El Salvador: buried treasure or fool's gold?

Loading...

| San Isidro, El Salvador

Walking through a sea of businessmen and information booths at a Toronto trade show, mining executive Tom Shrake saw gold.

The poster board that caught the eye of Mr. Shrake, president of Canada-based Pacific Rim, detailed core samples from a deposit in northern El Salvador – fittingly called El Dorado, or the golden one. It's a name that conjures up images of fabled lands brimming with riches that have lured European explorers to Latin America for centuries.

By Shrake's calculations, the geologist's company should have sampled deeper into the earth. "My gut, my geologic gut tells me there are over 5 million ounces [of gold] there," says Shrake, who immediately booked a flight to El Salvador to take a look for himself. He paced the property, gauging surface-level geologic formations that might give an indication of what lay thousands of feet beneath him. "By the second day, I was ready to acquire the district."

But in the 11 years since Pacific Rim first started exploration in El Salvador, the riches of El Dorado have remained as elusive as the legends imply.

Pacific Rim has yet to build its mine. Instead, it has filed a costly international investment dispute against the country to recoup lost investment and future lost profits for what it claims was the forced expropriation of its property. Nationwide protests, calls to ban mining, and even the death of some activists have served as a grim backdrop.

Over the past decade, mining has boomed around the world. Investments in Latin America's mineral industry are projected to be $327 billion between 2011 and 2020, according to Chile's Centre for Copper and Mining Studies. As many as 1,500 Canadian-owned mines were under development in Latin America between 2000 and 2010, and China, long involved in extraction industries in Africa, is now the third largest foreign investor in the region. Though the industry can bring development and higher tax revenue, it can also spur cultural, environmental, and legal clashes.

In the high-risk, high-reward world of mining, Pacific Rim is a small player, but one that, like many others, saw new opportunity as gold prices rose. As a result, its case has created a closely watched face-off between two powerful entities, both interested in investment and jobs, but at odds over the best means to that end. And the role of investment dispute tribunals, which exist to provide a nonpolitical venue to resolve disputes without slow and costly litigation, has come into question – with some arguing that a tool aimed at ensuring fair treatment of investors can in fact rein in host nations' abilities to reevaluate policies and laws in the name of human rights or democracy.

'It's complicated'

The province of Cabañas is a bumpy 90-minute drive northeast from the capital, San Salvador. In August, at the height of the rainy season, vibrant lime-colored grass grows tall along the edge of the road, shades of dark olive punctuate the leaves that weigh heavy on amate trees, and yellow-green cornstalks grow inconceivably along steep ridges and cliffs.

It's here that Pacific Rim explored for gold between 2002 and 2008. Cabañas is one of the poorest provinces in El Salvador and has seen an increase in gang-related crime in recent years. It was also hit hard by the country's 12-year civil war, which ended in 1992 with a peace accord between the government and leftist guerrillas.

In the years after the war, El Salvador focused on economic liberalization, signing on to international trade treaties like the Central American Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA), creating an investment law to reassure international businesses, privatizing banks and electricity, and creating a US-dollar based economy.

In 1996, it modernized its mining law, drawing new bids to explore – and ultimately, sparking a showdown in Cabañas that spread nationally.

Dionisio Galindo sits with his shirt slung over his shoulder by a dirt road in El Llano, Cabañas, playing cards with a group of men. It's 10 a.m. on a Tuesday, but no one is at work: Other than growing corn and beans in the fields, there are few opportunities, Mr. Galindo says.

"Why doesn't the government make more jobs? That's the problem," says Galindo, who worked for a Pacific Rim subcontractor.

An estimated 43 percent of the country is underemployed, and some 20 percent of gross domestic product is made up of remittances sent from families and friends abroad. Galindo says having a job and then losing it was tough for him and others. But does he want the mine to open?

"It's complicated," he says. Like many here, he expresses a fear of the unknown – damage to land, water, and potentially, people's health.

Ultimately his answer is yes: He'd work for the mine "because I need work, but I'd do it knowing there'd be consequences tomorrow," he says, citing deforestation and water contamination already present from other industries.

'Welcomed with open arms?'

The manufacturing boom that catapulted Asian economies over the past decade largely bypassed Latin America. But economic growth elsewhere fueled demand for the region's vast deposits of oil, gold, and copper – and the prices for these commodities shot up. Gold prices grew from about $340 an ounce in 2003 to $1,900 an ounce in 2011, and investment in the extractive sector increased globally as well.

