Chile, once Latin America's economic model, now overtaken by Brazil

Loading...

| Santiago, Chile; and Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

For two decades, Chile was the “teacher’s pet” of Latin America, the student who always brought home straight A’s.

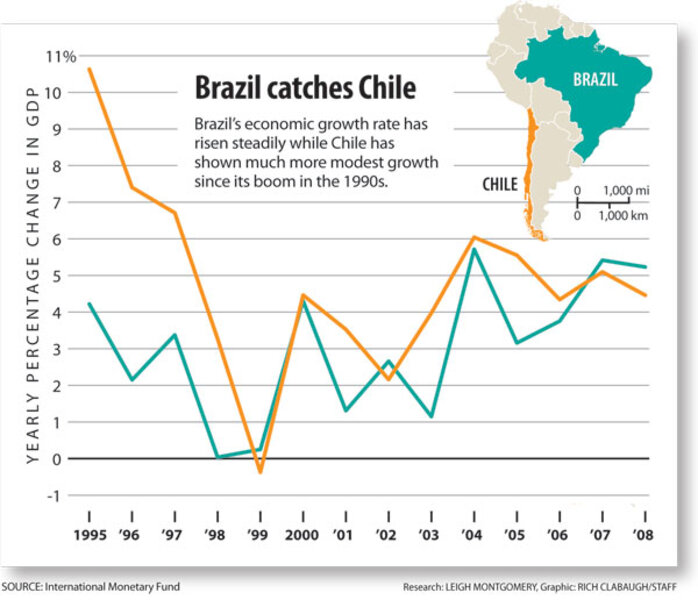

Economists gushed that the Andean country’s commitment to free-market policies and democratic reform made it a model for the developing world. And as Chileans enjoyed the trappings of a sustained average growth rate of more than 5 percent per year, poverty plummeted from 40 percent to 13.7 percent. But in the past year, Chile’s gold star has gone to its hulking neighbor to the east, Brazil.

The agricultural juggernaut just won its bid to host the 2014 World Cup and the 2016 Olympics; it discovered vast oil deposits that could turn it into a major oil exporter; it was one of the last countries to be pulled into the global economic crisis and one of the first to pull out.

To be sure, the so-called Chilean “miracle” that constructed the most solid economic foundation in Latin America still stands, and some of its slower growth today is merely a result of its own maturation. But Brazil is finally claiming new status in the region, and not just for its size.

“We always looked at Chile as something better than us,” says Arthur Ituassu, a professor of international relations at the Pontifícia Universidade Católica in Rio de Janeiro. “There is a growing sense in Brazil that we are now the major actor in South America.”

Promise finally fulfilled

This is not the first time that Brazil has been heralded as the world’s rising star. In the late 1960s and early ’70s, the country was growing at an average rate of 11 percent a year. But the oil shock of 1973 stifled that rise, and economic woes, conbined with political ones, characterized the 1980s and early ’90s. While Chile was experiencing its “golden decade,” Brazil struggled through its “lost” one.

Yet today, with more than a decade of stable institutions and sustained growth, Brazil is finally living up to its promise.

Foreign investment, for one, has poured in. Investors are drawn to everything from biofuels to soybeans. Between 1994 and 1998, Brazil attracted an average of $14 billion annually in foreign direct investment; in 2008 that figure skyrocketed to $45 billion, according to the United Nations’ Economic Commission on Latin America and the Caribbean, based in Santiago, Chile. By comparison, Chile brought in $16.7 billion in 2008.

Brazil’s economy is vulnerable, especially as its currency, the real, has surged against the dollar, threatening exports. But inflation is under control, foreign reserves have been built up, and it has diversified its commodities trade. The government has helped to break 19 million people out of poverty since President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva took office in 2003. His government raised minimum wages, augmented a conditional cash-transfer program, and helped create some 8 million formal jobs. Today, at 7.5 percent, the unemployment rate is below precrisis levels.

Chile more open than Brazil

Chile remains an economic stalwart. It also pulled out of the economic crisis solidly, using the windfall from copper exports saved during boom times. It maintains a strict fiscal policy and its 21 trade deals with 57 nations reflect an economy that is much more open than that of Brazil. It consistently ranks as the least corrupt government in Latin America and will this month become the 31st member of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), a group of top developed nations.

“I would say our image in the region is extremely positive,” says Juan Gabriel Valdés, the executive director of the government’s Chilean Image Foundation. “We know that we are observed and studied.”

Still, some in Chile are starting to grumble. While it averaged 8 percent growth from 1987-97, it now grows at about half that rate. Chile needs to regain its momentum, say critics, and work out kinks such as lost productivity and rigidity in labor laws.

“Chile is like a B student today. It is not bad, but it is not brilliant,” says Felipe Morandé, dean of the economics department at the University of Chile and an adviser to Sebastian Piñera, the right-leaning candidate who won the second round of presidential elections on Sunday. Mr. Morande says part of Mr. Piñera’s appeal is voter faith that he can revive the economy.

But Brazil now overshadows Chile, especially with Lula, its wildly popular leader whom President Obama called “the most popular politician on earth.” Ricardo Ffrench-Davis, an economist and former central bank official, says Brazil looks so good partly because it used to look so bad. “Two years ago, Brazil was growing much less than Chile,” he says.

Both countries face challenges ahead; both need to improve education and bridge divides between rich and poor. But their recovery from the economic crisis, as well as the strong rebounds in other nations such as Peru, bodes well for the future of the region, says Carlos Furche, head of trade in Chile’s government.

And those in Chile say they welcome the success of Brazil, which they view not as a rival but as a boon: A growing Brazil buoys everybody.

“The importance of Brazil’s emergence,” says Thomas Trebat, a Brazil expert at Columbia University in New York, “is that it shows you that growth can occur in Latin America in more places than just Chile.”