Will Nigeria accept US and UK help, to stop Boko Haram? It should.

Loading...

A version of this post will appear on the Africa and Asia blog. The views expressed are the author's own.

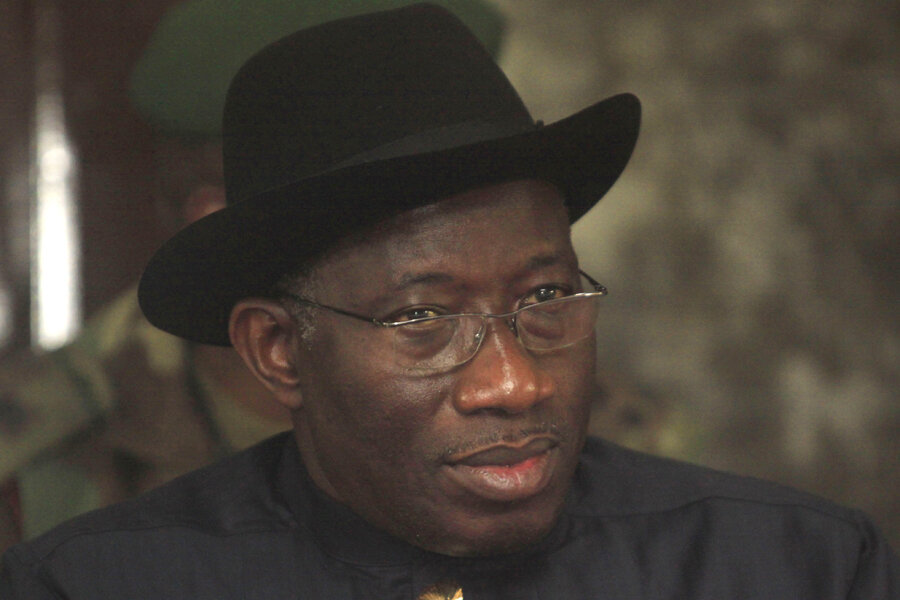

Nigeria’s seeming inability to stem the rise of Boko Haram, a shadowy Islamist rebel insurgency, poses severe existential threats to Africa’s largest economy and democracy and to the continuation of President Goodluck Jonathan’s presidency.

This month’s kidnapping of as many as 275 girls from a northern Nigerian training school, where the girls were sitting for exams, is only the latest of dozens of attacks perpetrated this year and many more in previous years by Boko Haram against school children, Christians, and secular representatives of the Nigerian government.

As of this week, more than 200 of the girls were still unaccounted for, presumably taken as cooks, domestic workers, and sex slaves to serve the young men of Boko Haram. Many have been married forcibly to their captors and some have been taken into nearby Cameroon.

[On May 4 Mr. Jonathan vowed to "get them out," regarding the school girls, and said he has twice spoken to President Barack Obama on the subject.]

Earlier in the month, Boko Haram blew up buses in a commuter town on the outskirts of Abuja, Nigeria’s capital. In 2014, it also attacked six other schools, seven churches, burned and pillaged two rural settlements, and bombed several markets, mostly in the Muslim-dominated northeast.

It also blew up a UN building in Abuja in 2012 and has enthusiastically taken responsibility for bombings, assassinations, and school and village destructions ever since 2011.

Boko Haram is responsible for 1500 persons whose lives have been lost in raids so far this year, and more than 3600 overall. The government claims to have killed an equal number of the members of Boko Haram, including one of its key leaders. But those losses are hard to confirm and government forces seem reluctant to pursue Boko Haram, even after the latest kidnapping.

But why Nigeria’s formidable army, which contributed to peace making in Liberia and Sierra Leone, and was mobilized in Mali, cannot contain Boko Haram is not clear.

Nigeria is regarded as a country where corruption runs rampant, even in the Army; corrupt practices may indeed have distorted or slowed the Nigerian military´s battle against Boko Haram.

But a lack of good intelligence about Boko Haram and its hideouts (some of which seem to be in Niger and Cameroon) probably matters more, as does Nigeria´s professed reluctance to avail itself of US assistance, probably in the form of aerial surveillance and communication interceptions.

The composition of Nigeria´s security forces, with a preponderance of Muslim officers, but with many Christians, is not a factor. Nor is their usually well-praised leadership. The country’s political will for the fight is also not at issue. Execution and effort seems, nevertheless, to be lacking.

Boko Haram is an indigenous insurgency that has almost no local support. Its name means “opposition to Western education” or “Western education is sinful.” But the mostly Muslim population in the northeast, and especially Borno State base, where Boko Haram is from, actively seeks as much Western (modern) educational opportunity as possible.

Since Borno and Northern Nigeria are less well-educated than Southern Nigeria, Boko Haram opposes the popular and very widespread desire throughout the nation´s north for more and more schooling.

Boko Haram claims to be affiliated with Al Qaeda, and Boko Haram is on several global terror lists. But not only is the Boko Haram leadership and its goals fundamentally murky, so is the real nature of its ties to Al Qaeda. So far Boko Haram may have recruited youthful followers and youthful killers more on the promise of riches and loot than on account of its nihilist ideology.

The movement now seeks to create a new caliphate in Nigeria, governed by sharia law, but it started out as much more of an effort to extirpate outside education than it did to impose an ideology or fundamentalist Islam.

Abukakar Shekau, the group's nominal leader, has largely been silent since an inflammatory video in 2010. He has not recently offered a vision for the reborn Nigeria, preferring to denounce, denigrate, and destroy more than to outline a resplendent future for Nigerians.

That is why Boko Haram would be considered a cult more than an insurgency if its militias had not massacred so many innocent and mostly young, unsuspecting, civilians, and caused so much school – and church-targeted mayhem.

Boko Haram’s founder, Mohammed Yusuf, in 2001 proclaimed his antipathy to Westernized education and specifically rejected Western scientific thinking, especially the theories of Charles Darwin.

But by the time Yusuf was killed by security forces in 2009, he had gathered only a small and not very militant following.

It was only after Shekau, his successor, sprung 150 alleged Boko Haram adherents from a northern prison that the movement began to gather momentum, with a few raids in 2011, more in 2012, and major outrages (29 students burned in one incident and 40 more in another) in 2013.

Boko Haram will continue to massacre innocent children and destroy Western cultural symbols and edifices until President Jonathan manages to gain assistance from abroad, from African neighbors, and find ways to mobilize his soldiers effectively to pursue Boko Haram into their forest camps and urban hideouts.

What Jonathan needs first to do is to accept US offers of technical help, certainly satellite, and drone-provided information showing the whereabouts of Boko Haram. US technology could also offer timely warnings of Boko Haram likely attacks.

Ultimately, Jonathan should ask for British or American special forces, as in Uganda’s welcoming of 100 American advisers in its search for Joseph Kony, leader of the Lord’s Resistance Army. Without such aid, the pursuit of Boko Haram may continue to accomplish too little, and always be late.