One town’s beacon of 9/11 kindness: Gander shines on

Loading...

| Gander, Newfoundland

Charlotte Gushue was a Canadian third grader when four hijacked airplanes were used to perpetrate the deadliest foreign attack on U.S. soil. She hardly understood it. What she knew was that thousands of passengers, on flights suddenly barred from entering American airspace, landed in this small town in Newfoundland and that she was sent home from school.

A troublemaker back then by her own admission, she read the room and stayed quiet. When her mother, between hurried phone calls, asked her to go up and look through her books and stuffed animals to donate, she was mad.

Teeth gritted, she did it anyway.

Why We Wrote This

For all of the tragedy of 9/11 and all the repercussions the world still grapples with, one place has become a symbol of unabashed kindness. And it’s a story that shouldn’t be forgotten as the world finds itself emerging from the pandemic.

Like most children in Gander on 9/11, Charlotte got the rest of the week off from class, as schools immediately turned into shelters. But this was no snow day: Oz Fudge, who was on patrol as police constable, saw kids helping their parents drop off food, clean sheets, and toothbrushes, and some even cleaning toilet bowls.

“It just done the cockles of my heart,” he says.

Charlotte returned with her parents to her school and understood something major was happening: Sleeping on the gym floor were 770 passengers. Cellphones weren’t ubiquitous, and many of them had no idea what had happened until the community set up TV screens. Charlotte witnessed the horror on their faces as the images flickered.

“It’s a hard word to describe,” she takes a long pause. “There was something so big happening. ... And I don’t think my parents actually explained the concept of terrorism. I think the focus wasn’t on that for us, but it was really on what we can do and how we can help because that had to be a priority for everyone at that time.”

Over the next five days, she watched her mom tirelessly bake batches of tea buns and muffins, her parents doing their part to deliver food. She has no doubt that’s why she became a baker.

In a flour-dusted outfit in her sweet little “Cookie Starts With C” shop she just opened off the main stretch, Ms. Gushue also has no doubt that it set the tone for what she hopes the bakery will mean for the community. She’s cultivating the basic goodness Gander came to encapsulate on 9/11 – goodness that’s captured the world’s attention ever since.

“It was a very defining moment, even at age 8,” she says.

Gander may not look like much from the ground. The Trans-Canada Highway passes beside it, and motorists can get what they need without even turning into town.

From high in the sky it’s different: Planners built periphery streets in the shape of a goose head discernible from above. For Gander, it’s the airspace that matters, anyway: The airport – opened in 1938 – was a staging point for World War II Allies, and later, a refueling stop for transatlantic jets.

So, it was a logical landing point during 9/11: Gander received 38 commercial jets carrying about 6,500 passengers – half the number of the town’s entire population. Most in Gander and surrounding towns had a job they could do – taking people into their homes, offering hot showers or a quiet place to reflect, lending their cars, tracking down kosher food, helping to refill prescriptions, or taking care of pets that had been in cargo.

“We saw people from 95 countries that needed help. And we poured out love and compassion for complete strangers because that’s what we would want if we were stranded in their place,” says Claude Elliott, who was mayor at the time. “They couldn’t believe that complete strangers would bring them into their homes and say, ‘Hey, you know, just sit there. I’m going to work; you stay here for the day, take my car, go for a ride.’ They asked, ‘Is this real?’ But, you know, that’s the way we live here.”

Those actions, he says, were instinctive well before 9/11, on a rugged island where you stick together to survive. But since then, they’ve defined this town – inspiring the hit Broadway musical “Come From Away” – and have re-instilled simple lessons that 20 years later, and in the face of the pandemic, perhaps resonate even more now.

“When you look at it, you see two spectrums: What you saw was the worst of mankind in the United States [9/11 attacks] and you probably saw the best of it here,” says Mr. Elliott. “The more of that good news story we can get out, no matter what the story is, it’s good – get it out, because it seems harder to get the good out than the bad.”

