Fearing authoritarianism, young Peruvians battle constitutional change

Loading...

| LIMA, Peru

On busy Jirón de la Unión in the Peruvian capital’s historic center, young fathers relent to children begging for electric-colored cotton candy, while couples wait in line for a just-from-the-fryer churro with arequipe, a liquidy caramel dear to Limeños.

Few of those strolling the tidy pedestrian street acknowledge a group of activists, mostly young people, arrayed in T-shirts emblazoned with “No to communism!” and holding aloft signs declaring “No to the constituent assembly.”

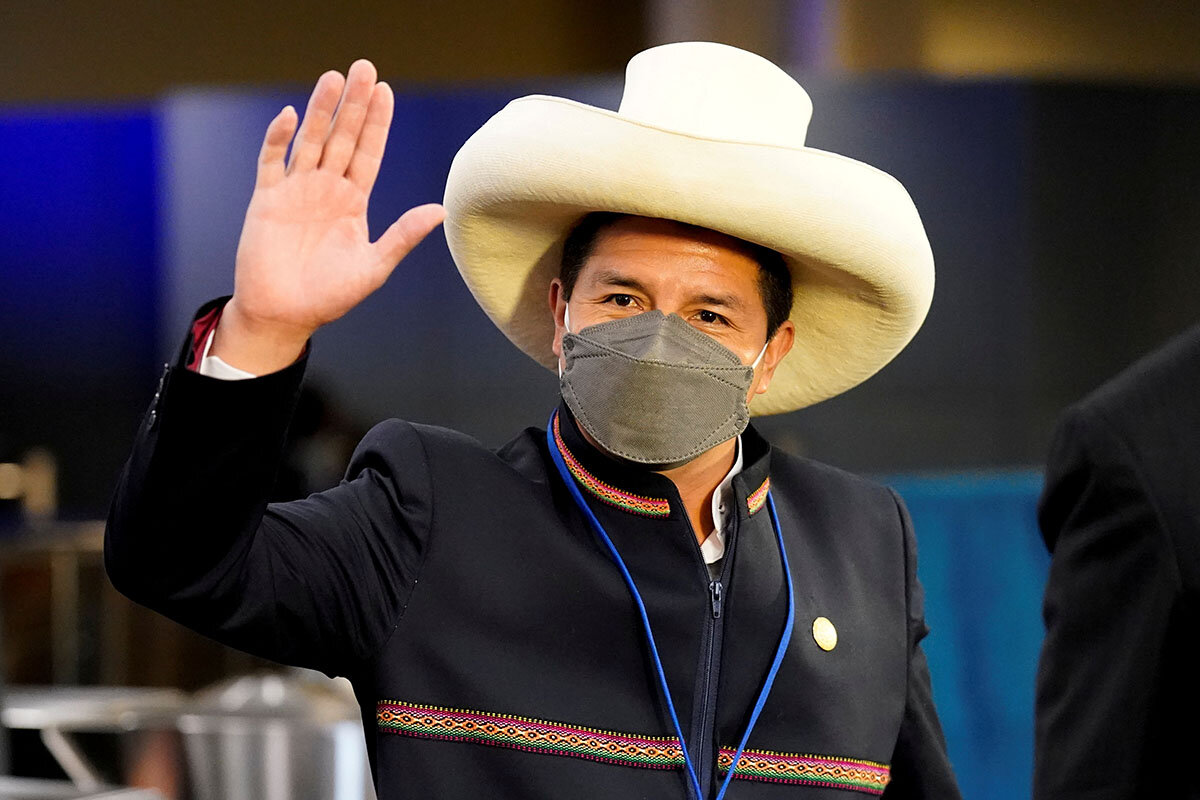

But occasionally a passerby stops to inquire about the group, and – if the activists can make their case – to sign a petition to stop Peru’s self-declared “Marxist-Leninist” president, Pedro Castillo, from succeeding in delivering a new constitution through a constituent assembly.

Why We Wrote This

Latin American populists have consolidated power at the expense of democracy. The region’s youths are now standing up to defend the democratic order.

A new charter was a campaign promise of Mr. Castillo, a former elementary school teacher. But after Mr. Castillo’s surprise victory in a bitterly won race in July, his critics worry he plans to lead Peru down the path of other Latin American countries where democracy has withered. From the late Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez and his successor Nicolás Maduro to Evo Morales in Bolivia and Daniel Ortega in Nicaragua, the region’s leftist populists have used constitutional reform and weak institutions to consolidate power.

Now a group of young Peruvians is determined to not let the same happen at home. In their fight, they join young counterparts across the continent who are leading political and social movements against the ruling classes to drive change.

