Amid food pressures, Newfoundland sees a root cellar renaissance

Loading...

| Elliston, Newfoundland

When traveling through Elliston, a speck of a town perched off the Atlantic coast of Newfoundland’s Bonavista Peninsula, the sharp-eyed may notice five-foot-high structures scattered all over the town.

The bunker-like oddities are made of stacked flat stone, with small wooden doors offering a way inside. Tucked into the sides of grass-covered knobs or hidden in old potato fields, and with wisps of weeds and grass poking out from their facades, they seem to blend into their natural surroundings.

For years people had questions. “Are they bomb shelters?” they asked. Some wondered if anyone lived inside, or used to. “Are they from old Viking settlements?”

Why We Wrote This

In Newfoundland, an old-fashioned means of food preservation is finding new life amid pressures from climate change and the pandemic that have given a glimpse of threats to food security.

Actually they are Elliston’s root cellars: venerable food pantries that secured a source of food – carrots, parsnips, turnips, or beets – for Newfoundlanders as far back as 1839, even through the bleakest winters.

They may have been forgotten in history, with the advancement of refrigeration, global supply chains, and quick, on-demand food delivery. But their prominence in Elliston is a story of a town’s reinvention, and today they are far more than a quaint piece of cultural heritage. Root cellars epitomize the “grow local” movement, an ethos that has only deepened with pressures from climate change and a pandemic that have given the globe a glimpse of threats to food security.

“Root cellars almost fell into the backdrop,” says Troy Mitchell, a root cellar enthusiast and food security advocate in Newfoundland. “But growing up, the idea of having some control over your food was well known and just expected. I’ve noticed in the last year and a half, food security is something that people are latching onto.”

Sid Chaulk, the maintenance man for Tourism Elliston and local expert on root cellars, pulls out nails that he uses to latch a root cellar the tourism office uses (tourists sometimes leave it open, not realizing there are vegetables inside, he explains). “It’s dark and dingy, if you don’t mind coming in,” he tells me. “Keep your head down.”

