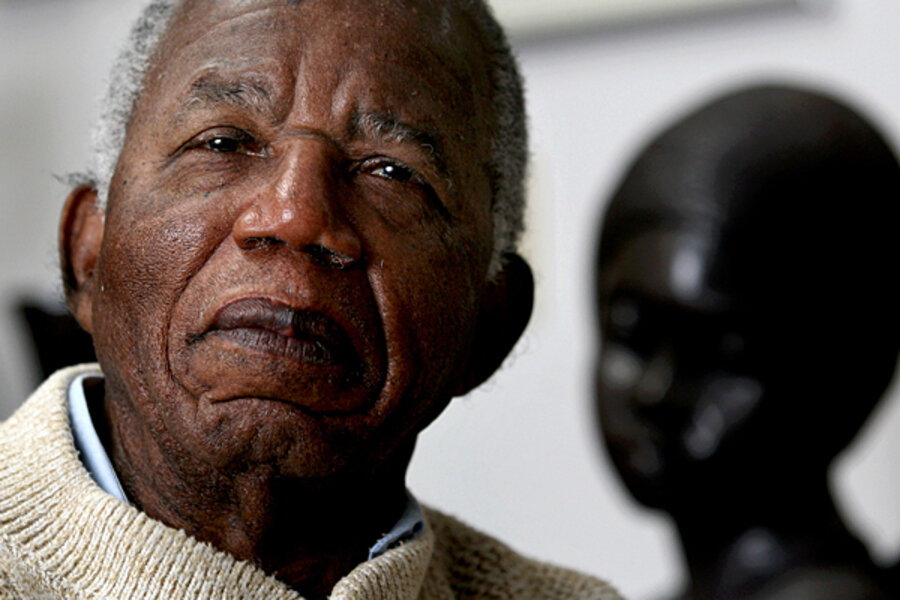

Famed author Chinua Achebe on the Occupy Nigeria strikes

Loading...

In an interview, Nigeria's premier novelist Chinua Achebe says that corruption is the root of the current fuel-strikes crisis, and that the only way to set Nigeria on a democratic path is for Nigerians to select better leaders, and to punish those who "steal from the state."

Professor Chinua Achebe currently teaches at Brown University as the David and Marianna Fisher University Professor and Professor of Africana Studies. He is the author of the globally acclaimed novels ''Things Fall Apart'', "A Man of the People",” Arrow of God" and "Anthills of the Savannah". He has also published collections of poetry, literary criticism and children's books. In 2007 he received the Man Booker international prize for his body of work from England, and more recently the 2010 Gish Prize. His new book a semi-autobiographical work called "There was a country: A personal history of Biafra" will be available from Penguin in September 2012.

Question: In your 1960 novel, "No Longer at Ease," you write about the coming problem of official corruption in Nigerian society, told through the rise and fall of your main character Obi. What do you think are the roots of corruption in Nigerian society – colonial legacy, corporate power, local business elites – and what will it take to uproot it?

Everything you mentioned has played a part. Nigeria has had a complicated colonial history. My work has examined that part of our story extensively. (No longer at ease, A man of the people and later Anthills of the savannah also tackle Nigeria’s burden of corruption and political ineptitude…) At this point in Nigeria’s history, however, we can no longer absolve ourselves of the responsibility for our present condition. Corruption is endemic because we have had a complete failure of leadership in Nigeria that has made corruption easy and profitable. It will be controlled when Nigerians put in place checks and balances that will make corruption “inconvenient” – with appropriate jail sentences and penalties to punish those that steal from the state.

The first republic produced political leaders in all the regions who were not perfect, but compared to those that came after them they now appear almost “saint like” – they were well educated, grounded politicians who may have embodied a flawed vision or outlook for the country (in my opinion); but at least had one.

Following a series of crises that culminated in the bloody Nigeria-Biafra war, Nigeria found itself in the hands of military officers with very little vision for the nation or understanding of the modern world. A period of great decline and decadence set in, and continues to this day. The civilian leadership of the Second Republic continued almost blindly the mistakes of their predecessors. At that point in our history, the scale of corruption and ineptitude had increased exponentially, fueled by the abundance of petro-dollars.

By the time the Third Republic arrived, we found ourselves in the grip of former military dictators turned ‘democrats’ with the same old mind set but now donning civilian clothes. So, Nigeria following the first republic has been ruled by the same cult of mediocrity – a deeply corrupt cabal – for at least forty years, recycling themselves in different guises and incarnations. They have then deeply corrupted the local business elites who are in turn often pawns of foreign business interests.

When I have talked about the need for a servant leader, I have emphasized an individual that is well prepared – educationally, morally and otherwise – who wants to serve (in the deepest definition of the word); someone who sees the ascendancy to leadership as an anointment by the people and holds the work to be highly important, if not sacred. I know that is asking for a lot, but that really should be our goal. If we aim for that, what we get may not be so bad after all.

That elusive great Nigerian leader that is able to transcend our handicaps – corruption, ethnic bigotry, the celebration of mediocrity, indiscipline etc- will only come when we make the process of electing leaders – through free and fair elections in a democracy – as flawless as possible, improving on each exercise as we evolve as a nation.

Once we have the right kinds of leaders in place – the true choices of the people – then, I believe, it will be possible to solidify all the freedoms we crave as a people- freedom of the press, assembly, expression etc. Within this democratic environment, the three tiers of government filled with servant leaders chosen by the people, can pass laws that will put in place checks and balances the nation desperately needs to curb corruption.

