In Rwanda, progress and development scrub away an ethnic identity

Loading...

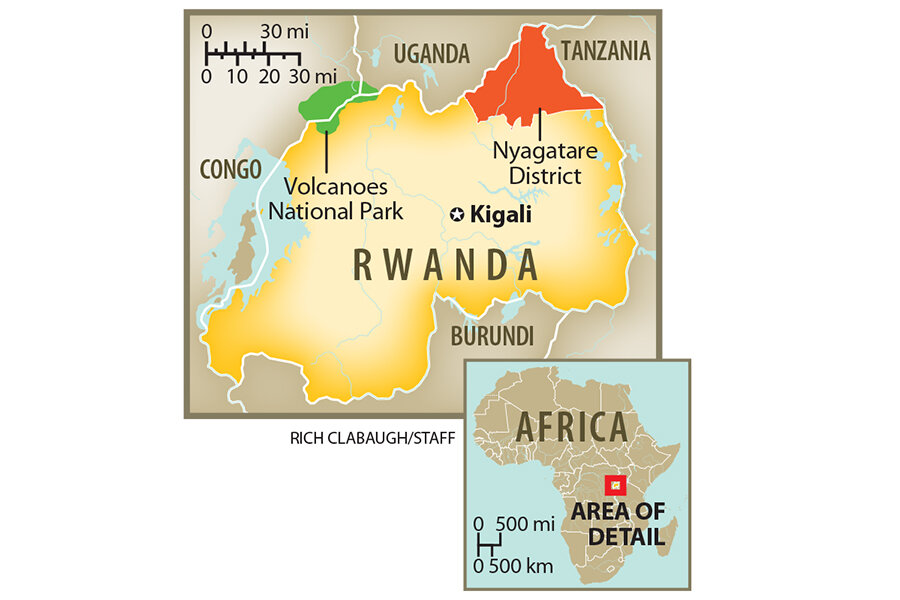

| Nyagatare District, Rwanda

The hills that back up against this village in northeastern Rwanda are blanketed by a tight patchwork of farmland, neat slices of green and brown earth heavy with sweet potatoes, beans, and cassava.

For nearly two decades, 87-year-old Theresa Mukanwari has stepped out of her stocky mud-brick hut each morning to look on this idyllic view.

“We can see now that government has brought development there,” she says jabbing a finger at the nearby farms. “But before, when I was younger, my people had more food.”

Dubbed the land of a thousand hills for its lush, undulating landscape, contemporary Rwanda is also a land of a thousand competing superlatives. It is the site of both the modern world’s most efficient ethnic genocide and one of its most remarkable post-conflict recoveries – Africa’s dark heart and its development darling.

Twenty-one years ago this month, crudely armed militias walked from village to village hacking their neighbors to death. When they were finished, more than 800,000 people were dead, the most civilians to be murdered in any three-month period in modern human history, including the Holocaust.

Today, Rwanda’s economy is growing briskly – an average of 8 percent annually – while life expectancy has doubled since the genocide, and the number of people living in poverty has declined steeply. Rwanda is the only country in sub-Saharan Africa on track to complete all of its health-related Millennium Development Goals, the United Nations’ global development benchmarks.

In-depth report: Amid growing prosperity, Rwanda's post-genocide generation comes of age

That transformation has been about scrubbing Rwanda clean of the ethnic identities that once tore it apart. The laws and policies designed to eliminate ethnicity from the public sphere, however, have not benefited people like Ms. Mukanwari, a member of the indigenous ethnic minority, the Twa.

Alternately ignored and exploited over the past two centuries by colonialists, as well as by the two major ethnic groups – the Hutu and Tutsi – the Twa seem to tiptoe along the borders of post-genocide Rwandan society. Officially recognized as neither victims nor perpetrators of the genocide – though they were both – the Twa have been afforded few opportunities to participate in either the country’s collective reconciliation or the material gains of its redevelopment – even when they take place only a hillside away.

