottom up,” said Arturo Massol-Deya, who heads Casa Pueblo, which last month finished installing nearly 700 rooftop solar panels as part of the microgrid initiative.

The panels supply 14 local shops, including a pharmacy and a bakery, and feed into a standalone network that can operate independently of the island’s creaky, fossil fuel-powered grid – providing a backup during lengthy power outages after storms.

The microgrid will also be hooked up to the national network, with any power surplus helping to reduce the community’s electricity bills.

“It’s a pioneering example of what could be the new energy set-up in the country,” Mr. Massol-Deya said of the community-run and owned initiative, one of the first of its kind in the U.S. territory of 3.3 million people.

The project has been hailed as an example of locally-led resilience in the face of more extreme weather events, including hurricanes, and of a growing grassroots movement to put energy production in citizens’ hands.

“A local community putting up the resource [solar power and battery storage] to be able to sustain themselves during problematic times – it’s a big deal,” said Tim McJunkin, a researcher at the Idaho National Laboratory, a United States government energy research lab.

He said the Adjuntas initiative was a “starting point” to scale up similar initiatives on the island, which the U.S. Department of Energy said in February would receive $1 billion to improve energy resilience among poor communities – including through solar microgrid projects.

The investment could also help Puerto Rico achieve climate change goals that include moving to 40% renewable energy by 2025 and 100% by 2050.

Rebuilding after Fiona

Extreme weather linked to climate change is giving impetus to efforts to develop alternative electricity sources fueled by renewable energy, particularly in remote and rural communities that are often worse affected by hurricanes and power outages.

U.S. Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm told Reuters last month that the transformation of Puerto Rico’s grid to solar and other renewables was “a question of life and death” after the long outages caused by Maria, and last year by Hurricane Fiona.

When the lights go out, solar panels backed up with battery storage can provide essential power to keep medicines refrigerated, ventilators running, and phones charged, potentially saving lives during hurricanes.

About a 30-minute drive from Adjuntas through Puerto Rico’s central mountain range lies the small, isolated town of Castaner, where another microgrid came to residents’ rescue when Fiona ripped through the island in September.

The storm caused an island-wide power outage, but batteries storing solar energy generated from about 120 rooftop solar panels in the town kicked in and provided electricity to five businesses including food shops and two homes.

“The system was put to the test. It was the only microgrid up and running before, during, and after Fiona,” said C.P. Smith, who heads the Hydroelectric Cooperative of the Mountain, the group that owns and operates the microgrid launched in 2021.

The cooperative is also working to develop the island’s first microgrid straddling different municipalities powered by both hydroelectric and solar energy.

High Costs

But hurdles remain for communities wanting to develop microgrids in Puerto Rico and other hurricane-prone parts of the Caribbean and Latin America – from high setup costs to challenges in accessing funding and technical expertise.

While the cost of solar panels has declined, battery storage is still expensive, said Cynthia Arellano, project manager at the Honnold Foundation, which donated about $2 million for the Adjuntas microgrid.

“We hope to be able to replicate this in the future at a lower cost,” said Ms. Arellano, an engineer who has been working on the Adjuntas project since 2019.

Besides the push for climate resilience, environmentalists and nonprofits in Latin America are backing renewable energy microgrids as a way for remote communities, including Indigenous Amazon rainforest groups, to become energy self-sufficient.

Successfully expanding such initiatives will depend on providing communities with the proper support and training, such as technical writing and fundraising skills and legal guidance, said Mr. Smith.

“We need to focus on capacity-building for low-income communities, paying and supporting leaders while they get these projects off the ground,” he said.

Training for the Castaner project included information on how to make solar panels more storm-resistant and how batteries work, said Carlos Alberto Velazquez, program director at the U.S. nonprofit Interstate Renewable Energy Council (IREC) office in Puerto Rico that has been supporting the cooperative.

Other challenges include energy sharing with other homes and grids, trading mechanisms, and cost efficiency, as well as constraints with solar power on cloudy days and the need to have maintenance and technical assistance to hand, Mr. Smith said.

“Moving to a PV [photovoltaic] microgrid needs to be a part of a solution but it cannot be all of the solution,” he said.

This story was reported by the Thomson Reuters Foundation.