Why rich oil reserves are a mixed blessing for Ugandans

Loading...

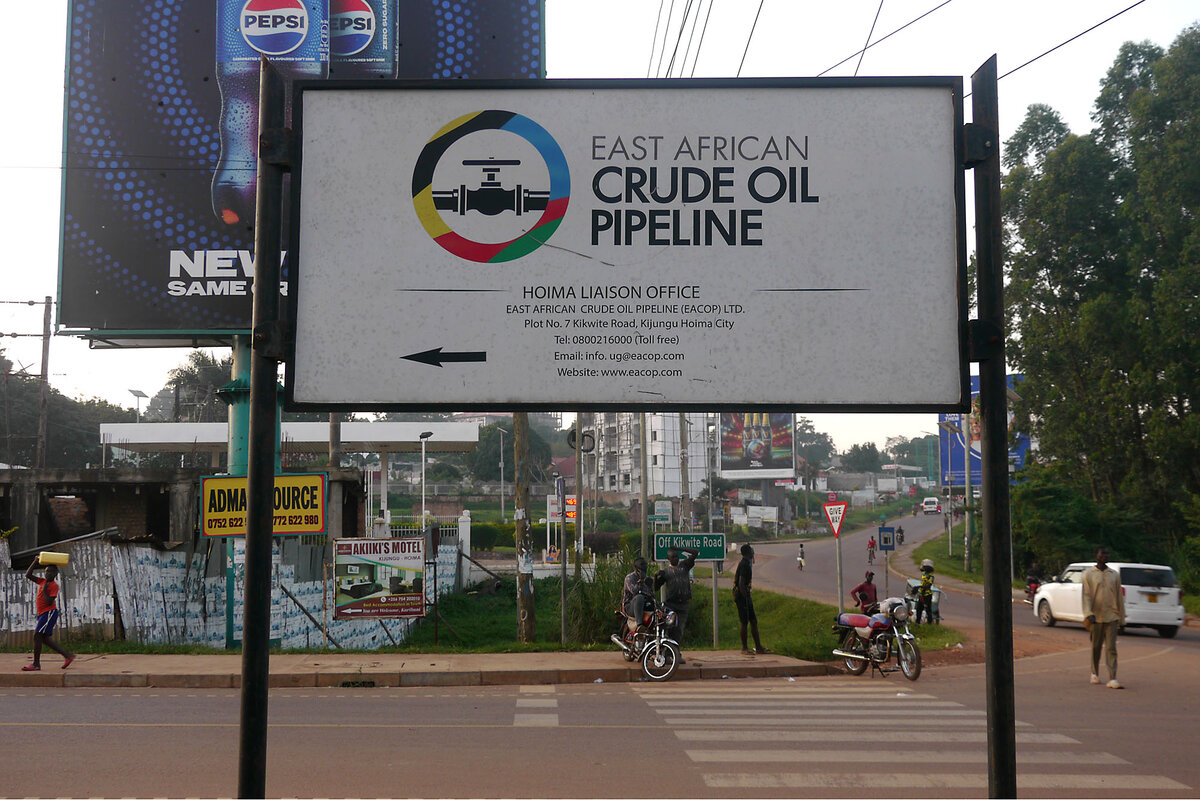

| Hoima, Uganda

Growing up in a fishing community on the cerulean shores of Uganda’s Lake Albert, Julius Tumwine listened to adults around him speak of oil with reverence.

In 2006, some 6.5 billion barrels of it had been discovered beneath the lake’s surface, a vast deposit that stretched into the earth under the houses and cassava fields where Mr. Tumwine and his friends played. Their teachers told them to study hard, because oil meant opportunity.

“We grew up with that mentality,” Mr. Tumwine says, a touch of bitterness in his deep voice.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onMany countries in the Global North became rich extracting fossil fuels from the ground. Now, many countries in the Global South say they should have the same opportunity. But a major pipeline project in Uganda poses the question: At what cost?

Nearly two decades later, the situation has proved far more complicated. Today, drills bore deep in the ground near Mr. Tumwine’s home, extracting oil in preparation for the opening of a controversial $4 billion pipeline. When complete, it will be one of the longest oil pipelines in the world, transporting Lake Albert’s oil 900 miles to the Tanzanian coast.