Making up a sliver of 1 percent of the total population (the exact figure is murky, since the country no longer tabulates ethnicity in its census), they have been systematically and unceremoniously expelled from the thick forests where they once lived as nomadic hunter-gatherers. Most eke out a meager living as day laborers or makers of simple clay pottery.

But the Twa play an outsize role in demonstrating the potential complications of a postethnic Rwanda – their struggle for recognition an abrupt reminder of the identities that the country chose to submerge in order to outpace its murky past.

‘Almost no one seems to notice’ the Twa

“There is this idea in Rwanda that you can create a country where Hutu and Tutsi are unified and the ethnic hatred of the past is forgotten,” says Bennett Collins, a researcher on the rights of indigenous peoples at the University of St Andrews who works with Twa communities in the Great Lakes region of Africa. “But here’s the problem: There’s another group of people in Rwanda – the Twa – and almost no one seems to notice they’re there.”

Not so long ago, the Twa courted that invisibility. Before the 19th century, they lived as nomads in the region’s heavy forests, drawing on encyclopedic knowledge of the land to hunt elephants and forage for edible plants. But as farms and cattle grazing land slowly gnawed into their territory, many Twa reluctantly joined the society of the conquerers.

“Because they are the aboriginal people, the Twa had a pivotal role in the mythology of the land, and were always seen as having great power over it,” says Jerome Lewis, an anthropologist at University College London who has written extensively on the Twa. “If you wanted your crops to grow, you’d chop a finger off a Twa person and plant it in your field. And every royal lineage depended on having a Twa presence in its courts to bless the earth.”

In 1904 an American named Samuel Phillips Verner duped a small group of Twa and other Pygmies – a blanket term for indigenous central African forest peoples – into accompanying him to the St. Louis World’s Fair, where they were put on display and visited daily by throngs of tourists.

Two years later, one of the men, a Congolese named Ota Benga, was briefly exhibited in the monkey house at the Bronx Zoo in New York behind a plaque detailing his height (4 ft., 11 in.), weight (103 pounds), and age (23).

He “has a great influence with the beasts,” squawked one local newspaper, “even with the larger kind, including the orang-outang [sic] with whom he plays as though one of them, rolling around the floor of the cages in wild wrestling matches and chattering to them in his own guttural tongue, which they seem to understand.”

This brand of racist Western pseudoscience was nothing unique across colonial Africa in the early 20th century. But its role in Rwanda was especially insidious.

Here, colonial authorities attempted to read the complicated ethnic hierarchies they observed through the lens of Western race categories. Armed with scales, rulers, and calipers, they dutifully measured the skull radius, nose length, and bodily proportions of Rwandans and concluded that the minority Tutsis, with their lean, sharp “European” features, were the country’s natural rulers. Next came the more “bestial” Hutus, and finally, most primitive of all, the Twa.

By the 1930s, Belgian authorities had successfully flattened centuries of complex ethnic politics into simple labels, gifting every Rwandan with a mandatory ID book that billed him or her as either Hutu (85 percent), Tutsi (14 percent), or Twa (1 percent), and lining up preferential access to schools, jobs, and other resources for the privileged Tutsi minority.

As once-fluid ethnic hierarchies calcified, their meanings in people’s lives became more absolute. Until they became worth killing for.

Caught up in the violence

Modern Rwandan history folds neatly in half – before 1994 and after. In the center, in the dark groove, stands what is perhaps the modern world’s best-orchestrated mass killing.

Between April and July 1994, close to 1 million people – Tutsis, moderate Hutus, and Twa – were slaughtered by extremist Hutu militias known as theinterahamwe.

“The genocide is officially called a Tutsi genocide, but I’m confident that the Twa suffered inordinately in the killings compared to any other group of Rwandans,” says Mr. Lewis, the anthropologist. “They had no allies. They were hit from every side.”

The stories Twa tell of the genocide depend largely on where you find them. Many who lived alongside Tutsis were murdered alongside Tutsis. In fact, more than a third of all Twa living in Rwanda died in the killings, according to Lewis’s research, which involved interviews with hundreds of Twa survivors. Official statistics do not exist.

