As a Latin American populist shores up support, some see challenge for Biden

Loading...

| Mexico City

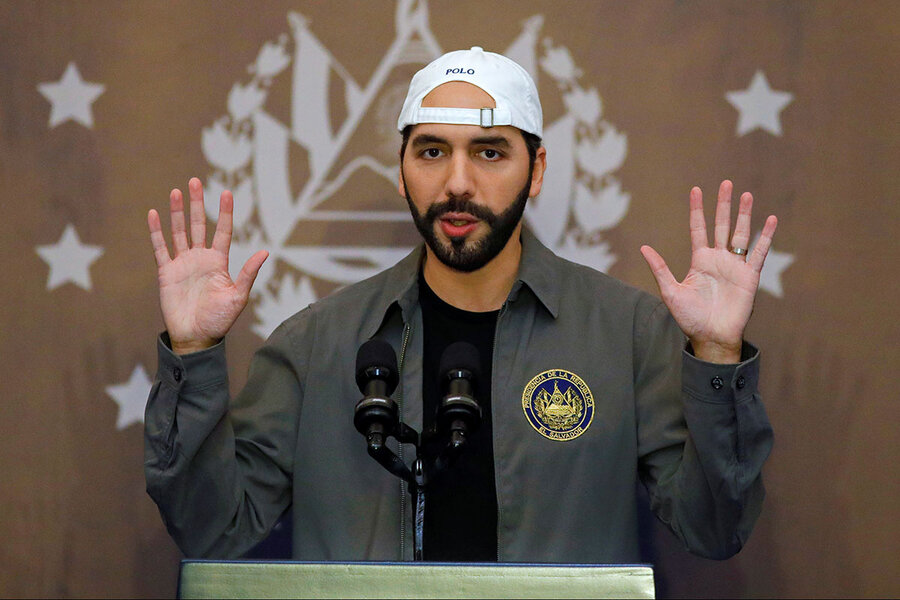

Salvadoran President Nayib Bukele won a decisive victory in last week’s elections – though his name wasn’t even on the ballot.

Strong support for his New Ideas party in the Feb. 28 midterms gives a seal of approval to his presidency. It allows the party to confirm Mr. Bukele’s nominees to key positions in the independent attorney general’s office and the Supreme Court. The party could also push for controversial moves like the removal of presidential term limits. By potentially gaining a supermajority via an alliance with a smaller party, New Ideas’ consolidation has raised concerns around the erosion of checks on presidential power, which has important implications for the United States, as well.

Under former President Donald Trump, the U.S. used development aid as an incentive for Central American governments to crack down on migration at all costs. In Mr. Bukele, the U.S. found a receptive partner. Now, the Biden administration is pivoting, saying it wants to help Central American governments strengthen democracy and fight corruption so as to tackle the root causes of migration.

Why We Wrote This

Can President Biden put democracy front and center in foreign policy? One test is close to home: a popular Salvadoran president who’s raising fears about democratic backsliding.

Mr. Bukele’s newly solidified power is not the first roadblock in the Biden administration’s efforts to pursue a values-based foreign policy: Myanmar, Saudi Arabia, and others have presented early tests. Arguably, President Joe Biden already had his work cut out for him in Central America, where some presidents hold onto power in highly contested, irregular votes, or barely go through the motions of fighting corruption.

El Salvador presents the unique challenge of a hugely popular president who is criticized by groups like Human Rights Watch over concerns that he’s put the country on the path toward dictatorship. Mr. Bukele has one of the highest approval ratings of any president in Latin America, with over 71% support; he’s also the youngest leader, at age 39.

“I wouldn’t be surprised if we witnessed a clash” between Presidents Bukele and Biden, says Carlos Mauricio Hernández, an expert in political science and philosophy at Universidad Centroamericana José Simeón Cañas in the capital, San Salvador. Mr. Biden will have to find delicate ways to “encourage [Mr. Bukele’s] respect for institutions and transparency without awakening his neurosis” of being under attack, Mr. Hernández says.

“That’s the big challenge for the U.S. right now,” Professor Hernández adds. “To relate with a leader who thinks and behaves more like a ‘Trump’ president,” who emphasizes personality and personal relationships, than a “Biden president,” who is more focused on institutions.

Some believe it’s too early to say how Mr. Bukele, who won the presidency in February 2019, will wield his enhanced power. “He might choose to respect the rules,” says Patricio Navia, an adjunct professor in the Center for Latin American and Caribbean Studies at New York University.

A populist rises

Mr. Bukele won office vowing to rescue El Salvador from widespread gang violence and systematic corruption perpetuated by both right- and left-wing governments. He’s leaned heavily on social media to get out his message – frequently criticizing or smearing those who contradict him. The president gained support at home during his quick and authoritative response to COVID-19, although public health experts deemed many measures counterproductive.

Until last week’s vote, El Salvador’s legislature was controlled by two traditional parties that constantly blocked Mr. Bukele’s agenda. “He didn’t have the tools or ability to negotiate with those parties, so there was a political standoff,” says Professor Navia.

That impasse led to controversial moves like Mr. Bukele deploying the military to the Legislative Assembly in February 2020 to pressure policymakers to approve an international loan.

