Lucha Libro: Peruvian writers 'duke it out' for a book contract in masked competitions

Loading...

| Lima, Peru

On a recent weeknight, a tall, masked man going by the pseudonym “Joto” sat in a cramped backstage room, along with seven other people in their 20s. Some were nervous; others appeared composed. Every one of them wore a Mexican wrestling mask. But instead of wrestling, they were there to write.

“The mask gives you a sense of security. When you know nobody’s going to recognize you, it makes writing easier,” says Joto.

This was one night in a series of popular literary “matches” known in Lima as Lucha Libro – a play on the popular Mexican wrestling event known as Lucha Libre. In the Peruvian version, instead of headlocks and body slams, aspiring writers compete against each other by writing short stories in front of a live audience, all for a shot at the grand prize of a publishing contract.

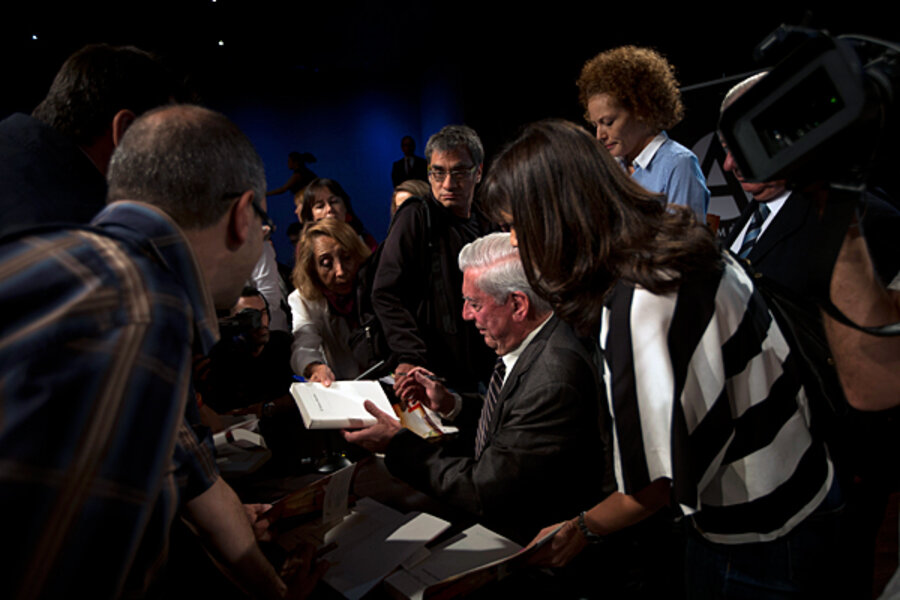

Peru is the birthplace of writers like Mario Vargas Llosa, and poet Cesar Vallejo. Yet today books are prohibitively expensive, often costing twenty or thirty dollars for a paperback. As a result, readership is low, and publishing contracts are even harder to come by than in the US. Nonetheless, the Andean country has plenty of aspiring writers, eager for a big break.

“Lima is still dominated by last names, and social circles,” says Christopher Vásquez, the writer who runs Lucha Libro along with his wife, event producer Angie Silva. “This [event] is democratic, because here you come together in front of a public made up of readers, and no one knows who’s behind the mask.”

The concept is simple: Each writer gets three words they have to incorporate into their story, a laptop connected to a large screen, and five minutes. Their writing – including errors, deletions, and deadends – is projected in real time before a packed room. At the end of each round, the judges pick a winner.

On the night that Joto participated, it was standing room only. A man in a striped referee’s shirt announced contestants. A DJ played music, and during breaks a young woman in shorts and high heels walked across the stage with a card announcing the next round. When it was Joto’s turn, he typed out a grisly short story about infanticide. Other stories included single motherhood, flamenco dancers, and a man who kills his mother-in-law.

'An investment'

After a series of crises starting in the seventies – first, a military government, then a civil war, and then the collapse of the economy – Peru is more stable than it was a few decades ago, and the economy is thriving. But Jaime Cabrera, a book critic and author of the popular blog Lee por gusto (Read for Pleasure), says that the government still isn’t prioritizing literature – and even now that they have more money, neither are most consumers.

“Culture is an investment. Before [if people had money] they’d splurge on a book. Now, they splurge on clothes, or electronics,” says Mr. Cabrera, who has also been a judge at Lucha Libro.

Cabrera also pointed to a 2009 study of reading comprehension among school children done by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), which found Peru to be ranked 62nd of 65 countries. He says Peru desperately needs initiatives that encourage both writing and reading, and applauds independent efforts like Lucha Libro.

A half hour before doors opened for the Lucha Libro event, a line had formed outside the venue, and it snaked around the block. People in their twenties and thirties came straight from work to stand in the cold, waiting for a chance to watch.

Vanessa Vásquez was one of them. Like many attendees, she says she’s also an aspiring writer, and was even a contestant last year. Ms. Vásquez sells some of her stories abroad, but says there’s not much of a domestic market for her writing. She works in advertising to pay the bills. But she adds, the environment for writers is improving in Peru, thanks to events like Lucha Libro.

“You might come just to hang out and have fun, but you still end up reading what people are writing. You start to realize that you’re living in a place where you’re surrounded by talented people. And this is where they get a chance to push themselves, and show off their work.”