Some Twa also took up arms for the interahamwe – willingly or under coercion. And thousands more simply fled the country alongside Hutus, landing in the militia-controlled refugee camps huddled along the border between Rwanda and eastern Congo.

“Others were running, so we ran, too,” says Apollo Saasita, mirroring a sentiment expressed by many Twa who survived the genocide. The violence was not about them, they said, but they couldn’t avoid its reach. Along with those in his village in western Rwanda, Mr. Saasita fled across the border into Congo, where he stayed for nearly three years.

In-depth report: Rwanda, the world's swiftest genocide

But dispossession was nothing new to Saasita and his family. Just a decade earlier, Saasita, who grew up among a nomadic band of Twa in the foothills of the jagged Virunga volcanoes, had been evicted from his home to make way for conservation projects in the area. Today, those roaming the land he grew up on are mostly khaki-clad tourists in search of the region’s famed mountain gorillas.

Saasita, meanwhile, stays with three generations of his family in a sour-smelling three-room mud hut on the park’s fringes. He spends his days waiting for nearby farmers to call for day laborers or visiting tourists for whom villagers perform improvised dances for tips.

“It would be better if we had land,” he says.

Not all Twa, however, feel completely left behind by genocide recovery. In the years that followed, Rwanda’s government faced the nearly impossible task of transforming the paper-thin category of “Rwandan” into an identity that could mean something to both those who committed genocide and their victims.

They built “reeducation” camps to teach returnees about the new Rwanda and banned the ethnic labels “Hutu” and “Tutsi.” A slate of new laws made “ethnic divisionism” and “genocide ideology” serious crimes, while local courts, called gacacas, were established to bring justice to communities torn apart by murder.

For at least some younger Twa, that meant a new start in which they might outrun the overt discrimination that had confined previous generations to the fringes of Rwandan society.

In 2014 Richard Ntakirutimana became the first person from his village to graduate from university on a government scholarship earmarked for Rwandans from “historically marginalized” backgrounds. He now uses his law degree to manage a nonprofit group in Kigali, the capital and largest city in Rwanda, that teaches Twa communities farming skills and money management.

“The way it is in Rwanda now means that those of us who advocate for the Twa are advocating for a group that, officially, does not exist,” he says.

But Lewis says the silence around ethnicity in Rwanda today has not so much eliminated ethnic tension as driven it underground. Some activists working with Twa communities would not speak on the record for fear of government reprisal.

More generally, the Rwandan government’s wide application of “ethnic divisionism” and “genocide ideology” laws against its detractors has raised international alarms that the laws have become more a tool of repression than development.

“Space for criticism of the country’s human rights record by civil society was almost nonexistent,” reported Amnesty International in its 2014 report on Rwanda. “The human rights community remained weakened, with individuals taking a pro-government position in their work or employing self-censorship to avoid harassment by the authorities.”

And for the vast majority of the Twa, the idea of being absorbed into a wider Rwandan society remains little more than a pipe dream.

Like many Twa, Maria Theresa Mukaburasiyo has spent her life working as a potter, expertly sculpting cooking pots from the gray clay she gathers from a swamp two hours from her village south of Kigali.

It’s an occupation, she says, that’s increasingly being written out of history – both by cheap metal cookware and government regulations that make it difficult to gather clay from the swamplands.

But, speaking in the sideways manner many here use to discuss ethnicity, Ms. Mukaburasiyo says she would never be able to shed the ethnic identity that comes with making pots, even when there is no one left to make them for.

“Some here [in Rwanda] are herders,” she says, referring to the historical occupation of the Tutsi. “Some are farmers” – like the Hutu – “and some like us make pots.

“We will be potters even if we stop making pots – do you understand?” she says. “That is what we are. We will always be.”

The reporting of this story was made possible by a fellowship from the International Women’s Media Foundation (IWMF).