Haiti earthquake: Outside Port-au-Prince, Haitians say they've been forgotten

Loading...

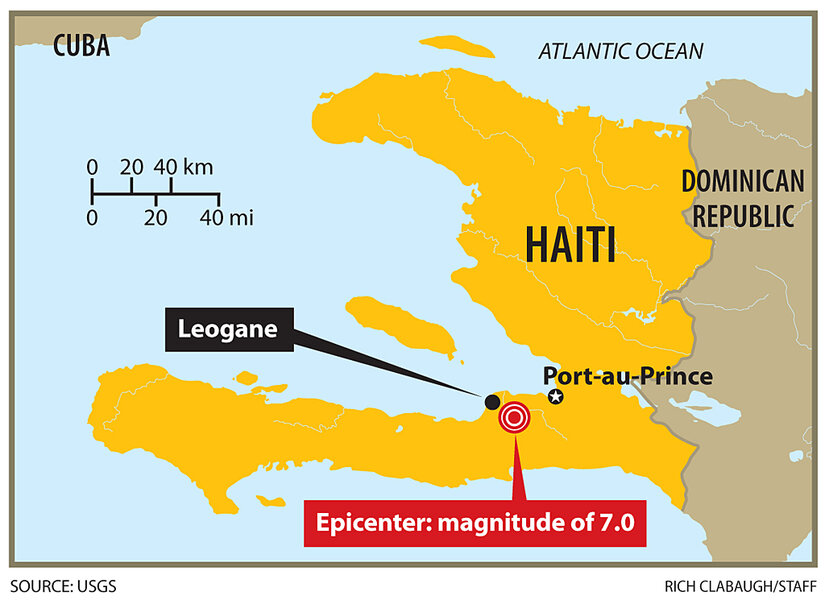

| Léogâne, Haiti

This coastal town 20 miles west of Port-au-Prince, framed by the trim of sugarcane fields and banana trees, had its heyday as a French colonial outpost in the 1700s.

But after last Tuesday's 7.0 earthquake, Léogâne, Haiti, will be known as the epicenter of what some are calling the worst humanitarian crisis in recent history.

Its downtown has the eerie feel of the “day after.” The main streets are virtually empty, save residents trying to recover the bodies buried in the rubble. Only the brick arches of the main Roman Catholic Church, Saint Rose of Lima, remain standing.

Injured children moan on the ground outside their collapsed homes, their broken bones and wounds left unattended as a sense of being forgotten grows.

While Haiti's capital, Port-au-Prince, is overtaken by international rescue teams, and harrowing images of the quake´s aftermath have generated an outpouring of international aid, residents in outlying towns such as Léogâne say they have been left to fend for themselves.

“We are alive, so God has been good to us, but the government has not done anything,” says Jean Brunel Lemaire, whose house, which he shares with his family and his brother´s family, has crumbled to the ground. Their neighbor´s house also fell, killing all five people inside. And all five remain buried there.“We are the same country, but they are only focusing on Port-au-Prince," says Mr. Lemair. "They are being negligent and irresponsible.”

Historical legacy

Léogâne shares a storied place in Haiti´s colonial history, with architecture that had been preserved through the centuries.

Now, a giant crack splits the main highway into town in two, leaving a ditch with depths of up to 30 feet. Officials estimate that 80 to 90 percent of the buildings in the town, which has about 150,000 residents, were heavily damaged.

Residents are sleeping between banana trees. The cemetery looks like a bulldozer razed it; one 1917 tombstone looks as if it had been angrily thrown on the ground.

The downtown is a booby trap of downed telephone poles and lines as well as bricks and boulders.

On one block, in a cruel fit of irony, every single building is collapsed except for the funeral home. Both the high school and elementary school are gone. Where the elementary school has crumbled, a little school desk lays on its side in the road.

Gina Sagesse lost her home and her three-year-old girl. She and her husband, desperate and mourning, headed to the main plaza with their four children in front of the church because it was the only large open-air space in town.

They have erected wooden poles, and hammered tin sheets in place for walls and a roof.

“We are waiting for the international community to come here and help us,” says Ms. Sagesse, holding up a photo of her dead child. “We do not know why they have not come.”

But aid is coming.

One week later, relief starts

Shortly after her comments, an aid organization drove past the plaza here, but did not stop. Later, a military helicopter flew overhead, as residents looked expectantly to the sky. Sri Lankan officers from the United Nations closed off a bridge and stretch of a highway to operate as an airstrip for relief efforts. Officer Anil Gunawarre says that one plane landed Sunday, carrying water.

The White Helmets from Argentina also arrived Sunday with a team of 17 doctors. They had already performed 600 treatments and delivered two babies, says an exhausted Esteban Chala, the chief coordinator for the group, who says that demand was so high when they arrived – the first medical team to get there, he says, nearly five days after the quake – that they performed them in an open field. They have eight seriously injured patients who require hospital treatment, but he says they were turned away from Port-au-Prince because all facilities are saturated.

“We need double the amount of doctors,” he says. “The people here need food and water, and there is nothing.”

Back in the corner of the Lemaire family, who distill moonshine from sugarcane stored in big wooden barrels, lives, neighbors say that not a single aid worker has come to see them.

“It is the same common story. The outlying areas are always forgotten,” says Fritz Lemaire.

The 10 of them are sleeping in their front yard, where piles of kindling collected for fire to melt sugar sits in a pile, their mattresses plopped down next to chicks prancing across the mud and dirty pigs roaming around. Some do not have a single sheet, and they worry about what will happen when the rains come.

The smell of rotting flesh overpowers the air next to the Lemaire house, and they say they worry about disease if rescue teams do not come soon.

Hardly a single structure stands on their street, called Rue Poudriere, and even though they are trying to support one another, each of them has losses few can imagine.

Even in this deeply spiritual country, where so many have said that the earthquake must be their country´s fate, they worry about their faith being shaken.

“The church is gone,” says Amulette Agustin, an elderly woman, walking barefoot down the street. That, she says, it what saddens her the most.