Obama decision on gay marriage ripples through Latin America

Loading...

| Mexico City

When Argentina legalized gay marriage in 2010, many analysts – both for and against the union of same-sex couples – said that Latin America had blazed ahead of its northerly neighbor the United States.

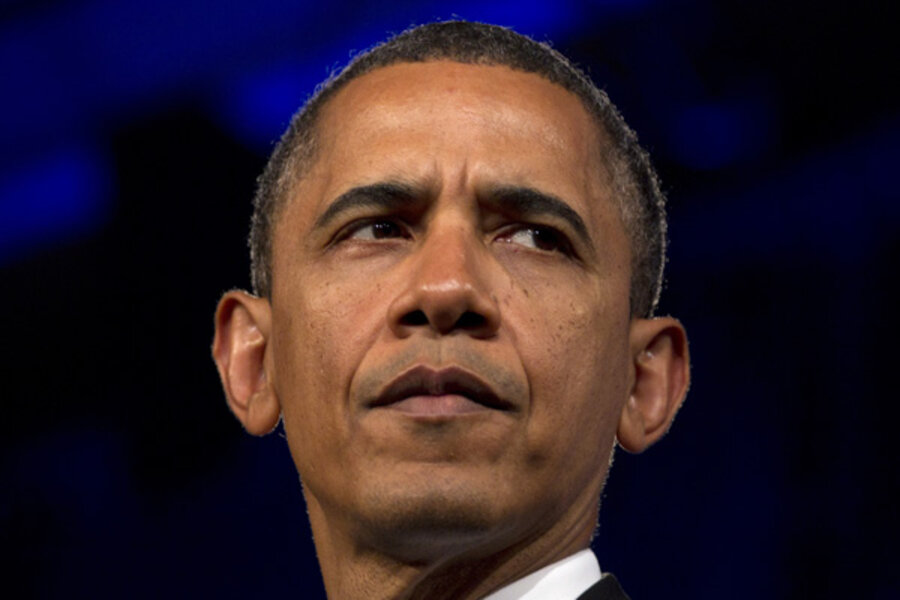

But with President Barack Obama's historic support of marriage between members of the same sex, the region is looking north, with expectations that the words of the US's top executive will reignite the debate across Latin America.

It is a risky stand in the US, with the nation squarely divided over the issue, but it has been just as controversial in Latin America: As countries have moved forward recognizing rights of gays and lesbians, from marriage, to civil unions, to adoption, the Catholic Church and conservative politicians have lashed out.

Many have questioned how Latin America, the most Catholic region in the world, has moved so far so fast on gay rights issues. It is not necessarily because residents of all countries embrace it.

“In Latin America, citizens don't support gay marriage that much,” says Margarita Corral, who worked on a 2010 survey on gay marriage by the Latin American Public Opinion Project (LAPOP) at Vanderbilt University.

In fact, support is lower in Latin America overall than it is in the US. In Latin America, respondents reported an average support level of 26.8 points on a scale of 100. That compares with 47.4 points of average support in the US, according to the LAPOP data. (Click here to read about the study's methodology and country-by-country results. Updated data is expected in coming months.) However, acceptance varies widely across the Americas, with Argentina and Uruguay showing relatively high levels of support, above the US, while El Salvador, Guyana, and Jamaica are at the very bottom.

This data shows that the more religious residents are, the less likely they are to support gay marriage. Part of the reason it has gained ground in deeply Catholic Latin America is that while the majority of residents identify as Catholic, they are not necessarily fervently religious. And at the same time, marriage is viewed in Latin America as first and foremost a civil act carried out by the state, says Simon Cazal, the executive director of the gay rights organization Somosgay in Paraguay.

Argentina has gone the furthest in the region with its 2010 national move to legalize same-sex unions. But Mexico City also grabbed headlines in December 2009 when the megalopolis legalized same-sex marriage. After Argentina, state courts in Brazil held that civil unions could be converted to marriages, and the top appeals court upheld those marriages last fall.

Those moves came after growing support for civil unions between same-sex couples across the region, first in Buenos Aires in 2002, and later in cities throughout Mexico and Brazil. Uruguay legalized civil unions nationwide, as did Brazil later.

Mr. Cazal says that while the Catholic Church has condemned the gay rights movement, the church is “one enemy,” he says, making it easier to fight than the disparate religious lobbies in the US (even though evangelicals have been gaining ground across Central and South America and are among the most vociferous opponents of gay marriage in the region).

President Obama, the first sitting US president to endorse gay marriage, told ABC News yesterday that "At a certain point, I've just concluded that for me personally it is important for me to go ahead and affirm that I think same-sex couples should be able to get married."

Conservative politicians across the world, including Latin America, quickly took a stance against Obama. "Barack Obama is an ethical man and a philosophically confused man," a Peruvian congresswoman Martha Chavez, told the AP. "He knows that marriage isn't an issue only of traditions or of religious beliefs. Marriage is a natural institution that supports the union of two people of different sexes because it has a procreative function."

Obama's words are likely to draw increasing reaction. "There is no doubt that this is going to have an impact, especially for conservative leaders who look to the US much more than ... to progressive leaders on this continent,” says Mr. Cazal of Somosgay.

“It is going to place the issue on the agenda and it is going to generate a debate in Latin America and around the world,” says Ms. Corral from LAPOP.

[EDITOR'S NOTE: The original story inaccurately represented how LAPOP measured support for gay marriage.]

Get daily or weekly updates from CSMonitor.com delivered to your inbox. Sign up today.