In this museum, the path of human rights leads upward to light

Loading...

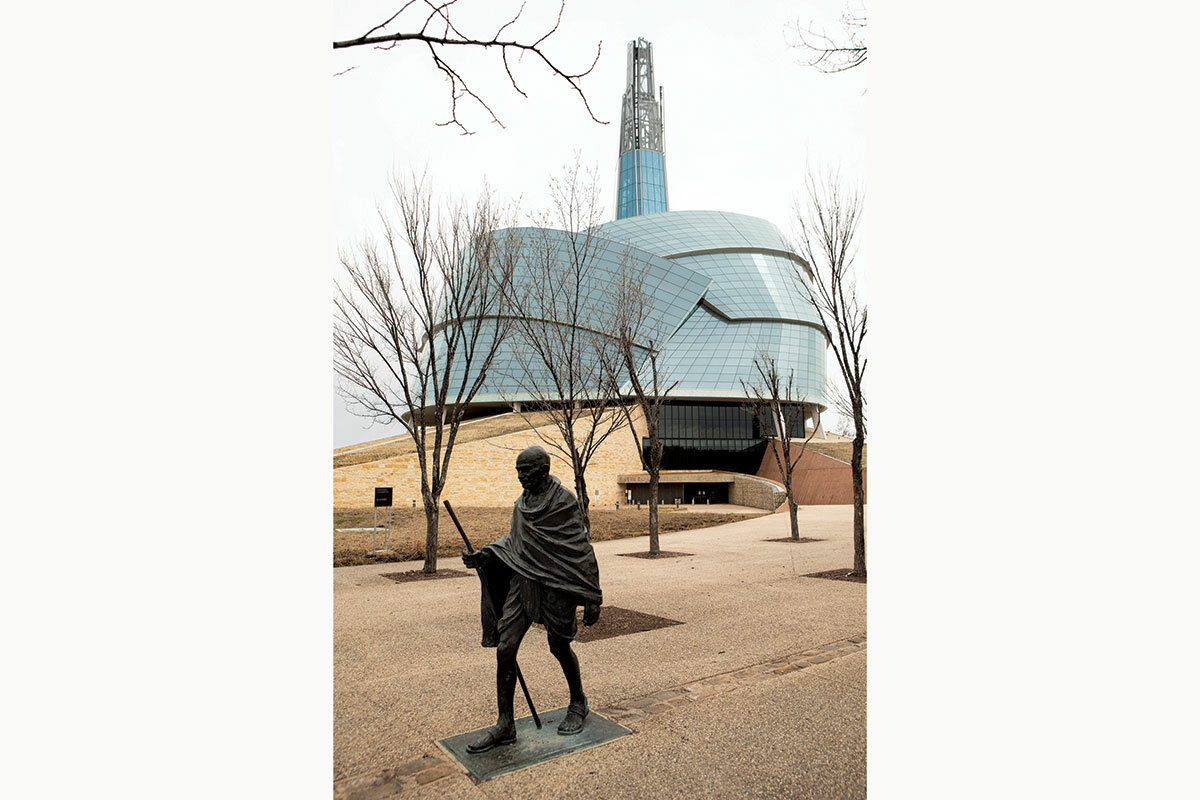

| Winnipeg, Manitoba

Set in the prairies, the Canadian Museum for Human Rights sits at the confluence of the Red and Assiniboine rivers in Winnipeg. Since its opening in September 2014, it has been billed as the only museum dedicated exclusively to human rights – past and present – around the world.

The museum takes visitors on a journey through the evolution of those rights. Starting at the dimly lit ground floor, visitors follow a timeline through key moments in history. As they ascend through the space, they witness the rise of democratic societies, the determination of prisoners of conscience, and the emergence of Indigenous rights. By the time the visit ends, guests find themselves in the 328-foot Israel Asper Tower of Hope, which offers a panoramic view of Winnipeg. Light from outside fills the space – a symbol of the museumgoer’s own enlightenment in understanding human rights.

A look at the news suggests that human rights are under threat in many parts of the world, including in the United States and Canada. The museum’s idealistic portrayal received a sharp reality check in 2020, when its management faced allegations of discrimination and harassment of Black, Indigenous, and LGBTQ staff at the height of the Black Lives Matter protests. This led to an external review, released that summer, which concluded that “racism is pervasive and systemic within the institution.” It’s not the first controversy the museum has faced. From its inception, it has been accused of propping up the myth that Canada is a benevolent leader in human rights on the world stage while the country has failed to address violations at home, from its treatment of Indigenous people to discrimination against Black Canadians.

The museum, which has worked to address the criticism, explores human rights issues at home with the exhibit “Canadian Journeys.” Among the Indigenous artists whose work graces the gallery is Jaime Black, whose “The REDress Project” installation reflects on the killing and disappearance of Indigenous women and girls.

Moving beyond Canada, the museum is responding to ongoing rights violations, from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine to the plight of refugees. At the end of May, it opened an exhibit called “Behind Racism: Challenging the Way We Think.” The exhibit is relevant not just to the challenges faced by the museum itself but also to the larger racial reckoning happening around the world.