Congo’s wars uprooted her life. But they couldn’t silence her poetry.

Loading...

| Goma, Congo

Until recently, Sylvie Baziga shouted her truth.

Every Saturday morning, the high school student joined a group of fellow young writers who gathered in a courtyard here to recite poetry. Performed a cappella or over a melodic backing track, their words took the pulse of the wounded region around them.

I am that woman who draws hope and resilience, a light in this world in distress.

A star shining with a thousand colors of love.

Every day, I pick up pen and paper to bring my most intense emotions to life. My words tell my story.

Flanked by walls made of black lava stone, the young poets of the Goma Slam Session denounced the pillaging of the eastern Democratic Republic of Congo’s abundant natural resources and the indifference of its political elites. They raged against poverty, rape, and the pain of being forced to flee from home.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onIn eastern Congo, a generation that has grown up in the shadow of war, displacement, and corruption finds hope and release in spoken-word poetry.

“When we write, we find ourselves facing our demons, our anger, our fears,” explains Ms. Baziga. “It’s a form of therapy.”

Then, in an instant, it was all gone.

In late January, a rebel army called the March 23 Movement (M23) advanced on the city. In less than a week, fighting killed at least 1,000 people. Bodies were left piled in the streets. Ms. Baziga’s two young brothers wailed as gunshots whizzed past their house.

Suddenly, the idea of shouting your truth from the rooftops was not just reckless. It was completely impossible.

Words of war

Built at the edge of an active volcano, Goma mirrors its people: lively, damaged. Until the recent rebel advance, the outskirts of the city of 2 million were crowded with huge camps of makeshift white tents. Here, hundreds of thousands of people took shelter from fighting that has crashed in waves over this part of Congo for three decades.

Ms. Baziga knew that little more than chance separated her life from theirs. She, too, had her life ripped up by the roots by the fighting. In February of last year, she fled her home in the nearby town of Saké when it was attacked by M23 fighters. She did not live in the camps only because she happened to have an uncle in Goma who could take her in.

War has become our sun, joy has faded, and we put on a fleeting smile to cover the scars, the tears, and regrets.

Freedom has fled our land, insecurity blows everywhere and weakens our dreams.

In Saké, Ms. Baziga was part of a group of slam poets, and when she arrived in Goma, she found a thriving scene in the genre. A kind of rhythmic freestyle poetry, slam shares many traits with hip hop. Poets perform their pieces aloud, in front of audiences, sometimes in a competitive format. The genre also has a reputation for sharp social commentary.

In recent years, slam has found fertile ground in eastern Congo, where a generation of young people have grown up in the shadow of a series of brutal civil wars.

Since the 1994 genocide in neighboring Rwanda, a string of rebellions have ravaged the region, causing armed groups to proliferate. The fighting is fueled by the region’s vast mineral wealth, and driven by a tangle of ethnic and political conflicts, as well as decades of bad governance. In every iteration of the fighting, those who suffer most are the region’s civilians, who have lost their homes and loved ones, and been left resourceless and vulnerable.

Slam provides the rare space where young Congolese who have come of age in this turmoil can speak freely about their anger and frustration.

“At some point, I wondered if I should take a weapon and fight for the country, like some of my friends did. Then I realized that I already had a weapon, my pen,” says Steven Muhindo, a young slam artist in Goma who, like Ms. Baziga, fled Saké last year. “Slam is a way to denounce what upsets us. It is also a way to give hope to the people.”

Slam performances here are immensely popular, and clips are widely shared on social media. Last July, Bintou Keita, special representative for Congo to the United Nations Secretary-General, read an extract from a piece by a Goma slam poet in front of the U.N. Security Council.

Drowning out the guns

For Ms. Baziga the genre’s unbridled, incisive style came naturally. She started writing poetry at the age of 15, but seeing her words on a page always felt flat. She says instead she wanted to create poems that could drown out the guns.

“For me, it is a remedy that heals, that relieves the burden of sorrows,” she says.