In Argentina, armies of young women have mobilized to demand greater gender equality, last year succeeding in a hard-fought campaign to legalize abortion. In Chile in 2019, it was largely youths fed up with watching their country’s rising prosperity pass them by who filled the streets, brought Chile to a standstill, and won economic concessions and a process to deliver a replacement to the Pinochet dictatorship-era constitution.

And in Cuba, young people are at the forefront of an unprecedented protest movement pressing the government on deteriorating economic conditions and human rights abuses. Tensions were high in Havana Monday as authorities squelched a planned national day of protest, including with house arrests of dissidents.

“We don’t want our dear Peru to become another Venezuela,” says Armando Tapia, part of the small group seeking signatures on a recent Sunday afternoon. “Hugo Chávez stayed in power by rewriting the constitution first,” he says, “and our president wants to follow in those footsteps. We say no!”

“Slaughterhouse of democracy”

In some ways their “no” campaign is preemptive. President Castillo has only been in power for four months after eking out a victory with 20% of the first-round vote. Though he was backed by the Marxist Free Peru, he has since irked the party after replacing his far-left prime minister with a more moderate one who recently said constitutional reform is not a priority.

Still, Lucas Ghersi, the young constitutional lawyer leading the “no” campaign, says they can’t take any chances: Recent regional history shows that complacency is the authoritarian’s friend.

“We don’t want Peru to be the sheep that walks into the slaughterhouse of democracy,” he says. “We want to stand up while there is time and stop that from happening.”

Speaking in his office in a tony section of Lima, he is surrounded by stacks of some of the 1.3 million signatures his group has collected so far. He says he aims for an effort so overwhelming – collecting 3 million signatures in all – that it forces Congress to approve a national referendum on President Castillo’s constituent assembly plan.

The son of a high-profile Lima lawyer father and a media darling among the anti-Castillo press, Mr. Ghersi recognizes he is the son of privilege. Some critics insist his campaign is really about preserving the status quo, including Peru’s pro-market-economy constitution.

He maintains his campaign is not about class but about safeguarding the freedoms – including the freedom to improve oneself economically – of all Peruvians.

It was many of the poorest Peruvians who wanted this change in the first place. Peru’s constitution was written at the end of the rule of the country’s last dictator, Alberto Fujimori. Amendments over the years have resulted in a notoriously weak presidency, exacerbating Peruvian political instability. Over the span of one week last year, the country had three different presidents, a level of political turmoil that had demonstrators in the streets demanding a new constitution.

The case for change

The constitution does need refreshing, says Milagros Campos, a constitutional scholar at the Pontifical Catholic University of Peru, especially to forge a stronger presidency. But Mr. Castillo’s constitutional rewrite proposal today faces widespread opposition, with nearly 80% of Peruvians opposed to a complete overhaul.

Many of them simply distrust the president’s real motivations. Older Peruvians who lived through military dictatorship and the dark years of the Shining Path, the Marxist and Maoist-inspired group that waged a deadly guerrilla war in the 1980s and early 1990s, fear a return to their past.

For younger Peruvians who only know Shining Path and military dictatorship from history books, Mr. Ghersi adds, it’s the real-time experience of authoritarianism’s rise around the region that drives them. They’ve seen 1 million Venezuelan refugees arrive in Peru, according to the United Nations, many of them youths.

Institutional reform doesn’t figure on most Peruvians’ priority list either, says Professor Campos. “There are more poor Peruvians than a few years ago. People are worried about jobs and getting by,” she says. After a period of remarkable economic growth and rising prosperity, Peru was hit hard by the pandemic and growth crashed. “There’s a feeling that constitutional reform is not the change people need right now to improve their lives.”

An expert in Latin American constitutions, Professor Campos says the region’s many efforts at constitutional reform over recent years have largely fallen into two categories: political reforms, as in Bolivia and Ecuador, that have concentrated executive power; and the response to demands for economic and social reforms to dated constitutions, as in Chile and Colombia, that empower elites.

Peru’s case is more complex, she says, because it’s a mix of all these factors at once. In this context Professor Campos says the campaign against a constitutional assembly stands out as a “no” to any change – not the solution she believes Peru needs, or wants.

“The president’s idea of a new constitution is a little radical, and I understand the worries that it would open up the country to too many uncertainties or that the process to get to this new constitution would not be open to all Peruvians,” says Annie Mego, an occupational psychologist at an insurance company. “That doesn’t mean there should be no change,” she says, citing victims’ rights and stronger anti-corruption laws as her priorities.

Mr. Ghersi maintains that the campaign is not aimed at leaving Peru’s constitution untouched – for example he supports reforming the unicameral Congress to include a Senate.

But he says he first remains focused on the bigger goal of stopping Peru’s slide into authoritarian rule.

“I don’t speak for everyone supporting this campaign,” he says, “but what motivates me personally is the desire not to lose the dream and the promise that is Peru.”