Organic coffee: Why Latin America's farmers are abandoning it

Loading...

| Guatemala City

Some 450,000 pounds of organic coffee sit in a warehouse here, stacked neatly in 132-lb. bags. It’s some of the world’s best coffee, but Gerardo De Leon can’t sell it.

“This is very high quality and it’s organic. But ... the roasters don’t want to pay extra these days,” says the manager of FEDECOCAGUA, Guatemala’s largest growers’ cooperative, which represents 20,000 farmers.

Mr. De Leon is asking $2 per pound for the green (unroasted) coffee, about 50 cents more than the going price. But he says he’ll soon have to sell it as conventionally grown coffee, which sells for less.

That’s why many Mesoamerican farmers here are starting to give up on organic coffee: The premium price that it used to fetch is disappearing.

From Mexico to Costa Rica, at least 10 percent of growers have defected in the past three years, estimates the Center for Tropical Agricultural Research and Higher Education in Costa Rica (CATIE). Researchers say that each year, about 75 percent of the world’s organic coffee comes from Latin America.

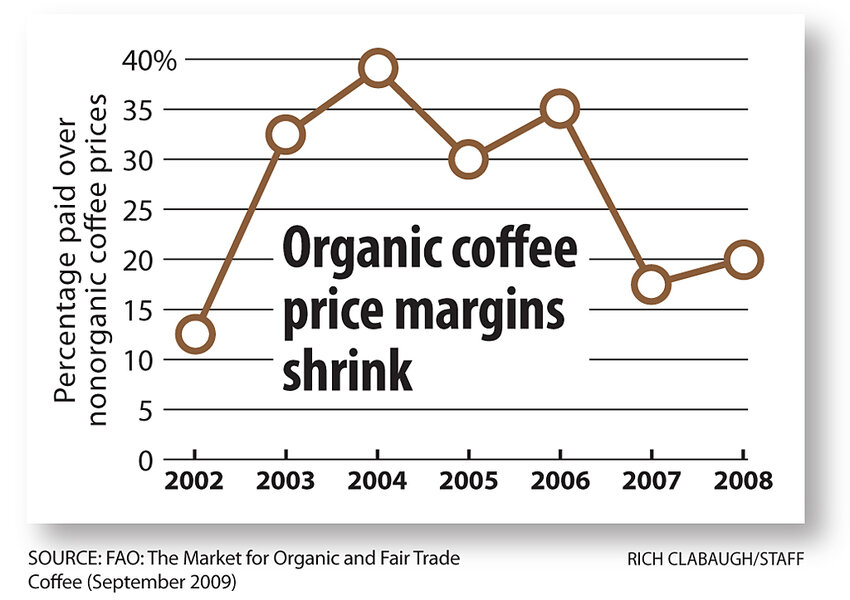

Farmers have returned to the chemical fertilizers and pesticides that increase production, albeit at a cost to the environment. Although organic still pays a premium of as much as 25 percent over conventional coffee, it’s not enough to cover the added cost of production and make up for the smaller yields. For consumers, the defections threaten to make the coffee harder to find.

“This is a critical point for organic coffee. It was starting to make the conversion to the mainstream,” says Jeremy Haggar, who oversees the research for CATIE. If farmers continue to abandon organic coffee, “prices will definitely go up and it will return to being a niche product.”

'Promised economic benefits'

Under specialty “green” labels at places like Wal-Mart and McDonald’s, organic beans and brews have become cheaper and more widely available recently. Last year, North American sales reached a record $1.3 billion, a 13 percent increase from 2007.

Major retailers already struggle to fill demand. Seattle-based Starbucks Corp., the world’s largest coffeehouse company, said just 3 percent of its coffee purchases, about 10 million pounds, were organic last year.

“Our purchases of certified organic coffee are limited due to the limited quantities available worldwide and the constraints of the organic certification system for farmers,” the company said in a statement issued in response to questions.

The expense of organic certifications, composts, and the losses incurred by pests and other factors mean growing organic costs about 15 percent more than growing conventional crops, Mr. Haggar says. More notably, by using chemical fertilizers a farmer can coax about 485 pounds of coffee out of one acre, versus 285 pounds per acre on an organic farm, according to CATIE.

With coffee prices rebounding from the historic lows of a decade ago, there’s little financial reason for growers to continue raising organic beans.

“I can sell [nonorganic coffee] to a coyote [middle man] for around the same price [as organic], a little less, and I can use whatever I want on the coffee plants – fertilizers I can buy, pesticides,” says Jose Perez, who stopped growing organic coffee on his three-acre farm in Guatemala last year. “I can grow a lot more this way.”

Mr. Perez is an example of what World Bank coffee researcher Daniele Giovannucci says was an empty promise made to growers. “Many farmers ... were promised economic benefits by those that wanted them to convert, which was a very bad idea,” he writes in an e-mail, “and [this trend] is bearing the fruit in their dissatisfaction.”

Organic demanded, but not at higher price

A decade ago, with coffee prices bottoming out and at the urging of some development organizations, tens of thousands of Latin American farmers began to convert their fields to producers of certified organic products. To do so, farmers followed strict rules set by a handful of agencies, including the US Department of Agriculture, that require soil be free of pesticides and chemical fertilizers for three years.

After making the conversion, they would be supplying a growing market that paid as much as 40 percent more. They would also be preserving their land. Conventional farms apply as much as 250 pounds of chemical fertilizers on every acre. “And they use tons of pesticides that are harmful to human health and affect biodiversity,” Haggar says. Organic farms, rich with flora, trap more carbon than their conventional counterparts, an important benefit for a crop threatened by climate change.

However, the farmers don’t receive the financial benefits of organic coffee until they are certified, meaning they were expected to absorb extra costs for three years. Many went into debt. Now, they are quitting organic farming.

“When you’re a small organization like ours, it’s already difficult to survive against the big growers. So when you lose members, it hurts you a lot,” says Marvin Lopez, manager of APODIP, a Coban, Guatemala-based cooperative of organic growers that lost half of its members, about 380, last year.

“I get calls every day from buyers in the US who are asking me if I have any organic [coffee] available. But then I tell them the price, $2 per pound,” De Leon says, pointing to an e-mail with an offer to pay $1.50 per pound. “So, the coffee just sits there.”