But with that increase came trouble. Latin America has been host to myriad mining-related conflicts, with protests and violence grabbing headlines from Mexico to Peru to Chile.

"The benefits [of mining] in terms of taxes go nationally, but the social and environmental problems stay here," says José Ignacio Bautista, mayor of San Isidro, just minutes from Pacific Rim's administrative offices.

"According to the mining industry, the best thing that could happen to a country is a mine comes to town. And yet mining companies aren't welcomed with open arms," says Graham Davis, a professor of economics and business at The Colorado School of Mines.

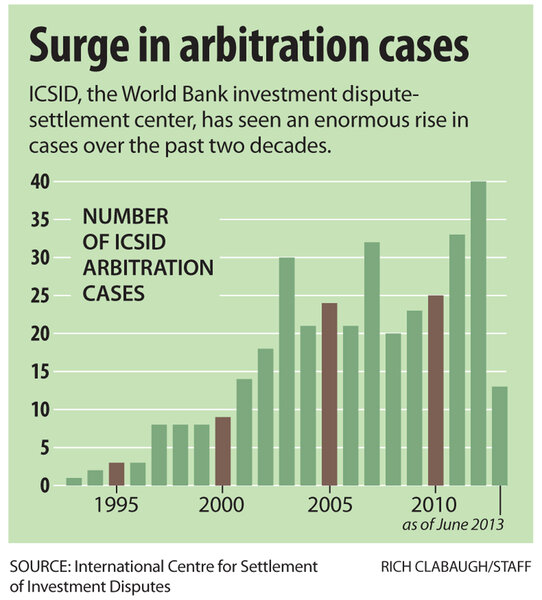

About 15 years ago the industry started to ask itself why that was, Mr. Davis says. Since then, there has been a push for universal standards, and groups like the International Council on Mining and Metals were formed to help regulate the industry. But the rise in international investment continued to drive more disputes, and a surge in arbitration.

Over the past 15 years, "a number of things coincided" to cause the increase in arbitration, says Louis Wells, a professor emeritus of international management at Harvard Business School. In addition to commodity prices, there were resource nationalizations and financial crises in Argentina and numerous Asian countries that "generated substantial disputes."

Law firms began creating specialty groups, which also amplified arbitrations. "The firms now had the expertise to tell a company 'you've got a claim,' " Mr. Wells says.

In 2000, just three cases came before the World Bank's International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID) related to extractive industries such as oil, gas, and mining, according to the Institute for Policy Studies. The two decades preceding saw just seven such cases. But by March 2013, the number of such cases pending had jumped to 60 at ICSID. That made up nearly 36 percent of all pending cases, reports IPS.

"From the data I've seen – at a national level – mining activity benefits a country more" than had it not had extractive activity, Davis says.

But in Cabañas, Mr. Bautista says he expects prostitution and crime would increase if a mine opened. It's a matter of having the right government controls in place to make sure the benefits of mining outweigh the risks, he says.

"What's worse is to die of hunger sitting on top of such an opportunity," Bautista says.

An organized opposition

When Pacific Rim arrived, it brought "a more visible face" to mining, says Bautista. From building walls around a school to donating jerseys to sports teams to offering adult literacy courses, giving back was a key tenet. "We really benefited from the social work," the mayor says.

Pacific Rim, however, was also drilling more than 670 holes – up to 2,300 feet in length, across a 34-square-mile exploration zone.

The results of that drilling lie stacked in long, rectangular boxes packed into six large shelters behind Pacific Rim's offices. The samples look like giant pieces of sidewalk chalk in shades of gray and brown.

It wasn't long before stories about the effects of drilling started drifting through the department. The company says it received four complaints from local mayors: two about wells drying up, and two about cattle that died after construction-related accidents. Bill Gehlen, vice president of exploration, says the issues were resolved.

But some nongovernmental organizations and community members claim there were more problems. Property was reportedly damaged, such as fences cut by drill teams and geologists. José María Velasco in the village of Trinidad says he came across a barrel of water used during the drilling process that had turned white and had dead frogs floating in it. The stories made some people feel disrespected; others, scared.