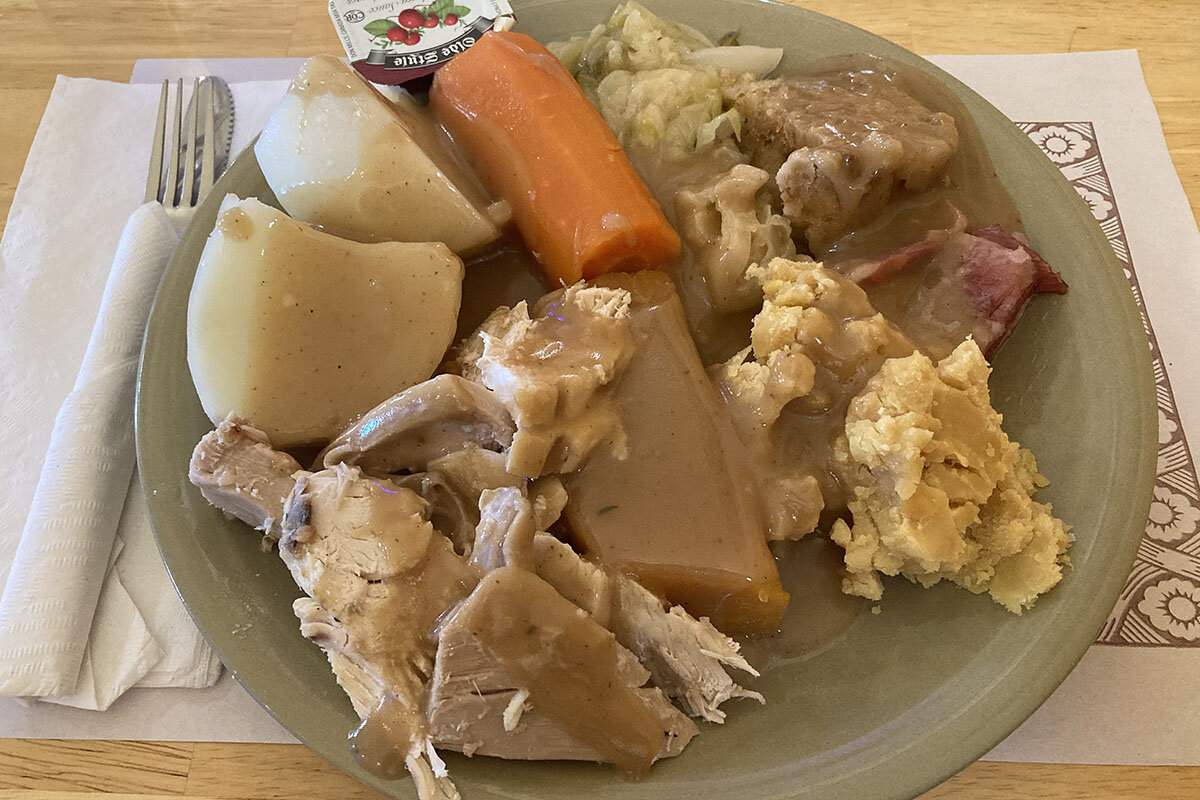

We head through one door, and then another, a double seal to keep the temperature at a constant 5 degrees Celsius (41 F) through blizzards or the odd heat wave. Inside, 60 pounds of turnips and 100 pounds of potatoes sit patiently in a wooden bin, waiting to be selected for the Jiggs’ dinner – a pile of bread pudding, pea mash, parsnip mash, salted beef, and boiled cabbage and carrot – served on Sundays at the adjacent Nanny’s Root Cellar Kitchen.

When Mr. Chaulk was growing up here, with six brothers and a sister, they relied on their root cellar. They had no refrigeration. His mom used the space to keep eggs, her pickled foods, and homemade jello too, which got them through springtime. Just as the structures inspire the imagination for unknowing visitors, they became fanciful worlds for kids, who sometimes teased a sibling by shutting him inside, even though they always got in trouble afterward.

He still grows potatoes; his son grows carrots and beets and stores them in his own root cellar. But most had gone into disuse, overgrown by fields and forests – until the 1990s. That’s when Elliston, like so many fishing communities, was decimated by the cod moratorium of 1992. Overnight, communities lost the only economic engine they had, the cod harvest. For a time the municipal tax base was so paltry that Elliston turned its lights off.

And then the city turned to tourism. Elliston boasts one of the world’s best land-based sites for viewing puffins, a seabird that has long drawn tourists. And many of the most prominent root cellars line the road leading to that colony. Elliston declared itself the “root cellar capital of the world,” and the town set out to restore 135 of them. Mr. Chaulk had a hand in the work on 23.

Mr. Mitchell, who is from Twillingate, northwest of Elliston, recently finished geo-mapping the root cellars that his late father-in-law began documenting in 2008 in that area. Theirs are a different design because of materials available, with an inner core of concrete topped by a mound of earth, and they found 232 – not that anyone is competing with Elliston, he assures me. “Elliston was the originator. Well before, they made root cellars cool again.”

They are perhaps at their “coolest” during the annual Roots, Rants and Roars festival, which demonstrates the grow-local ethos at its apogee. Held for two days in September in Elliston, it features “cod wars” between top Canadian chefs, ingredients gathered by local foragers, and of course root vegetables presented in any number of manners. Chris Sheppard, who has been co-running the festival since 2014, once designed a root cellar doughnut: carrot cake with parsnip cream cheese icing and fried beet chips on top.

For a second straight year, the festival has been re-imagined amid the pandemic. Visitors take a picnic basket prepared by participating chefs and do their own hike along the rugged coastline, with a Spotify playlist available of music by artists who have performed in the past. But Mr. Sheppard says the festival, one of Newfoundland and Labrador’s celebrated culinary events, has a deeper meaning, connecting the past to the present when it comes to self-reliance and food security.

“We went through a period of time in the beginning of the pandemic when grocery shelves were getting very bare because food couldn’t be brought over,” he says. “I hope we don’t forget what we’ve experienced over the last year and a half.”