Chile earthquake relief: How one priest provides shelter for masses

Loading...

| Santiago, Chile

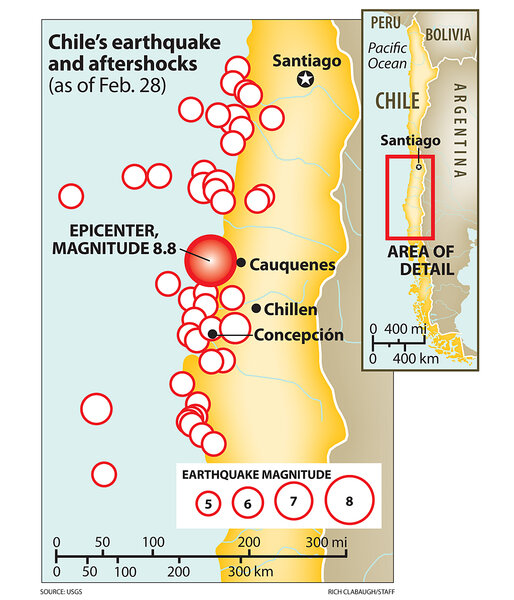

If anyone will play a crucial reconstruction role after the 8.8 Chile earthquake it is the Rev. Felipe Berrios, a Jesuit priest whose award-winning organization has in less than 15 years nearly gotten all Chilean families into permanent housing and expanded its work to 16 countries across Latin America.

Father Berrios, who set out to build emergency housing in Chile’s shantytowns in the late 1990s, had an ambitious goal when he founded a “Roof for Chile” in 1997: By the year 2000, he sought to construct 2,000 new homes throughout the country.

He reached the goal and kept going, expanding his organization regionally. The newer project, called “A Roof for My Country,” now aims to replace every shantytown in Chile by the end of 2010 – a goal the group still maintains is possible even after the 8.8-magnitude earthquake struck the country Feb. 27, killing more than 700, destroying more than 500,000 homes, and affecting an estimated 2 million residents.

IN PICTURES: Images from the magnitude-8.8 earthquake in Chile

“To get out of poverty you need a job, you need education and health services, but if you do not have a physical space to live in, the rest of it does not matter,” Father Berrios said in a December interview at his office on the outskirts of Santiago, which was bustling with college-age volunteers. “You need a place to be able to get a letter; you need to be able to say, ‘this is my home.’”

Rush to build emergency homes

While “A Roof for Chile” aims to find permanent housing for the 20,000 families registered as living in illegal settlements – when Berrios started the number was 135,000 – they are also rushing to build 30,000 emergency homes for those left displaced by the earthquake and tsunami in Chile.

“We have to respond to this crisis,” says Claudio Castro, the social director for “A Roof for my Country,” which also recently began working in Haiti in the aftermath of its 7.0-magnitude earthquake that left over 200,000 dead in January. The group plans to build 10,000 emergency homes in the next four years there with university students from across Latin America.

“But we will continue with the goal of having no [shantytowns] in Chile by this year,” says Mr. Castro.

What that means for Chileans is obvious in the Santiago shantytown of Ochagavia, where homes made of all shapes, colors, and materials are plunked down haphazardly. Before the earthquake, half the community was scheduled to move across the street to a little neighborhood behind a gate. There, 47 two-story brick homes neatly lined both sides of a paved road in December. A small park sat in the middle and a community center was under construction.

It wasn't possible to immediately verify whether that project had been damaged in the earthquake.

Mass migration to cities complicates things

In his mission, Berrios is helping to tackle the urban poverty that remains one of Latin America’s most stubborn problems. Continued mass rural migration over the past five decades has made the region the globe¹s most urbanized as newcomers build illegal sheet-metal shacks on the periphery of cities.

Worldwide, the United Nations estimates that 25 percent of the urban population lives in poverty, and the problem is worsening. By 2050, an additional 3 billion people will live in cities, most of whom will end up in slums.

“The demand is so monumental that there is no country in Latin America that is able to address it alone,” says Erik Vittrup at the Latin America and the Caribbean office for the United Nations Human Settlements Program in Rio de Janeiro.

Three phases

A Roof for Chile carries out its work in three phases. First, construction of temporary homes; second, bringing in education, social services, and microcredit programs while helping families find land to build permanent homes on; third, creation of sustainable neighborhoods.

On a recent day in Ochagavia, Elsa Gonzalez, a community leader here, emerged beaming from a meeting of A Roof for Chile that focused on helping half the community find land for new homes. “What I most long for is having a faucet with water running from it,” said Ms. Gonzalez, who is saving money for the small down payment, a requirement for each resident. She’s building her nest egg by selling hot dogs and snacks on street corners. “I cannot wait to be able to flush [my own] toilet,” she says.

By the bicentennial of Chile’s independence on Sept. 18, 2010, A Roof for Chile seeks to have each Chilean family, like the Gonzalez family, either moved into or in the process of owning legal title to their land. By year-end, the group plans to have branches in every nation in Latin America. Their newest office opened in Bolivia last year and the next on the list is Panama. They have also begun trying to raise funds in the United States, particularly among Latinos in Miami, New York, and Los Angeles.

Earlier in December, Berrios explained that after “A Roof for Chile” meets its goals in Chile, the organization plans to tackle crime and justice and other types of discrimination. The reconstruction of the country will be a first priority now, says Castro, who began working for the organization as a volunteer, and like many former college interns and volunteers, now holds a senior post. “It will be complex,” he says. “We still do not have a number of how many people are homeless.”

IN PICTURES: Images from the magnitude-8.8 earthquake in Chile