In Venezuela's reaction to US sanctions, a possible 'Russia factor'

Loading...

| Mexico City

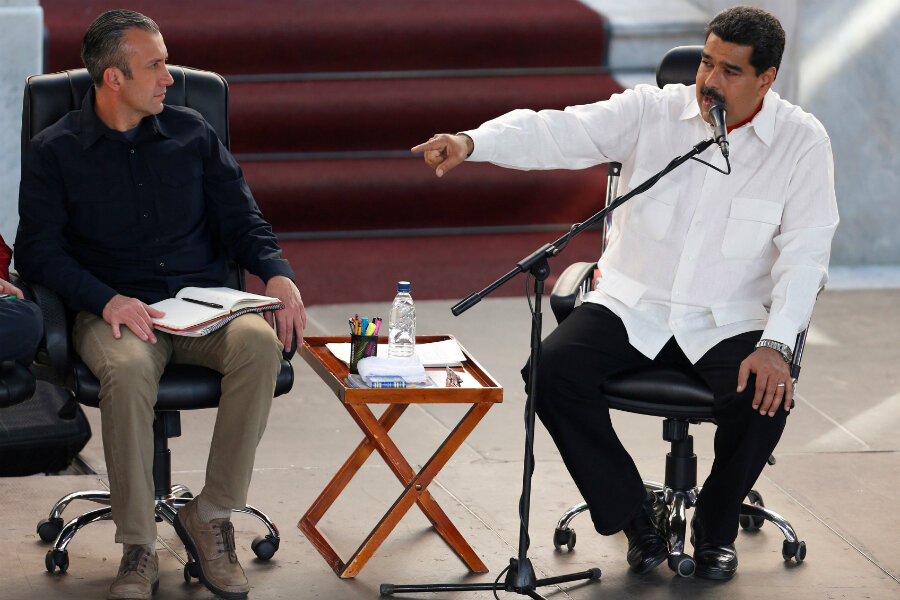

When the United States announced sanctions against Venezuelan Vice President Tareck El Aissami Monday, many prepared themselves for a “déjà vu” moment.

For nearly two decades, such US actions have served as an opportunity for populist politicians to rally support against US meddling.

Former President Hugo Chávez, who died in 2013, was a master at calling out “imperialist” Washington. And after the Obama administration slapped sanctions on seven Venezuelan leaders in 2015, many neighboring countries told the US that its involvement might hurt more than help any efforts to resolve Venezuela’s economic and political crises.

In some ways, Venezuela's current administration delivered as expected this week, after the US Treasury charged that Mr. El Aissami oversaw ships and planes transporting thousands of kilograms of cocaine, and worked to protect drug lords. El Aissami referred to the “miserable and infamous aggression” of the US and said that by singling him out, the US was simply recognizing his status as an anti-imperialist revolutionary.

But President Nicolas Maduro, at time of publication, has been uncharacteristically quiet, posting nothing on Twitter and leaving it to other officials to condemn the US. And no one, so far, has mentioned President Trump by name.

The change in tactic, some analysts say, comes down to a third-party player: Russia, which is a friend of Venezuela.

In the lead-up to President Trump’s inauguration, there were reports that Mr. Maduro was holding out hope that the new US leader could serve as an ally for Venezuela. “There was a lot of anticipation for a hands-off policy from Trump,” says David Smilde, a senior fellow and Venezuela expert at the Washington Office on Latin America.

“Today’s hesitation from the top” is explained by a desire to stay tight with Putin and hold out hope for future cooperation from Trump, given the signals that US-Russian relations could improve under his administration.

“This is what in international theory would be a ‘friend of my friend is my friend’ relationship,” Mr. Smilde says. “What Venezuela has been hoping is that the friendship between Trump and Putin will bring them into the triangle, and there will be a friendship between Trump and Maduro.”

Russian investments

The sanctions, which include freezing El Aissami's assets in the US and barring him from any financial dealings with Americans, “complicate foreign relations” for Venezuela, adds Dmitris Pantoulas, a Caracas-based political analyst. Maduro may feel forced to be more prudent in his response to the US because he doesn't want to risk damaging Venezuela's partnership with Russia, Mr. Pantoulas says. The Kremlin has sold Caracas some $4 billion in arms since 2005, according to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. Russia has also invested billions in Venezuela, and the two countries have shared interests in oil.

In leveling its sanctions, the Trump administration may have been playing more to domestic interests than international ones. Some 34 senators have been pushing for hard-line measures like this against Venezuela, sending Trump a letter last week urging him to step up the pressure on Venezuela.

“It’s not a particularly impactful measure, except that it could ironically reinforce unity among government officials in Venezuela … and be counter-productive to US preferences,” says Eric Hershberg, the director of the Center for Latin American and Latino Studies at American University in Washington.

Venezuela has been suffering dual political and economic crises the past several years. Food and medical shortages are sweeping the country, Maduro’s approval ratings have dropped below 20 percent, and the government is moving decidedly away from democracy toward dictatorship, Mr. Hershberg says. Last month, Maduro granted El Aissami powers typically reserved for the president, which make this week’s sanctions particularly worrisome.

“These sanctions are really bad news,” says Smilde. “We have a vice president who is more powerful than any before,” and now that he has been labeled a drug “kingpin” by the US, there’s concern that if the opposition came into power during the next presidential election, he could be extradited to the US, Smilde says.

“There’s now a clear motivation to make sure there is no democratic transition of power.”