Antonio Pacheco is executive director of the Association for Economic and Social Development (ADES), an NGO founded in Cabañas to support sustainable development and social action. "I thought [a mine] would solve employment problems and help the community overcome poverty," Mr. Pacheco says. "That was the concept the people had and the idea ADES had," he says.

But mining wasn't something he'd ever dealt with. He directed local concerns about water and livestock to authorities, he says. "But there was a moment when people came back and said, 'Look, we've been to all the offices, but no one is paying attention to us.' "

ADES was stymied, Pacheco says. "We didn't have the research or the staff to tackle such a complex issue … but the insistence of the people made it clear they needed our help."

Pacheco reached out to other nonprofits at home and in neighboring nations. In 2004, he helped organize a mining forum to discuss what the industry could mean for El Salvador.

In February of that year, Pacific Rim held 10 public consultations in Cabañas. About 200 people were at each meeting, says Betty Garcia, who spearheaded the company's public outreach. There were 550 home visits and meetings with local leaders as well, says Ms. Garcia.

In September, the firm presented a tweaked mine design that took into consideration local concerns about water. "We're really proud of the environmental design," says Shrake, citing a rainwater catchment system and measures against chemical leaks. "We went the extra mile."

The company submitted its environmental impact study to the Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources (MARN) at the end of 2004, and everything appeared on track, says Shrake.

But support was growing nationally for ADES's movement, which, after commissioning a technical evaluation of the mine plans by North American geologist Robert Moran, had become decidedly antimining. By 2005, with the support of Oxfam International, ADES formed The National Roundtable Against Metallic Mining (The Mesa) with 12 other NGOs. In 2006, they submitted a bill to ban all mining.

"We have the unique opportunity to be the only country in the world with mineral resources that chooses not to mine," prioritizing life and the environment, says Alejandro Labrador, The Mesa's communications manager. By 2007, the movement had the support of the politically powerful Roman Catholic Church (read more about the Catholic Church's role in the mining issue in El Salvador).

Shrake, "a child of the '60s," says everyone has the right to protest, but he believes the opposition's arguments are "based on science fiction" and that they're "well financed" by anticapitalist and antimining groups.

But El Salvador has an “incredible history of protest" and raising awareness of citizen rights, says Ellen Moodie, associate professor of anthropology and Latin American studies at the University of Illinois at Urbana – Champaign, who has studied political expression and social movements in El Salvador.

"For 10 years the company didn't have any opposition, no organized opponent," Pacheco, from ADES, says. "We mobilized at the community's request."

The movement's tactics have been criticized: Fliers circulated at one point saying "Death to Canadian Miners," and Pacific Rim documented harassment, including an incident in which guns were drawn. Mr. Labrador says The Mesa does not condone violence.

Meanwhile, many Salvadorans say they were offended when the company launched an aggressive "green mining" advertising campaign.

The ads implied that those who were antimining "were ignorant or against development," says José María Tojeira, former rector of the University of Central America (UCA). "The ads provoked a more combative reaction."

Navigating public opinion

As the opposition movement grew nationally, the government was in the process of reviewing Pacific Rim's application for extraction. In the end, the company was neither granted nor denied a permit to build its mine – a limbo Pacific Rim blames on corruption. Shrake says he doesn't believe the opposition has anything to do with why his company is permitless.

But others were chiming in as well. The ombudsman office for human rights was sharing its concerns with government ministries. Yanira Cortez Estévez, the ombudsman for Environmental Defense, says she immediately "asked [the ministry] to respect the opinion of the population" worried about mining, after seeing water contamination near a former mine in the eastern province of La Unión. The water there was rendered undrinkable because of acid drainage – a naturally occurring process that can be accelerated by activities like mining.

Evaluating the risks of mining and the validity of complaints was a challenge for MARN. No one on staff had the necessary technical knowledge, says Salvador Nieto, the ministry's legal adviser and chief of affairs – a result of El Salvador's scant experience with mining.

In May 2007, the Economic and Environmental Ministries announced they would put all permitting on hold until a strategic study on metallic mining in the country was completed.

Measuring the public's stance on the issue was a growing challenge as the topic became more and more politicized. In the lead-up to presidential elections, then-President Tony Saca and eventual victor Mauricio Funes both came out against mining. According to a poll commissioned by Pacific Rim in 2008, 2 out of 3 Salvadorans said they would support a mining project here. But the NIMBY factor kicked in: A survey by the UCA found 63.8 percent of people polled disagreed with the statement, "There should be more mining projects opened in my municipality."