Small offerings add up

For host and guest alike, the story doesn’t end on 9/11, but continues to reverberate. Kevin Tuerff, an American in Austin, Texas, was a passenger on his way back from Paris on 9/11 when his flight was diverted here. He still remembers the simplest gesture: a young boy handing him an air mattress, comfort from the cold floor.

“It’s a very humbling experience to be a recipient of kindness,” he says. It made such an impression that he started a “pay it forward” day at his company. Today it has grown into a “kindness” charity, Pay It Forward 9/11, that this year is focusing on random acts of kindness that forge unity – the kind the U.S. said it wouldn’t forget after 9/11 but so clearly has in its riven politics, says Mr. Tuerff.

That boy who gave him the mattress – which quickly deflated, but that’s beside the point, he says – would’ve been around Ms. Gushue’s age. It’s fitting – although coincidental – that when you walk into Cookie Starts With C, the first thing you see is a big bulletin board, with the words “Pay it Forward” painted in black cursive above it, where residents can buy treats for a stranger. One index card attached with a pushpin reads, “1 piece of Cheesecake. For: A police officer.” Another: “Muffin and Medium specialty tea or a coffee. To a mom who is just surviving.”

It sets the tone for the place Ms. Gushue wants her bakery to be – a tone that harks back to elementary school, she says: “With 9/11, my parents just brought sandwiches, books, muffins. Like, it doesn’t seem like a lot, but a simple offer of a hot shower or a comfortable bed can mean a lot. That all kind of funnels through my life. We can do a lot of small things and they add up to be really big things for a lot of people.”

Diane Davis was Ms. Gushue’s teacher on 9/11. She says this very lesson, which her former pupil is carrying forward, is one that she learned herself from 9/11.

The retired teacher has helped sponsor Syrian refugees in Gander. They often thank her with food. But sometimes they bring her gift cards for gasoline. “The first time it happened, I was upset, because they don’t make a lot of money. I’ve done it my whole life, said, ‘No, you don’t have to.’ But I realized that I take away their opportunity to get satisfaction from that,” she says. “So now I take it and say thank you.”

She tears up as she recounts the five days she spent helping to house, feed, and care for so many others. But she’s hardly the only one who feels 9/11 right at the surface.

A musical about 9/11?

“Come From Away” has added a whole new dimension to the Gander narrative.

