Putting a price tag on violence against women in Latin America

Loading...

| Mexico City

Authorities have opened all-women’s police stations in Brazil for victims of domestic violence to seek help. NGOs have produced soap operas in Nicaragua to teach young men to live violence-free lives. In El Salvador, a women’s group painted proclamations on the facades of homes in Suchitoto declaring them “free of violence against women,” as a zero-tolerance, public pressure campaign.

But now a first-of-its-kind study is underway that could have the greatest public policy implications: quantifying the intergenerational price tag of domestic violence.

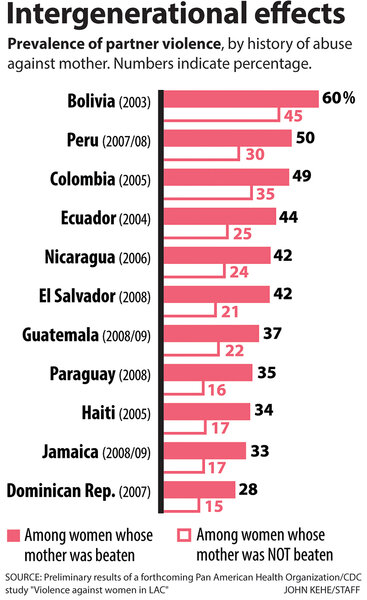

Previous studies have looked at the cost of lost productivity of women who are victims of violence in various countries in the region – finding losses of anywhere between 1.6 to 4 percent GDP. But this new study, called “Causal Estimates of the Intangible Costs of Violence Against Women in Latin America and the Caribbean," aims to look at the future losses associated with their children.

“This is the first time that a study tries to [look at] the costs of the next generation. That is what is really new,” says Gabriela Vega, a leading specialist in domestic violence at the Inter-American Development Bank, which is funding the study. “This could prove that the next generation of the labor force is also at risk. Not only women but men.”

That point, she says, could move policy makers, especially in an age of persistent gender bias.

Jorge Agüero, an economist at the University of California, Riverside who is a co-investigator of the project, is analyzing 14 years of data on domestic violence from Peru, Bolivia, Colombia, Honduras, Nicaragua, Haiti, and the Dominican Republic.

“So far, in our study, we are finding … that the negative effects of domestic violence are not limited to the women themselves, but also seem to be extending to their children,” says Mr. Agüero.

That includes having lower weight and height, a less likelihood of having been vaccinated, and more cases of reported diarrhea, compared to children whose mothers have not been victims of domestic violence.

The study is still on-going, so the researchers need to determine causality.

“If they are indeed causal, these findings will constitute new evidence,” says Agüero.

“The effects of domestic violence would be broader than we originally thought. Not only will they be affecting women, which is already bad enough, but they will be affecting the human capital accumulation of the next generation of workers.”

In a region of emerging economies, where GDP growth is paramount to presidents' success from Peru to Brazil, the findings will be hard to overlook.