Question: During a 2006 trip to Nigeria, citizens told me that they welcomed the government's rhetoric about fighting corruption, but didn't place any faith in lasting change. Do you think a citizens' movement like Occupy Nigeria can be effective where official government efforts fail?

The right to protest, the right to freedom of assembly, freedom of association, and freedom of speech…these are all human rights that should be protected in any democracy, indeed in any nation. Any involvement of ordinary Nigerians in a non-violent (peaceful), organized, protest for their rights and improvement in their living standards, in my opinion, as a writer, should be encouraged. An artist, in my understanding of the word, should side with the people against the Emperor that oppresses his or her people.

The hope of course, is that the non-violent protest will eventually lead to change in a positive direction – like the civil rights movement in America, Mahatma Gandhi’s independence struggles in India etc. – if that is the case, then I am all for them.

A functioning, robust democracy requires a healthy educated, participatory followership, and an educated, morally grounded leadership. Civil society has a role to play in educating the masses about their rights – making sure that they understand that the elected officials report to them, that those in positions of leadership are not monarchs – and then insisting through the ballot box or other avenues of the democratic system that their voices be heard.

However, having said that, it is important to emphasize that Nigeria is a complicated country with more than 250 ethnic groups. Protests are often a symptom of deeper rooted problems – in Nigeria’s case, resistance to a fifty year history of leaders essentially swindling the nation of its resources – $400 billion worth - and stashing most of it abroad with little in terms of infrastructure on the ground. Nigeria continues to be held back by the lack of basic amenities – there is epileptic electricity supply (often times blackouts for months), very poor schools, no standard water supply systems, bad roads, poor sanitation…Nothing works – life, schools, electricity, nothing....

Question: The Arab uprisings in North Africa raised hopes that other authoritarian governments on the continent could also be challenged by citizen movements. Do you think the Occupy Nigeria movement has the potential to follow in the Tunisian and Tahrir Square footsteps?

Popular non-violent uprisings as an expression of the feelings of the people should be allowed and protected. I have already made that clear. The hope is that such movements coalesce onto a defined platform with a clear direction and leadership. The problem with leaderless uprisings taking over is that you don’t always know what you get at the other end. If you are not careful you could replace a bad government with one much worse! My hope for Nigeria actually is that the people will channel all that pent-up rage towards a fight for sound democratic institutions – a competent electoral body that can execute free and fair elections…in other words, exercise their frustrations at the ballot box. Movements that begin on the streets… on the ground… should channel their frustrations in a non-violent, organized direction – politically. But the great challenge for Nigeria – one that has stunted her development since independence – is how to convince 150 million people to put aside competing interests, sideline different religions, ethnicities, political persuasions, and build a united rostrum or two with strong leaders to truly bring about fundamental change to Nigeria. That is the challenge.

Question: The statement you signed supporting the Nigerian protests reads, in part, "The country's leadership should not view the incessant attacks as mere temporary misfortune with which the citizenry must learn to live; they are precursors to events that could destabilize the entire country." Nigerians in the past have seen themselves as complacent in fighting injustice. What makes this moment different?

Those that perceive Nigerians as complacent don’t completely understand our history.

Nigeria went through a thirty- month-long civil war that cost over 2 million lives (some say as many as three million); mainly children. After that, my people, the Igbo people, for whose survival the war was fought; were economically, politically, if not emotionally exhausted. The rest of Nigeria was also devastated, albeit, to a milder degree. Let us remember that at the time it was seen as one of the bloodiest wars in history. Following this catastrophe were several decades under the iron rule of Military dictators and civilian adventurers. A people don’t just jump up and protest after they have been nearly annihilated by war and then systematically subjugated for decades with their rights stripped from them for so long. In order to survive, people employ a number of tactics– they adopt a posture of subservience, quietness, etc., but it should never be interpreted as weakness. Human beings are alike everywhere you know. All human beings have their breaking point, it could be a big event or a small one; and for most long-suffering Nigerians the removal of oil subsidies made life intolerable because it exponentially increased the cost of living – food, transportation, education, water, you name it – over night. Most clear thinking bureaucrats should have seen this coming…as an untenable situation for the population.

Economists often give us condescending lessons in favor of fuel subsidy removal – that fuel subsidies siphon much needed cash away from the treasury of the federal government, that its removal will yield $8 billion; that those who benefit the most in the current system with subsidies are some of Nigeria’s wealthiest citizens; that subsidies further fuel corruption in the oil industry including the state-owned NNPC (Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation). Other reasons to take away subsidies this group also highlight include the fact that the presence of subsidies prolongs Nigeria’s dependence on fossil fuels, that they are indirectly implicated in the failure of Nigeria to establish and run refineries etc.

What has not been pulled into this entire debate is that the scale of corruption in Nigeria – the Nigerian government – and I am talking about corruption at all levels of government – Federal, state, local government, municipal, etc. – amounts to at least $10 billion a year ($400 billion in forty years). Putting an end to this should be the focus of the present government. Is this amount saved by tackling corruption in Nigeria not more than what would be made available with subsidy removal – and at no cost in pain and suffering to the average Nigeria?

If the present government reduced its own bloated budget, curbed the outrageous salaries and perks of parliamentarians, state governors, and local government officials - that would yield an additional hundreds of millions if not billions of dollars a year. And that at least would be a start. In an environment where corruption is truly tackled, a conversation can then be had with the people about a gradual withdrawal of subsidized petroleum products. But the way it was done, was harsh, even contemptuous of the average Nigeria and that is why it is being resisted.

Get daily or weekly updates from CSMonitor.com delivered to your inbox. Sign up today.