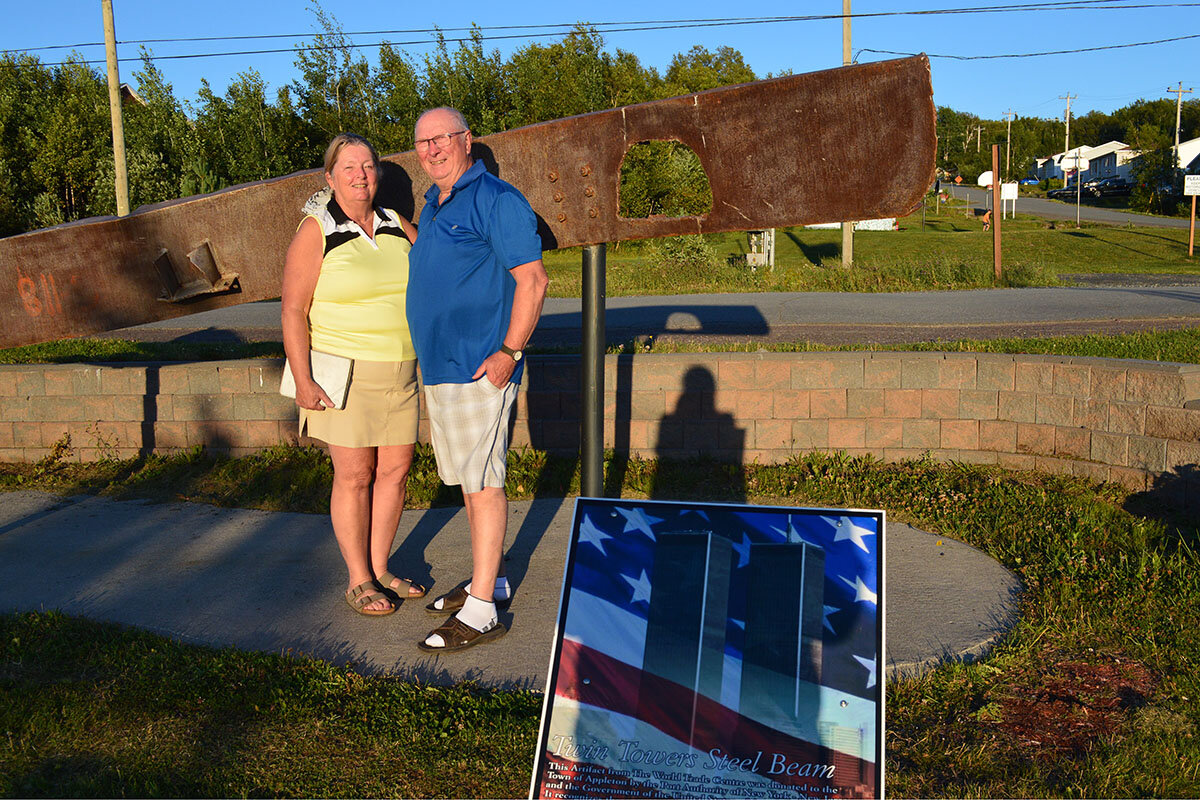

Derm Flynn – who at the time was the mayor of nearby Appleton and is portrayed in the musical as well as Ms. Davis, Mr. Elliott, and Mr. Fudge – says that when he heard a production was in the works, he had thoughts that “weren’t very nice, actually.” “We thought, ‘Well, how can you write a musical about 9/11?’ It’s almost sacrilegious. ... And also, ‘How can you write a musical about people giving someone a bowl of soup and a sandwich ... normal things that you would do anyhow?’”

Mr. Flynn explains that he was surprised by how wrong he was. His kitchen, where he was interviewed while cooking cod he’d just caught, is full of “Come From Away” memorabilia. The musical has kindled such fresh interest in Gander and surrounding towns that also welcomed passengers that he and his wife, Dianne, began offering tours of their home called “Meet the Flynns.”

The tour includes their story of the first night of the jet groundings here: The couple, now married more than 50 years, didn’t communicate that each separately had invited three people to stay with them, and the resulting collision of kindness had all six stranded passengers squeezed in on air mattresses and a chesterfield sofa. One of them became such a close family friend that the Flynns were the second people he called on the birth of his first child in New Jersey.

About 100 tourists have visited the Flynn home to revel in these tales.

What 9/11 summoned, COVID suppressed

A yearning for the Gander story is not surprising given the backdrop of something as unimaginable as 9/11, or given global pandemic repercussions today, says Jennifer Mascaro, lead scientist in the department of spiritual health at Emory University, in Atlanta.

“In dealing with trauma, both at the individual level and at the societal level, people try to make meaning and coherence that is positive in nature, soothing in nature, empowering in nature,” she says.

Gander Day, in August, was one of the first civic gatherings after Canada’s post-pandemic reopening. Mayor Percy Farwell welcomed back Gander citizens who’d gathered to listen to live music – much of it odes to tough island life. He said their actions on 9/11 were natural and that pandemic restrictions contradicted that basic nature: “When the best thing you can do for someone is stay away from them, that’s hard for us to get our heads around.”

Because of the pandemic, 9/11 anniversary commemorations – including a production of “Come From Away” – have been scaled back. But Mr. Fudge, now a Gander councilor, is sure it’ll happen next year: “[The story] reminds people that this is the way we should be living, where your neighbors worried about you. And I think people are looking for that something to hold onto, that light in the window, and they are saying, ‘I’d like to be able to get there.’”

He’s probably right: When “Come From Away” reopened in London in July, the cast had to hold for applause after the opening act for a minute.

“Usually, we hold for three to five seconds, and we are out,” says Petrina Bromley, a Broadway actor in the show who is from Newfoundland.

She expects the same reaction when the Broadway production is set to resume Sept. 21. “So many people have been through so much in the past year and a half,” she says.

“So, a little story about being nice to people goes a long way.”