But art is never apolitical, and in eastern Congo, slam often intertwines with activism. Poems tackle serious social issues like violence, corruption, and political malaise.

When M23, a rebel group backed by the government of neighboring Rwanda, took over Goma in late January, Ms. Baziga and her fellow poets began to fear what could happen if they continued to perform. So they canceled their weekly Saturday sessions.

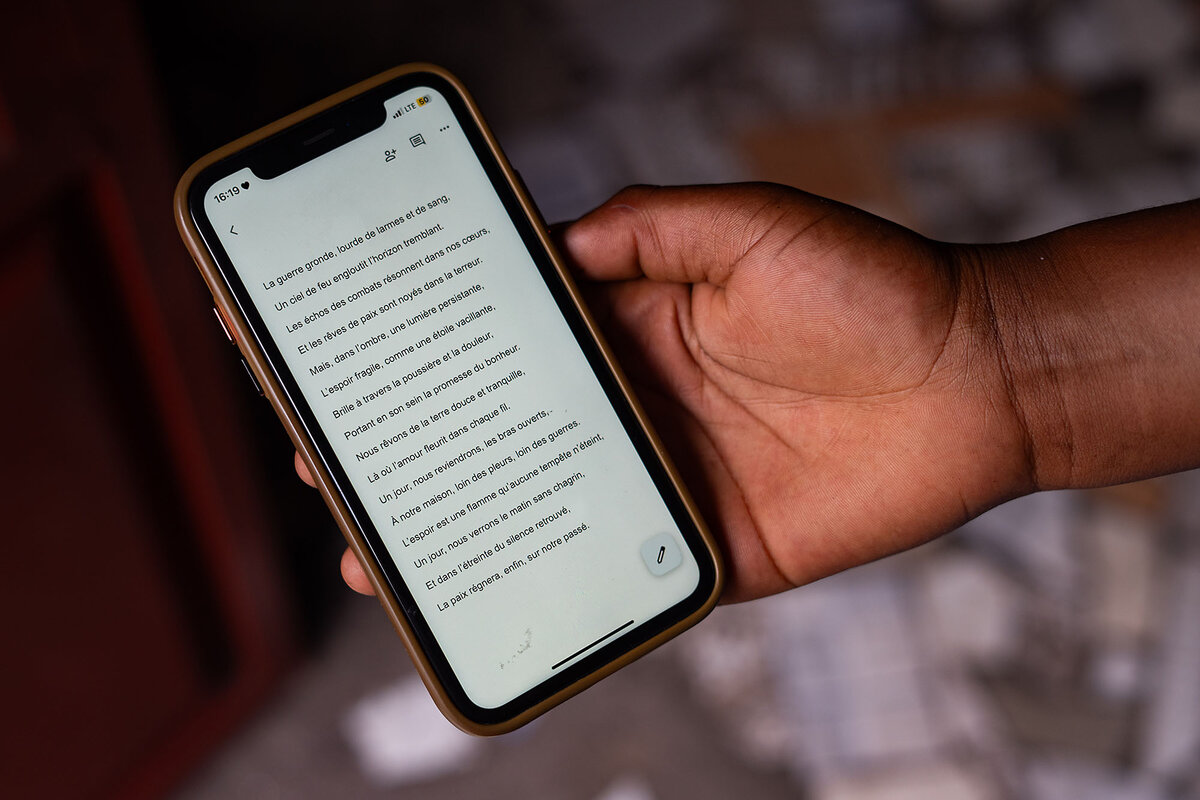

In their place, the group began sending each other poems on WhatsApp, trying to carve out a smaller, quieter space for self-expression there as they adjusted to the new normal of life under M23 rule.

These days, Ms. Baziga has no idea what will come next. Her school has reopened, but she is meant to take exams to graduate in June, and doesn’t know if they will be held in areas under rebel control.

“Taking up a pen, expressing what hurts me, is what keeps me alive,” she says.

In the heart of the Congo, hope remains.

Under the weight of the days, the sky murmurs,

Broken dreams, whispering souls.

But in our hearts, a flame rises.