In Cabañas, the issue unearthed existing tensions between the largely conservative population and smaller leftist communities. Local journalists received death threats for their antimining coverage. Three environmental activists were killed, along with one of their children. It was determined two of the three were murdered because of longstanding family disputes that were exacerbated – or taken advantage of – by the arrival of mining activity, according to WikiLeaks documents from the US embassy and local accounts. The police never determined a motive for the torture and death of the third activist.

The government's strategic study concluded in 2011 that mining could be feasible here if appropriate regulations and safeguards are put in place. Representatives from MARN and the Ministry of Economy (MINEC) say steps, including international trainings of ministry staff, are under way. "We have to take into consideration the environmental and social concerns of this kind of development," says Ricardo Salazar, MINEC's director of hydrocarbons and mines.

'Rules of the game'

Pacific Rim first filed a $77 million arbitration with ICSID under both CAFTA and El Salvador's national investment law for what it said was the government "changing the rules of the game" laid out in its mining law. The government simply stopped communicating with Pacific Rim, says Mr. Gehlen. (Benjamin Pleités Mazzini from the attorney general's office says by law this is considered a technical 'no.' If Pacific Rim wanted to contest that, they should have filed a case in local courts, he says.)

The ICSID case was heard under CAFTA and dismissed during the jurisdiction phase. It is now being heard under El Salvador's investment law, and Pacific Rim has upped the price tag to more than $300 million.

Pacific Rim sold other properties to maintain El Dorado and its "investors have already lost half of their investment," Shrake says. "If we get this permit, the suit is gone," says Gehlen.

Arbitration is increasingly used by investors in a way that goes beyond its original intent, says Noel Maurer, associate professor at Harvard Business School. "Fidel Castro is who people were thinking about when writing the underlying rules," he says. "They weren't thinking a change in tax law … or steps [to] address environmental changes."

When Uruguay heightened warnings on tobacco products, including putting graphic photos on cigarette packages, for example, PhilipMorris took the case to ICSID. When post-apartheid South Africa's Constitution added the goal of redressing inequalities, a group of investors said bringing in historically disadvantaged groups as mine shareholders was unlawful expropriation.

The tribunals exist because "investors don't trust courts in the host country, and the host country doesn't trust courts in the [investor's] home country," Wells of Harvard says.

Susan Karamanian, an associate dean of international law at George Washington University, says the process of investment dispute resolution isn’t going away. And because of this, space is slowly opening up for changes, among them, greater transparency. In 2006 ICSID allowed parties not directly part of cases to offer information or perspective, and this case was partially webcast.

The future of mining

The arbitration process has left few players here content. The government says it won't consider removing itself from the ICSID Convention, as Venezuela and Bolivia have. But Brazil, for example, has maintained high levels of investment without allowing access to arbitration.

Last month, El Salvador's investment law changed. If a company isn't protected under a bilateral investment treaty that allows for dispute resolution, its claim will be heard in local Salvadoran courts, says Daniel Rios Pineda, MINEC's legal consultant.

The rolling boil of opposition marches in San Salvador and confrontations in Cabañas have reduced to a simmer, though demonstrations still take place, and The Mesa continues to advocate for a law banning mining.

Hundreds of people descended on San Salvador’s iconic Savior of the World statue in August to march for the passing of a national water law. Many in the sea of demonstrators were also there to protest mining, including two busloads of people from Cabañas and the entire staff of ADES. “My water – this country’s water – is already contaminated. And mining will make it worse,” says 70-year-old María Alejandro Ramos, wearing a yellow headband that reads “No to mining!”

Back in Cabañas, Concepción Rivas Reyes sits on the San Isidro town square repairing a chair. He remembers his "hard and dangerous work" in a mine near the El Dorado site more than 60 years ago. The company brought electricity to town and built a graveyard.

His daughter stands nearby. "He speaks so highly of mining," says Janet Flamenco. "If it was OK when he worked there, I think it'd be OK today. There's better technology, right?"

But, she says, "Ultimately, who can know?"

• Reporting in El Salvador was made possible by a fellowship from The International Center for Journalists.