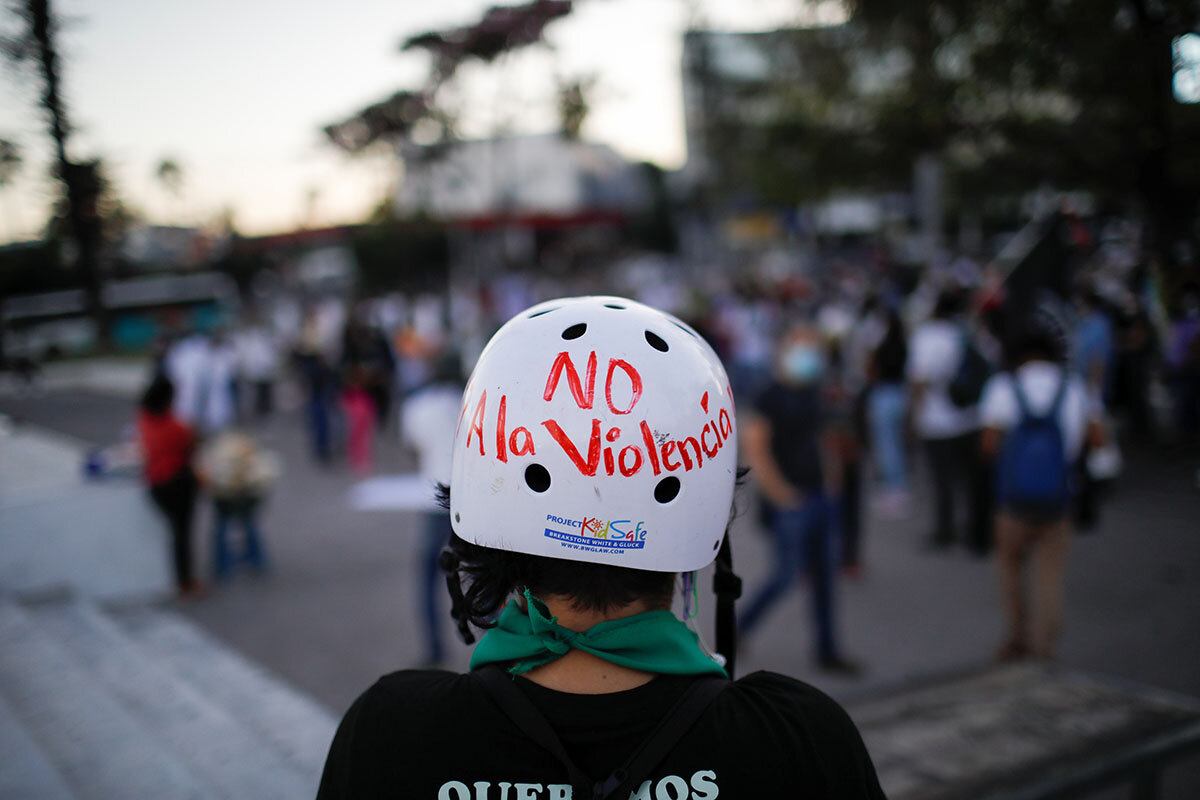

In a nation that suffered a long history of dictatorships and a 12-year civil war, public support for putting near-total power in the hands of a president is confounding to some.

But Jimmy Alvarado, a journalist at El Salvador’s leading independent news site, El Faro, says such support stems from a track record of corruption and perceived failures by elected leaders since the 1992 peace accords that ushered in democracy. He says he’s heard people refer to former dictators like Maximiliano Hernández Martínez in rosy terms, such as “there wasn’t any crime because he killed all the criminals.”

These comments underscore not only the serious impact violent crime has on so many communities in El Salvador today, but also the lack of faith in democracy to improve average citizens’ lives. “There’s not a lot of societal value placed on democracy,” Mr. Alvarado says, in part because “there hasn’t been much to illuminate the positive things democracy has brought” to the country.

Competing priorities?

A “significant challenge” for the Biden administration will be to accomplish all the things it wants to do in terms of addressing root causes of migration, “and at the same time keep democratic governance principles front and center,” says Cynthia Arnson, director of the Latin America Program at the Wilson Center.

“The region is more challenging than it was when [Mr. Biden] was first trying to put together a massive aid package to address root causes of migration” as vice president under Barack Obama, she says, citing increased levels of government corruption and organized crime.

Mr. Biden’s plans for the region have been touted in general terms, but not announced in detail.

Will he be “more concerned with promoting democracy, or stopping a migration crisis?” Professor Navia asks. “Obviously [Mr. Bukele’s victory] doesn’t help with the idea of promoting democracy, but it might make a migration crisis less likely now that there is somebody in charge in El Salvador.” This contrasts with the legislative impasse during Mr. Bukele’s first two years and may help bilateral negotiations since Mr. Bukele now has a stronger mandate.

Analysts agree there are concrete steps Mr. Biden can take to start building stronger relations with El Salvador and to prioritize the importance of democracy. For starters: naming a U.S. diplomat to replace a Trump appointee who left in January.

There’s also the need to tread lightly, engaging Mr. Bukele without criticizing him. “The U.S. should support policies popular among Salvadorans. That way Bukele will have more incentive to support those policies as well,” says Mr. Navia, pointing to anti-corruption measures as an example.

“The U.S. shouldn’t make the same mistake with Bukele that it made when [Venezuela’s Hugo] Chávez first came to power, popular and democratically elected. The U.S. can’t declare him a dictator after overwhelmingly winning free and fair elections. That would be the worst possible strategy.”