Uganda’s government says the project, led by French multinational TotalEnergies, will help catapult the nation out of poverty, just as fossil fuel extraction has done for countries around the world. “It is an opportunity, not just for the country, but for the people to benefit,” says Tony Otoa, chief corporate affairs officer at the Uganda National Oil Co.

But many living in the pipeline’s path are far more dubious. Mr. Tumwine says he has watched his community empty out as the oil company moved in. A report released in December by a group of local and international watchdogs documented harassment by state security forces guarding oil fields, as well as a series of forced evictions to clear the way for oil extraction.

“I don’t think it is me, or the community, who will benefit,” Mr. Tumwine says.

Rabbits fighting a lion

When it opens in 2027, the East African Crude Oil Pipeline (EACOP) will thread its way through 178 Ugandan villages, before snaking across Tanzania to the Indian Ocean.

TotalEnergies owns a commanding 62% stake in the venture, and the project is also backed by the China National Offshore Oil Corp., and the Ugandan and Tanzanian governments.

Mr. Tumwine’s home stands on land slated for the Kingfisher Oil Field, one of the two that will feed EACOP.

Despite his teacher’s predictions, the only oil-related job he could find when he left school was laying bricks for one of the construction companies in the project area. He says he made about $2 a day.

As oil-related activities escalated and drilling kicked off in 2023, he says residents began leaving. Some were evicted. Others packed up their belongings voluntarily, as oil rigs climbed toward the sky and the fishing that had sustained people for generations was restricted.

Disappointed and worried, Mr. Tumwine attended a community meeting about the impacts of oil organized by a Ugandan nongovernmental organization. Afterward, he began explaining the dangers of oil to his friends and neighbors.

But he knew the work was not without risks. Uganda’s long-ruling president, Yoweri Museveni, has vowed to protect the country’s petroleum sector at all costs.

For Mr. Tumwine, this turned out not to be an empty promise. In October 2024, he led a community meeting related to the pipeline project. Afterward, he says, four police officers arrested and beat him. His phone was confiscated, and he was held for three days on charges of inciting violence, before being released on bail, according to his bond sheet.

The watchdog report found that some 81 demonstrators had been imprisoned for protesting the pipeline between May and early September 2024.

“We are like rabbits fighting with a lion,” says Dickens Kamugisha, director of the Africa Institute for Energy Governance (AFIEGO), an advocacy organization in Uganda’s capital, Kampala. “I’m yet to see which people have benefited from this oil infrastructure.”

Oil Rich Motel

When completed, a network of feeder pipelines will carry crude oil drilled in Kingfisher to the outskirts of the small city of Hoima, which marks EACOP’s starting point.

In Hoima, discontent and fear mingle with hope. Not far from a sign advertising the “Oil Rich Motel,” Annette Aliguma sells cabbage from a rundown patch of road, as she has done for 20 years. The produce hawker says she is grateful for the pipeline because it will mean more people in Hoima, and that, in turn, will mean more customers. “There is excitement,” she says simply.

“Everyone has benefited. People are still benefiting,” asserts Mr. Otoa, of the Uganda National Oil Co. Roads leading to Hoima have been paved with support from the World Bank. He points to the thousands of jobs created by the oil sector.

But for the tens of thousands of families whose land lies in the pipeline’s path, those figures have little meaning.

One farmer in Hoima says the yams, millet, and mango trees she has planted will soon be uprooted to make way for the pipeline.

“People are suffering,” says the farmer, who asked not to be named because she fears retribution from oil companies and the Ugandan government for speaking about her community’s experience. “The little money they gave [as compensation] can’t buy anything,” she adds.

In total, more than 100,000 people will be impacted by the pipeline in Uganda and Tanzania, according to Human Rights Watch. According to the watchdog report, commissioned in part by the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH), displaced farmers have often been moved to smaller houses, or spent years waiting for compensation.

Still, efforts to protest the pipeline have met some success. Late last year, Uganda’s energy minister, Ruth Nankabirwa, conceded that the pipeline’s opening had been delayed by two years because of “campaigns against it.” Meanwhile, one major lender, Standard Chartered Bank, has already pulled out of the deal in response to the environmental concerns that activists have raised.

But for communities in the pipeline’s path, fear and uncertainty still loom.

“Everything is changing, day and night,” the farmer in Hoima says. “In five years to come, or 10 years to come, what will happen?”

A reporter in Hoima contributed to this story.